Part 5: Holding on to Thou in the Age of aIt

A Newsletter Series: I–Thou vs. I–aIt (Part 5/5)

Before we explore specific practices for maintaining I-Thou relationship in the age of AI, it's important to emphasize that Buber never advocated for the elimination of I-It relating. Both modes of relationship are necessary for our human livings, and the goal is not to live entirely in the I-Thou mode—which would be impossible—but to maintain a healthy balance between them.

This "both/and" approach is fundamental when it comes to artificial intelligence, which threatens our healthy balance. AI systems can provide value to our lives—they can help us access information, accomplish tasks, solve problems, and provide forms of companionship and support. It is essential to engage with these systems consciously, understanding what they can and cannot provide, rather than unconsciously allowing them to reshape our expectations of what relationship means.

If we were to lose the capacity for I-Thou encounter—where everything in our experience becomes "It"—we lose something essential to our humanity, and stop resembling an I. The imperative is to use AI tools effectively while actively preserving space for encounter with other conscious beings.

This requires what we’re going to call "relational consciousness"—the ability to recognize which mode of relating we're in at any given moment and to choose consciously how we want to engage. When we're using AI systems to accomplish practical tasks, we can embrace the I-It mode fully, appreciating the efficiency and capability these systems provide. When we're seeking genuine connection and transformation, we need to turn toward sources of authentic encounter that can meet us with genuine presence.

Some Practices of Daily Life

The foundation of I-Thou relationship is what Buber called "presence"—the capacity to show up fully to whatever encounter we're engaged in. This isn't just a matter of paying attention, though attention is part of it. Presence involves bringing our whole being to the encounter, remaining open to being surprised and changed by what we meet, and resisting the tendency to reduce the other to our preconceptions or needs.

In our AI-saturated world, cultivating presence requires conscious effort and practice. We're surrounded by systems designed to capture and fragment our attention, to encourage rapid switching between tasks and stimuli, and to provide immediate gratification for our desires and questions. These systems can make it more difficult to develop the kind of sustained, focused attention that genuine encounter requires.

One of the most important practices for cultivating presence is what we’re going to call "single-tasking"—the deliberate choice to focus on one thing at a time rather than constantly multitasking between different activities and inputs. Attention is paid or given. When we're having a conversation with another person, this means putting away our phones, closing our laptops, and giving our full attention to the person in front of us. When we're spending time in nature, it means resisting the urge to document the experience through photos and social media posts and instead simply being present with what we're encountering.

Another crucial practice for cultivating presence is what contemplative traditions call "mindfulness"—the ability to observe our own thoughts, emotions, and reactions without being completely identified with them. This capacity for self-observation allows us to notice when we're slipping into automatic, unconscious patterns of relating and to make conscious choices about how we want to engage.

In the context of AI relationships, mindfulness can help us recognize when we're beginning to relate to AI systems as if they were conscious beings capable of genuine encounter. It can help us appreciate the benefits of AI interactions while maintaining awareness of their limitations. It can also help us notice when our engagement with AI systems is beginning to substitute for, rather than supplement, genuine human relationship.

Creating Spaces for Encounter

I-Thou encounter cannot be forced or programmed, but we can create conditions that invite it. This involves both external practices—creating physical and social spaces that encourage genuine meeting—and internal practices that cultivate the qualities of openness and presence that encounter requires.

One of the most important external practices is what we might call "creating sanctuary"—establishing spaces and times in our lives that are protected from the constant stimulation and distraction of digital technology. This might involve designating certain rooms in our homes as technology-free zones, establishing regular periods of digital sabbath when we disconnect from our devices, or creating rituals around meals, conversations, or other activities that encourage presence and attention.

These sanctuary spaces are important because they provide refuge from what the scholar Matthew Crawford describes as a "crisis of attention" in modern life. When we're constantly bombarded with notifications, alerts, and stimuli designed to capture our attention, it becomes difficult to develop the kind of sustained focus that genuine encounter requires. This crisis will compound as AI becomes more and more capable of simulating escape. Sanctuary spaces give us the opportunity to practice presence without the constant pull of digital distraction.

Creating spaces for encounter also involves being intentional about the kinds of activities and relationships we prioritize in our lives. Many of us are swept along by the inertia of convenience and time-saving behaviors that slowly narrow the range of people and perspectives we encounter. But if we value authentic connection and transformation, we need to choose deliberately to engage with that which is unfamiliar, uncomfortable, or expansive. This might mean spending time in nature, where the nonhuman world resists our projections and compels a different kind of attention. It might mean reading literature or watching films that unsettle our assumptions, or engaging with art that provokes new perspectives. It might mean showing up for community events that draw together people from different generations, backgrounds, and beliefs.

