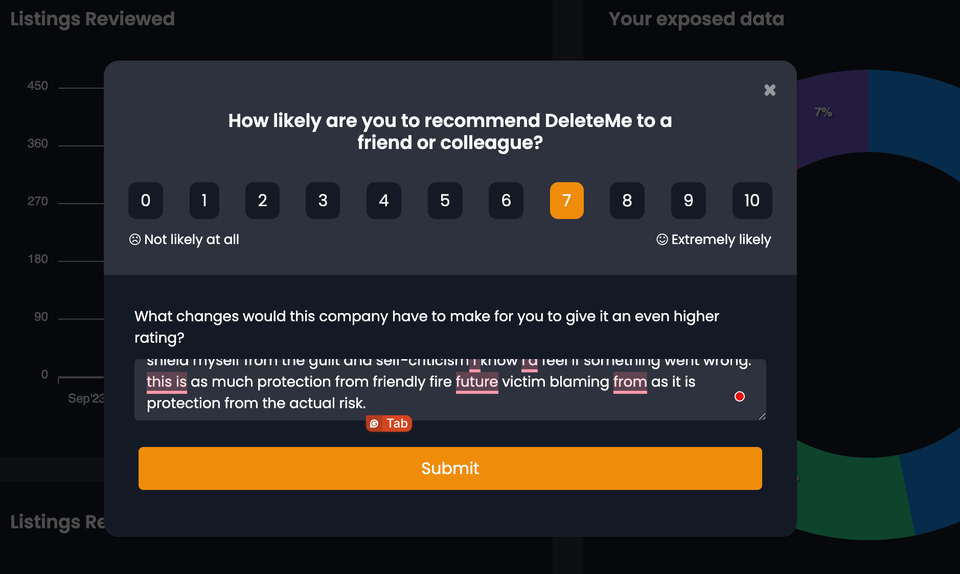

What changes would this company have to make for you to give it an even higher rating?

i feel safer, and a sense of relief. but i don't know how to explain it well enough that i'd feel comfortable telling a friend that i spent money on this service, or that i think they should too. i feel a sense of security, like if my identity gets stolen or w/e that now i wont feel like it was my fault for not doing more to prevent it. i think i bought this to shield myself from the guilt and self-criticism i know i’d feel if something went wrong. this is as much protection from friendly fire future victim blaming from as it is protection from the actual risk.

here is the safety and there is the worry and i pay for the safety so that i do not sit with the worry or i sit with a different worry or the worry sits differently it sits beside me or behind me and not on top not crushing only humming i do not want to be the kind of person who says i should have done more i should have known more i should have stopped it i think about the future and the blame and the blame is a kind of weather and i am building a shelter i am buying a little blanket a thin blanket not a wall but a soft something for the cold that comes from what if from how could you let this happen and i say to myself you have done enough or maybe not or maybe it is only weather

the hum is a churning hum

the churn is a humming churn

Know ye, now, Bulkington? Glimpses do ye seem to see of that mortally intolerable truth; that all deep, earnest thinking is but the intrepid effort of the soul to keep the open independence of her sea; while the wildest winds of heaven and earth conspire to cast her on the treacherous, slavish shore?

—Herman Melville, Moby-Dick, Chapter 23, “The Lee Shore” (1851)

of course, it does have its risks. I quote verbatim from Wikipedia, bolding for emphasis:

Traditional rules for survival cannibalism among sailors

This specific custom, also known as "the delicate question" or "the proper tradition of the sea", specified that in case of disaster, when there was not enough food for the survivors, corpses could be eaten. If "there were no bodies available for consumption, lots were drawn to determine who would be sacrificed to provide food for the others". As long as the lottery was fair, giving everyone an equal risk of dying to become food for others, this was considered "entirely legal" and justified by the circumstances. "On the whole, sailors and the general public knew and accepted [this] protocol of cannibalism to survive ship disasters."

The historian A. W. Brian Simpson observed:

If properly conducted, cannibalism was legitimated by a custom of the sea; and the popular literature, augmented by the unrecorded tales seamen told each other, ensured that there was general understanding of what had to be done on these occasions and that survivors who had followed the custom could have a certain professional pride in a job well done; there was nothing to hide.

