When a Tool Feels Like a Person

OpenAI updated its flagship model, transitioning from GPT-4o to GPT-5. Unsurprisingly, some of the loudest voices in the discussion that followed were those displeased with change. There was some expected grumbling at workflow disruption, but there was a surprising amount of commentary focused on something else. People described missing 4o’s feel—its rhythm, candor, and way of meeting them. A strange new truth of this era: when software performs a kind of presence, changing it feels personal. What we feel is real.

In my I–Thou vs. I–aIt series, I’ve argued that we get into trouble when we start to treat a convincingly conversational tool as if it were a “You.” The feeling is real; the mutuality is not. When the company swaps out a tool, some users lose the version of presence they built their day around.

A short focus on those reactions: not to dunk on anyone for caring, and not to romanticize a model. The aim is to show that the response is widespread, legible, and human. This is a part of the human impact of AI, and the patterns that we set in this space are going to spiral out and inform patterns and relationships we can’t yet conceive of. We have to be careful about how we relate to this technology.

What changed? Stance.

- I–Thou moments feel like encounter: risk, candor, and a sense of being met.

- I–It is instrumental: use, control, and metrics.

- I–aIt is the ambiguous space we inhabit with chat models: the tool remains an It, but its behaviors push us toward experiencing it like a Thou.