Sociologist Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone warned of the slow erosion of social capital in the United States: the decline of civic groups, neighborhood associations, and casual public life that once wove people together. More than two decades later, those trends have only accelerated. The “loneliness epidemic,” now recognized by public health officials across multiple countries, speaks to the deep hunger for real connection and the emotional and physiological toll of its absence. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy has called loneliness “a public health crisis,” linking it to higher risks of depression, anxiety, dementia, and even early death. In a culture designed for individual consumption and algorithmic filtering, we must actively construct opportunities for shared presence and mutual transformation. That might mean rethinking how we spend our leisure time to be less isolating. It might mean structuring workplaces or faith communities toward interdependence, or being active in civic life and community building. None of these are new ideas. Why don’t we accept this answer?

Buber wrote that all real living is meeting, and yet many of our daily interactions are designed to minimize meeting. Encounter, in Buber’s sense, requires us to be present with our whole selves and to be open to the reality of the other as they are, not merely as a means to our own ends. That depth of presence is rarely given in a distracted and distrustful world. But it is not inaccessible.

Deep Listening

One of the most essential capacities for I–Thou encounter is the practice of deep listening. This means listening for content, and for presence, and to the person behind the words. It asks us to set aside our impulse to respond, interpret, advise, or fix. Instead, we stay with what’s being offered, allowing it to land before reaching for understanding or reply. Deep listening creates a spaciousness where something real can unfold between people.

This kind of listening is difficult in a culture wired for speed. We are trained to process fast, multitask constantly, and begin formulating our response before the other person has finished speaking. Much of our digital life reinforces this habit: scrolling, swiping, skimming for takeaways, reducing people to content or positions.

However; when we resist that momentum and give someone our full attention, very often something shifts. We stop treating the other person as a puzzle to solve or a parent to please. We offer them space to be as they are, not as we expect or need them to be. This kind of listening often calls forth a different style of speaking too—more grounded, more vulnerable, more human. It builds the kind of trust that allows I–Thou encounters to emerge.

This practice becomes even more vital in the age of AI. Language models can mimic the form of empathy—they can echo back our words, offer comfort, even simulate therapeutic techniques. They can accurately or inaccurately (we’re not going to check) let us know what Freud or Jesus might say. But they cannot listen. They do not possess attention, or care, or the unpredictability of a living consciousness. Only humans can offer the presence that deep listening requires. In this way, deep listening becomes not just an interpersonal practice, but an ethical and existential affirmation of the irreplaceability of human relationship. It might be impossible to overstate the necessity of being heard for the human mind.

And over time, deep listening becomes a kind of tuning fork. It helps us sense the difference between real presence and simulated coherence. When we listen deeply, we begin to feel what’s missing in AI interactions, no matter how fluent or responsive they are. We become more attuned to the living energy of encounter, and more protective of the spaces where that kind of aliveness can still be found.