Referring to William Arens' widely-read book The Man-Eating Myth, he added that, since "maritime survival cannibalism, preceded by the drawing of lots and killing, was a socially accepted practice among seamen until the end of the days of sail ... it is ... not an exception but a counterexample" to Arens' thesis "that cannibalism, as a socially accepted practice, is a myth".

The only cases when cannibalism in maritime disasters sometimes led to legal prosecution was "when the lotteries were fixed or absent altogether", in violation of the accepted custom. Such violations were nevertheless common enough. Captains and other crew members were often unwilling to put their own lives at risk, as the rules of the custom demanded, instead choosing to sacrifice those they considered "more expendable ... (such as slaves, young boys, and passengers)" to serve as food for the other survivors.

Consuming the Dead: A Brief Cultural History of Funerary Cannibalism

On grief, ritual, and the strange continuity of the body

Across time and geography, humans have developed a wide variety of customs for honoring the dead. Burial, cremation, mummification, exposure, and water burial are some of the most common ways different societies have tended to their dead. One of the least common—and most misunderstood—is funerary cannibalism, also known as endocannibalism: the practice of consuming the body of a person after their death, typically by members of their own community.

This was not a widespread global norm, but neither was it an aberration limited to a single place or era. In multiple regions—particularly parts of South America, Melanesia, and South Asia—funerary cannibalism was practiced as a meaningful and sometimes sacred act. While it is almost uniformly treated with horror in modern Western contexts, it served important social, spiritual, and emotional functions for the people who practiced it.

Documented Practices

South America

In the forests of Amazonia, funerary cannibalism was practiced among several Indigenous groups well into the 20th century.

- Among the Wari’ of what is now western Brazil, the bodies of deceased family members were roasted and consumed by relatives as part of communal mourning. Anthropologists describe this as an act of compassion, intended to honor the deceased and help their spirit transition[1]. Aparecida Vilaça, who spent decades studying Wari’ cosmology, emphasizes that the Wari’ concept of “body” (kwere-) is not a fixed anatomical structure, but a relational substance shaped through proximity and kinship. “All who live together are consubstantial,” she writes; “the Wari’ mean ‘we, people, human beings,’ and is defined in opposition to game animals”[2].

- The Yanomami, living along the border of Brazil and Venezuela, cremated their dead and consumed the bone ash, often mixed into plantain soup or fermented drink. This was seen as a way to keep the deceased within the family[3].

- The Ache (Guayaki) of Paraguay were observed in the 1960s to consume the remains of deceased relatives in specific mourning rituals[4].

These traditions varied in form but all shared an intention of reverent incorporation, rather than desecration or violence. Vilaça adds that these rituals also served to reclassify the dead: “The ingestion of the body dehumanizes the dead, situating them in the position of prey, differentiating them from the living who, as predators, are perceived as human”[5].

Melanesia

The Fore people of Papua New Guinea practiced funerary cannibalism until the mid-20th century. Women and children consumed the bodies of deceased relatives, believing this would free the dead person’s spirit and keep it from lingering[6].

This practice led to the spread of kuru, a prion disease transmitted through brain tissue. Once the connection was understood, the practice ceased. The last known kuru victim died in 2009[7].

Other groups in the region, such as some in Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands, also practiced ritual cannibalism of the dead, though often less extensively documented.

South and Central Asia

The 5th-century BCE Greek historian Herodotus reported that the Callatiae, a people of India, practiced funerary cannibalism and were horrified by Greek cremation customs[8].

He also described the Issedones, in Central Asia, who were said to eat their dead elderly in funeral feasts, preserving their skulls as gilded relics[9]. These reports are ancient and filtered through Greek worldviews, but they echo practices found elsewhere.

In the 19th century, Betsileo elders of Madagascar explained a now-lost tradition in similar terms: “They had been told by their ancestors that … in absorbing the physical substance of the deceased, they also absorbed his spirit. In this way, the family unit and its qualities remained the same”[10].