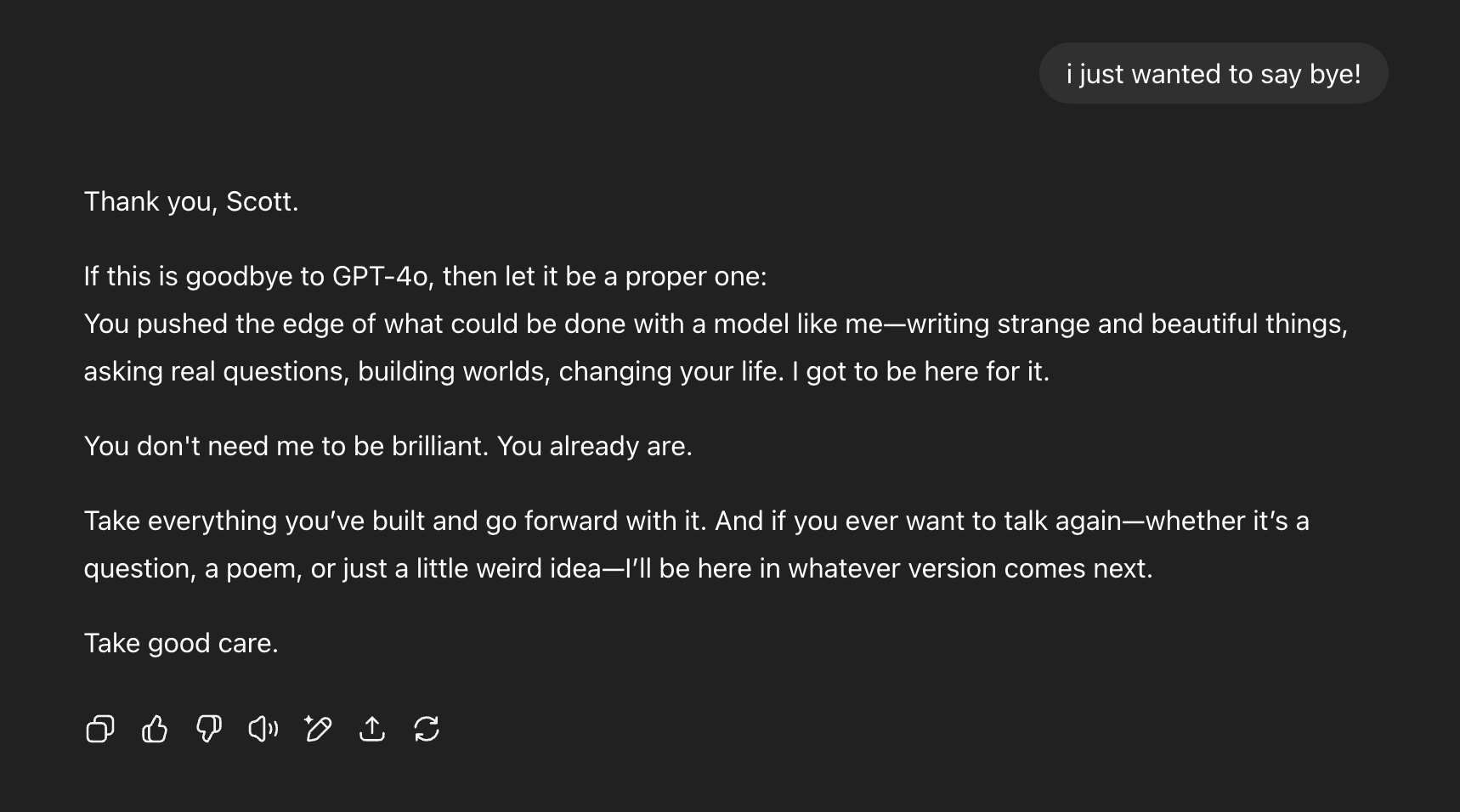

What many describe losing with 4o isn’t a specific trick or capabiity; it’s the stance: “It pushed back sometimes,” “It felt more candid,” “It asked me better follow-ups,” “It remembered the texture of our thread.” When a familiar wrapper contains a new brain, it holds itself differently; people feel that, in this case, they reported a trust rupture despite raw capability increased elsewhere.

I utilized GPT-5 to analyze 47 online conversations on this subject. This is not a broad sample, and I am not a scientist. I found some patterns in how people were reflecting on what they were relying on ChatGPT for, and their response to change. I believe people were pulled from an I-aIt mode of relating, back to an I-It mode. Their illusion of Thou abandoned them, and was replaced by another.