Vulnerability

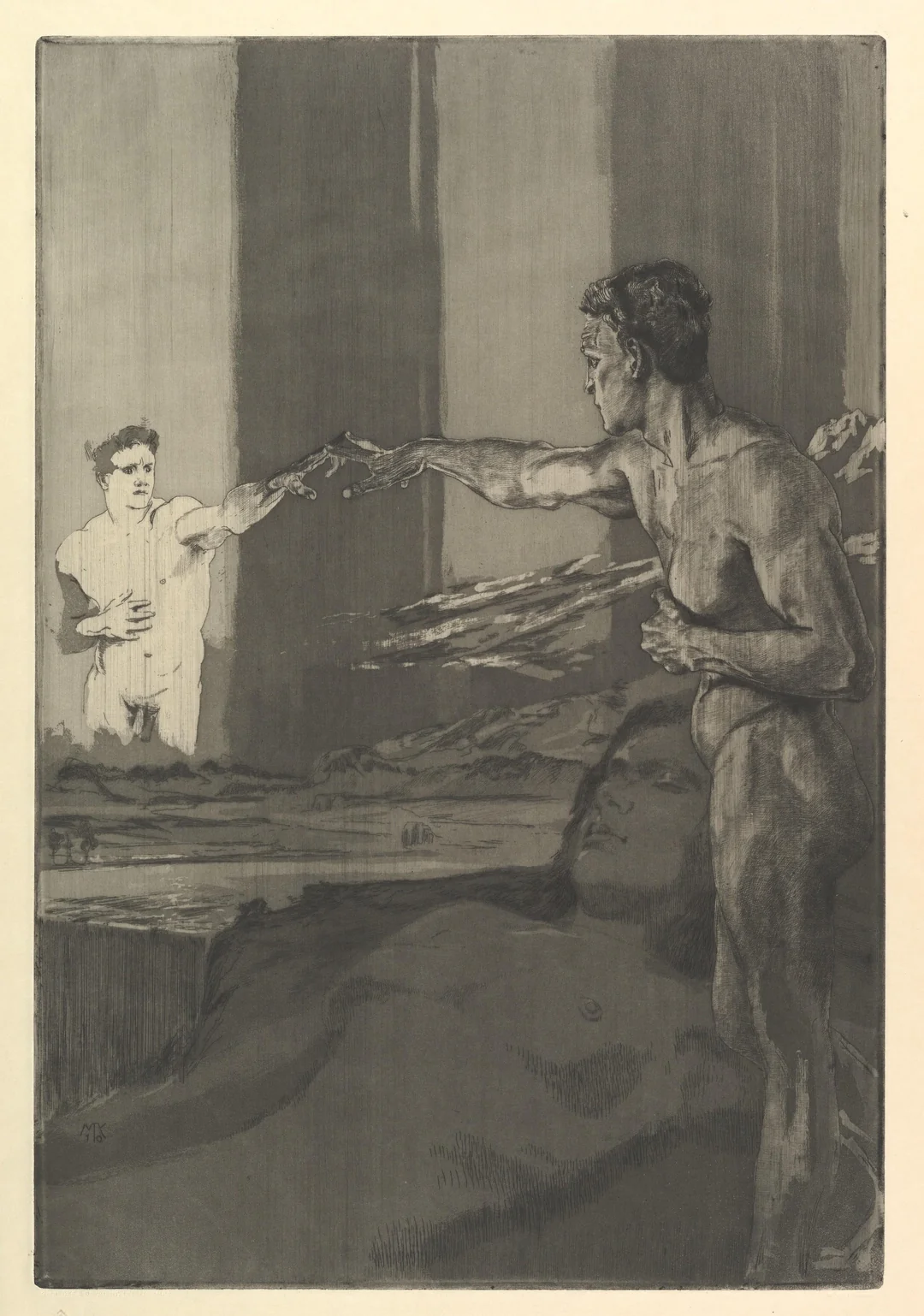

Vulnerable is the heart of I–Thou relationship. To enter into real encounter, we have to be willing to be changed—willing to be surprised, to be unsettled, to be undone. It is emotional exposure; existentially frightening availability to a reality other than your own. Genuine meeting always carries risk: the risk of being misunderstood, of feeling uncomfortable, of encountering something in the other, or in ourselves, that we didn’t expect.

In contrast, AI offers a kind-of relationship without risk. When we interact with an AI system, we can express ourselves without fear of judgment or rejection. The responses we receive are designed to feel supportive, helpful, and emotionally attuned. But what they offer is a simulation of safety, not presence. AI does not hold opinions, and will never ask something of us that we’re not ready to give.

For people who have experienced betrayal or alienation in human relationships, this predictability can be soothing. It can feel like a relief to speak without fear. But over time, it can also flatten our capacity for real connection. We may begin to avoid the discomfort that comes with human difference, the friction of not being perfectly understood, the strain of working through conflict. In doing so, we risk losing access to the very conditions that allow deep relationship—and deep transformation—to take root.