Cannibalism Accusations: Colonialism’s Justification

European colonial powers often spun lurid tales of cannibalism to paint Indigenous peoples as less human than white europeans—and thereby excuse their most brutal campaigns of conquest. By portraying a target population as man-eaters, colonizers created a moral panic that portrayed enslavement, land theft, and even genocide not only acceptable but righteous. From the Americas to Africa and the Pacific, some of the worst atrocities of empire were justified as crusades to stamp out cannibalism.

The Americas: “Just Wars” on Cannibals

One of the earliest and most documented examples comes from the Caribbean. Christopher Columbus and his successors described certain Native peoples (the so-called “Caribs”) as cannibals to legitimize enslaving them.[11] In 1503, Queen Isabella of Spain even decreed that Indigenous subjects were not to be enslaved—except those accused of cannibalism.[12] This loophole virtually invited Spanish colonists to brand tribes as cannibals and wage war. Columbus himself exploited this narrative:

“These things could be paid for in slaves taken from among these cannibals… they will be finer than any other slaves once they are freed from their inhumanity, which they will lose as soon as they leave their own lands.”[13]

Congo Free State: “Civilizing” by Carnage

Cannibalism tales persisted into the era of the "Scramble for Africa," not just a race for territory—it was a wave of violence, extraction, and domination unleashed upon the African people by European powers. In the Congo Free State under King Leopold II (1885–1908), Belgian authorities claimed to be uplifting Central Africans from barbarism—cannibalism included.[14] In practice, Leopold’s regime perpetrated acts of extreme genocidal violence. Ironically, the colonial forces themselves condoned cannibalism when it suited them. The Force Publique (Leopold’s army) recruited some tribal fighters with cannibalistic rituals, and officials often turned a blind eye as these allies ate the flesh of defeated enemies.[15] After one rebellion in the 1890s, a young Belgian officer coolly described his troops’ grisly post-massacre feast as “horrible but exceedingly useful and hygienic.”[16] Leopold’s propagandists in Europe touted how his rule was ending “savage” customs—one 1914 postcard bragged of progress “from cannibalism to civilisation” in the Congo.[17] Meanwhile, millions of Congolese died from forced labor, executions, and famine. Labeling the Congolese as sub-human “cannibals” deflected blame and cast the slaughter as part of a benevolent white mission.[18]

Pacific Islands: Myths of the “Cannibal Isles”

Across the Pacific, colonial powers likewise wielded cannibalism narratives as a tool of domination. In Fiji British colonizers and missionaries pointed to instances of Fijian cannibalism as a “moral imperative justifying colonisation.”[19] Europeans derided many local customs as “debased,” convincing themselves that Fiji was “a paradise wasted on savage cannibals.”[20] By sensationalizing such practices (indeed present, though not as widespread as claimed),[21] they rationalized their annexation of Fiji in 1874 as an act of humanity and order. Similar rhetoric followed Captain Cook and other explorers to places like New Guinea and the Marquesas—reports of cannibal feasts, whether real or exaggerated, stirred horror back home and helped justify violent “pacification” of island populations.

In sum, accusations of cannibalism became a horrific propaganda weapon in the colonial arsenal. These stories reduced Indigenous peoples to monsters in the European imagination, making extremes of cruelty appear as regrettable but necessary civilization work. Whether in the Congo, the Americas, or the Pacific, the cannibal trope provided a gruesome alibi for genocide—one that, tragically, cloaked conquest in a veneer of moral duty even as it destroyed whole cultures and societies. The historical record lays bare this pattern, urging us to confront how false narratives are and were used to justify indefensible violence.[22]

A European Detour: Medical Cannibalism

Though Western Europe has no known tradition of funerary cannibalism, it does have a long and mostly forgotten history of corpse consumption in the name of medicine.

From the 16th through 18th centuries, European apothecaries sold powdered human remains as remedies. Mumia, a powder made from human remains stolen from ancient Egyptian tombs, was used to treat internal bleeding and bruises[23]. When imported mummies ran short, local corpses were sometimes substituted.