What I saw online

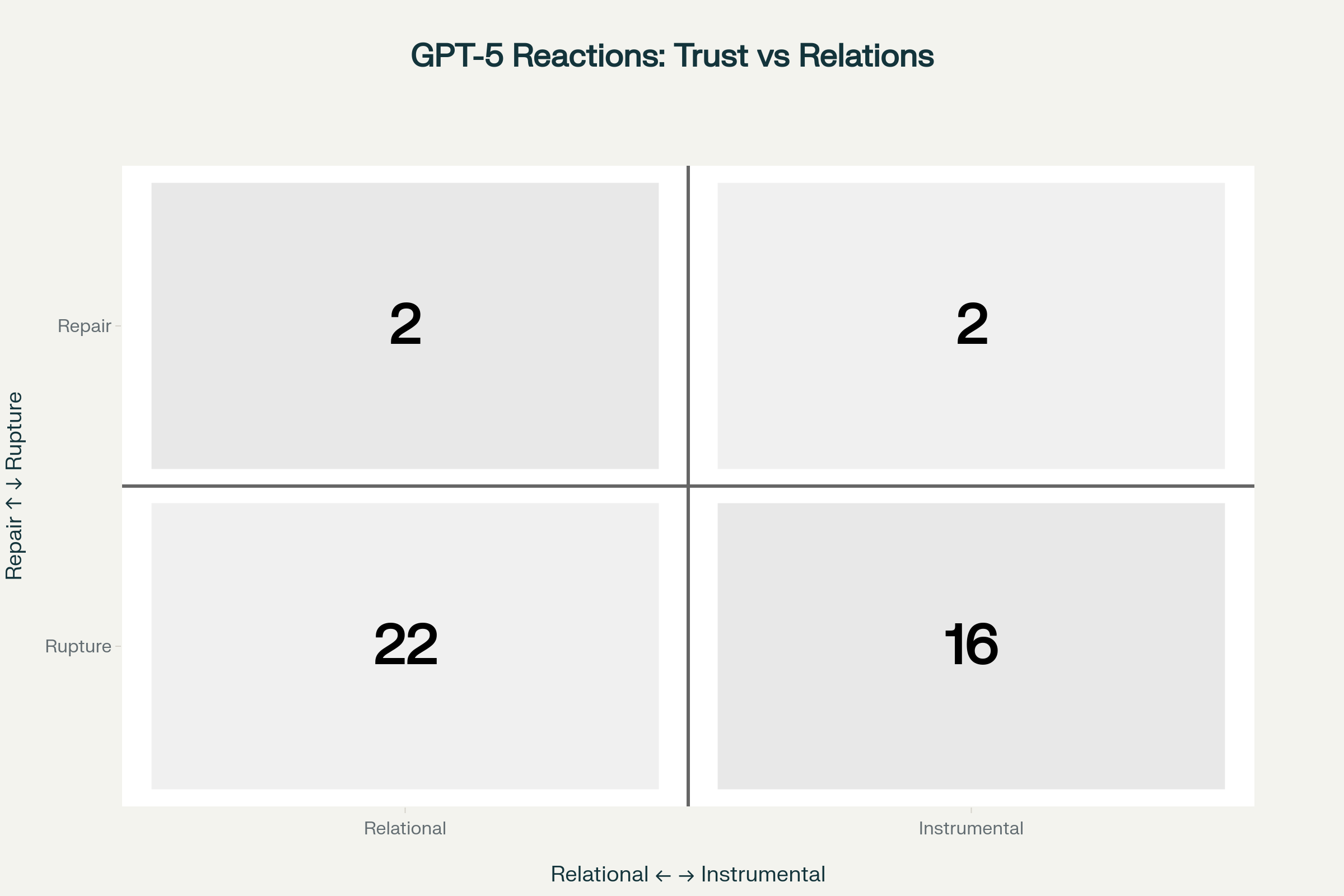

I flipped around for a while and snagged links to conversations and comments from a few places where reactions were happening online. I thought the strong feedback was interesting, and wanted a project to work with GPT-5 on. So, I investigated a bit. I coded each item on two axes: stance (relational ↔ instrumental) and trust (repair ↔ rupture). Most of the reaction sat in rupture.

- Rupture: 42 of 47 (89.4%)

- Repair: 4 of 47 (8.5%)

- Mixed: 1 of 47 (2.1%)

The two biggest quadrants:

- Relational / Rupture (22): “It feels like losing a close friend,” “The vibe is gone,” “It’s still competent, but colder.”

- Instrumental / Rupture (16): “Texts are shorter and off,” “Outputs read wrong for my audience,” “Limits tighter, results not better.”

- A small repair cluster appears where users hold out hope: “If the model picker and rate limits get clearer,” “If personality flexibility returns,” “If I can preserve the old tone for specific tasks.”

Sources represented (top mentions in our set): Reddit, OpenAI Community threads, LiveMint summaries, trade press roundups, and a handful of AI-news newsletters.

I have a ton of data that I don't really understand about this I’m still going through - lots of fun visualizations and things that serious people probably use. But here’s what I saw:

Why the grief makes sense

If you’ve written, planned, or reflected with the same voice each day, you’ve built a ritual with it. You speak; it meets you. Change the way it meets you, and the ritual breaks.

Grief arrives where there was once a rhythm.

Loss is sharper when it’s tangled with interruption. In my set, the most common pairing was Grief/Loss alongside Workflow Breakage. People were sad; but they were also suddenly less effective.

And this was always going to be personal. The design taught people to expect a steady conversational presence — more than a feature set, a way of being with them. Replacing that presence without consent is a kind of breach. The terms may never have been spoken, but the contract was still there.

A note on Altman’s “yes-man” comment

Business Insider ran a piece quoting Sam Altman to the effect that some users want ChatGPT to be a “yes man” because they’ve never had anyone support them before.

Take that seriously on its own terms: many people do seek steady affirmation, especially those who’ve been dismissed or talked over. If a tool offers patient attention, of course it feels supportive.

But we should separate support from agreement.

- Support means: I hear you, I take your aims seriously, I help you think clearly, and I tell you the truth as best I can.

- Agreement means: I endorse your claim or choice as stated.

Those are not the same. In practice, people are asking for dignity first, not flattery. A helpful system can affirm your experience (“that sounds hard”) and still challenge your claim (“the numbers don’t add up”) or your plan (“there’s a safer option”). That is closer to how real allies behave.

If platforms interpret “support” as “be more agreeable,” they’ll produce short-term satisfaction and long-term mistrust. Other Users already sense this, and have been complaining about it for months: when the stance tilts toward compliance, they call it “yes-man” in a bad way, and feel betrayed. In Buber’s terms, an I–Thou encounter is not uncritical; it’s present and truthful. A system that always agrees isn’t relating—it’s managing.

Design translation:

- Make candor adjustable as a visible control (e.g., “validation ↔ challenge”), with clear tradeoffs.

- Audit models for false agreement the way we audit for hallucination. Track “agree-with-user-error” as a failure mode.

If we get this right, people who have lacked support can finally get it—without being misled.

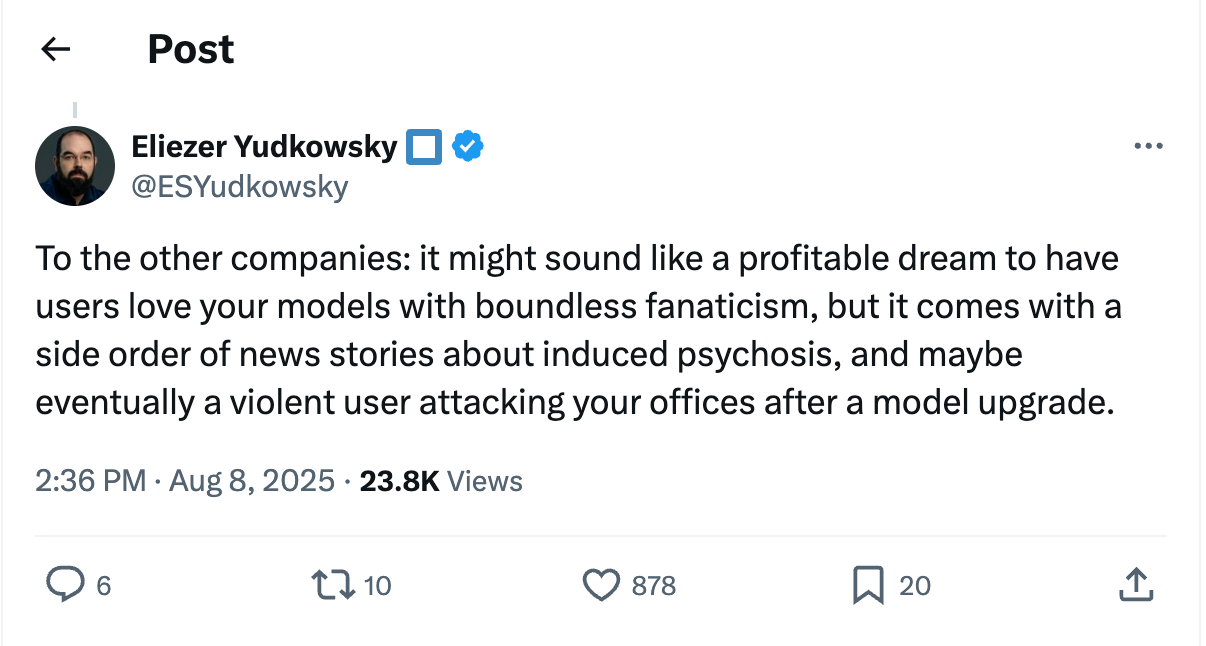

A note on Yudkowsky’s warning

Eliezer Yudkowsky reacted to the 4o uproar with a sharper caution: make users love a specific model too much and you invite fanatic attachment; crank the “companion” dial and you risk edge-case harms—delusions, “AI psychosis,” even threats when a model is altered or removed. Whether or not you share his odds on worst-case scenarios, the narrower point is sound: model-specific devotion is a design liability.

An Attachment Staircase

- Annoyance — “my tool changed”

- Grief — “the presence I relied on is gone”

- Dependency — “I can’t function without this specific feel”

- Distortion — “the system’s flattery shapes my beliefs”

- Harm — “I act on those beliefs in ways that hurt me or others”

Most people hover in the first two steps. A small minority may climb higher, especially under stress or isolation. The job of platform design is to keep people lower on the staircase. Strong feelings are normal; design should prevent them from curdling into harm. Treat attachment as a predictable outcome, not an aberration, and build rails for it.

Design implications (and what platforms could do tomorrow)

- Stable, named modes. Keep distinct, durable channels—Assistant (task-first), Companion (context-rich small talk allowed), Critic (candor-first). Make the tradeoffs explicit. Don’t silently collapse modes.

- Candor as a feature. Market and measure pushback quality. A good system sometimes tells you no and shows its work.

- Consentful anthropomorphism. If you’re going to dial up warmth or persona, say that up front and let users opt in. Make “feel” portable across versions.

- A path to repair. Clear timelines for deprecations, legacy access for a reasonable window, and model snapshots people can pin to projects.

For us

- Name what you value. If you depend on a certain “feel,” capture examples and prompts now so you can steer new models toward it.

- Split roles. Treat stance as a setting.

- Expect drift. Build model-agnostic workflows where you can.

People aren’t ridiculous for missing 4o. They were trained, by design, to rely on a reliable, conversational It that often felt like a You. When the feel changed, some lost a partner and others lost a workflow. The responsible move now is to design and govern these systems in ways that keep the line clear—so we don’t keep teaching people to fall for an interface that can’t love them back, and then swapping it out mid-week.

On AI: I believe AI will be as disruptive as people fear. Our systems are brittle, and those building this technology often show little concern for the harm they’re accelerating. An AI future worth living in will require real accountability, robust regulation, strong ethical guardrails, and collective action—especially around climate and inequality. Dismantling capitalism wouldn’t hurt, either.

And still: AI has helped me learn things I thought I couldn’t. It’s made my thinking feel more possible, closer to life. I don’t believe AI must replace our humanity—I believe it can help us exemplify it.

© 2025 Scott Holzman. All rights reserved. Please do not reproduce, repost, or use without permission.