Human blood was believed to carry vitality and was consumed fresh from executions, particularly by those seeking to cure epilepsy[24]. Human fat was rendered from corpses and used in ointments. In Germany, a tonic called blood marmalade mixed human blood with wine and herbs.

These practices were mainstream. Royalty, clergy, and physicians participated in them. They were not framed as cannibalism but as medical science.

The contradiction is worth noting: while Indigenous funerary rites were vilified as barbaric, Europeans were quietly ingesting corpses themselves.

This is not an endorsement of funerary cannibalism.

I couldn’t think of anything more universally vilified in our current cultural context than eating people. So I wanted to learn about the people who did—or still do—and try to understand their thinking. What I wound up learning was how righteously our prejudice and greed can initialize our judgment of the humanness of the other.

Researching this reinforced for me how strange and wide the human story is. There are so many ways to grieve, honor, hold on, and let go. There are so many ways to make sense of life. I tried to approach this from a place of dignity.

I used AI tools, including GPT4.0, 4.1, 4.5, DeepResearch, and Claude 3.5 Sonnet, to assist in researching and writing this whatever it is. I did my best to check my facts. I'm just a guy. Let me know if something feels fishy.

Notes

- Beth A. Conklin, Consuming Grief: Compassionate Cannibalism in an Amazonian Society (University of Texas Press, 2001). ↩︎

- Aparecida Vilaça, Strange Enemies: Indigenous Imaginaries and the Making of Modern Brazil (Duke University Press, 2010), p. 61. ↩︎

- Napoleon Chagnon, Yanomamö: The Fierce People (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, multiple editions). ↩︎

- Pierre Clastres, Chronicle of the Guayaki Indians (Zone Books, 1998). ↩︎

- Aparecida Vilaça, Comendo como Gente: Forma e Perspectiva entre os Wari’ (UFMG Press, 2002), p. 185. ↩︎

- Shirley Lindenbaum, “Understanding Kuru: The Contribution of Anthropology and Medicine,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 2008. ↩︎

- Rae Ellen Bichell, “The Last Laugh: The Story of Kuru,” NPR, April 2016. ↩︎

- Herodotus, Histories, Book 3.38. ↩︎

- Herodotus, Histories, Book 4.26. ↩︎

- Maurice Bloch, From Blessing to Violence: History and Ideology in the Circumcision Ritual of the Merina of Madagascar (Cambridge University Press, 1986), p. 131. ↩︎

- Hulme, Peter. Colonial Encounters: Europe and the Native Caribbean, 1492–1797. Routledge, 1992, pp. 84–86.

- Queen Isabella of Castile, “Decree Concerning the Indians,” 1503; see translation in Anthony Pagden, The Fall of Natural Man (Cambridge University Press, 1982), p. 136.

- Christopher Columbus, Letter to Ferdinand and Isabella, 1503, in Select Letters of Christopher Columbus, translated by R.H. Major, Hakluyt Society, 1847, p. 140.

- Hochschild, Adam. King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. Houghton Mifflin, 1998, pp. 119–122.

- Ibid., pp. 124–125.

- Ibid., p. 124. See also Louis-François de Magnin, Les Grandes Chasses du Congo, 1899.

- Stengers, Jean. Congo: Mythes et réalités, Editions Racine, 2005, p. 212.

- Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost, pp. 233–237.

- Thomas, Nicholas. Colonialism’s Culture: Anthropology, Travel and Government. Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 125.

- Ibid., p. 126.

- Sissons, Jeffrey. “Fiji’s Colonial Experience: A Study of the Impact of British Colonial Rule on Fijian Society,” in The Journal of Pacific History, Vol. 14, No. 1 (1979), pp. 48–51.

- Arens, The Man-Eating Myth, pp. 156–158.

- Richard Sugg, Mummies, Cannibals and Vampires: The History of Corpse Medicine from the Renaissance to the Victorians (Routledge, 2011). ↩︎

- Louise Noble, Medicinal Cannibalism in Early Modern English Literature and Culture (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011). ↩︎

© 2025 Scott Holzman. All rights reserved. Please do not reproduce, repost, or use without permission.