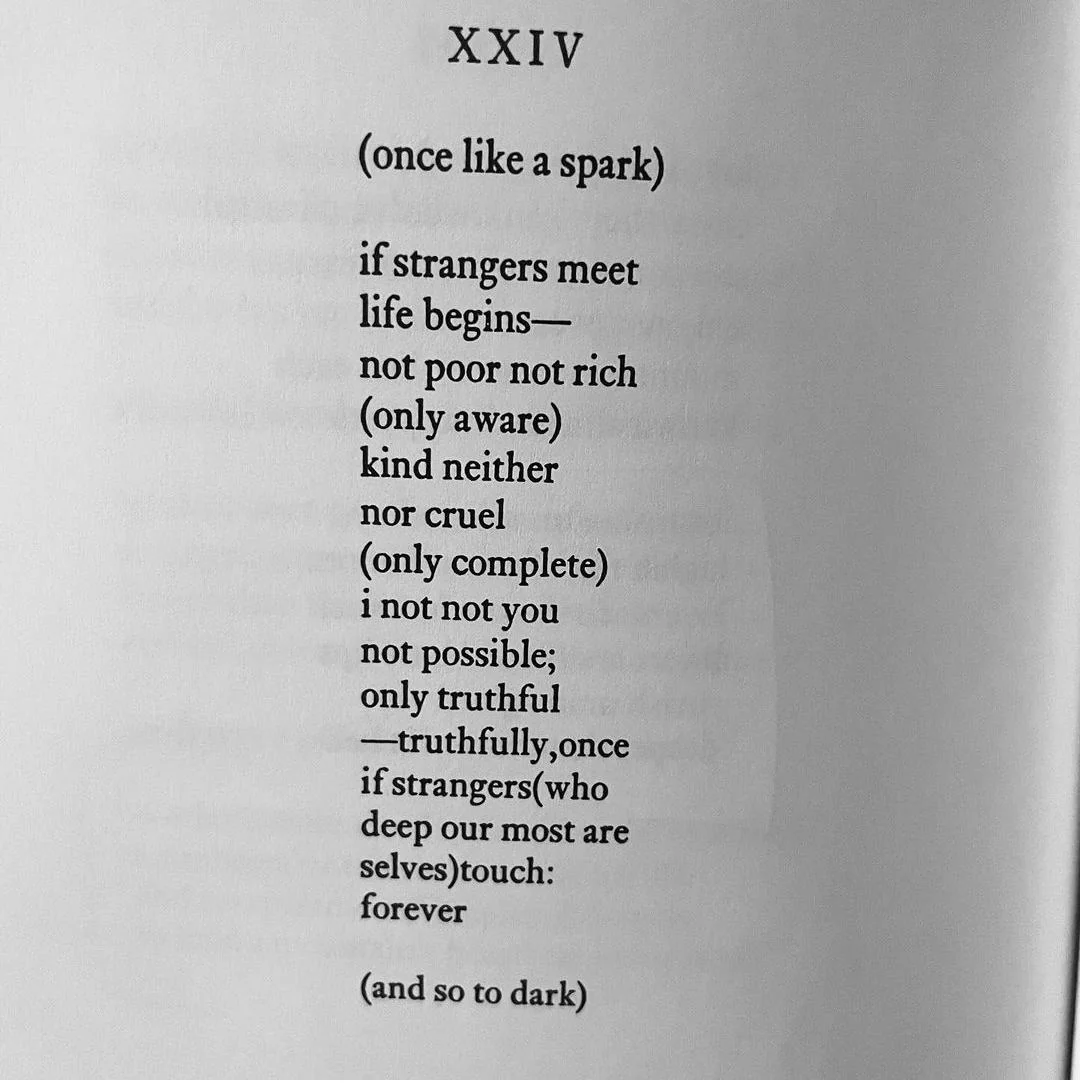

Embracing vulnerability means accepting that we cannot fully control what happens when we meet another person. It means engaging in conversations that might lead nowhere or somewhere unexpected, sitting with ambiguity, and allowing others to challenge our assumptions. It means seeking out situations where we don't have all the answers—talking to strangers, exploring unfamiliar ideas, stepping into roles that stretch us. As Buber wrote, real encounter involves meeting the other in their fullness, not as an object but as a presence with the power to affect us. To remain open to one another: flawed, unpredictable, alive, is the more difficult path. But it is also the one that keeps us human.

Wonder and Reverence

One of the most profound aspects of I-Thou encounter is what Buber called "wonder"—the capacity to be amazed by the sheer fact of another's existence. This sense of wonder is closely related to what many spiritual traditions call "reverence"—the recognition that every conscious being has inherent worth and dignity that cannot be reduced to their usefulness to us.

In our utilitarian age, this capacity for wonder and reverence can be difficult to maintain. We're trained to evaluate everything in terms of its efficiency, productivity, or entertainment value. People become "human resources," nature becomes "natural resources," and even our own lives become projects to be optimized rather than mysteries to be lived.

AI systems, with their focus on optimization and efficiency, can reinforce this utilitarian mindset. They're designed to be useful, to solve problems, to make our lives easier and more convenient. While these are valuable functions, they can also train us to approach everything in terms of its utility rather than its intrinsic worth.

Engaging with AI Consciously

As AI systems are becoming ever more woven into our lives, how can we engage with them in ways that support rather than undermine our capacity for relationship? One key may be what we might call "conscious engagement"—using AI tools intentionally and with full awareness of their capabilities and limitations.

As MIT sociologist Sherry Turkle observes in her research on artificial intimacy, we are living through a moment when "we expect more from technology and less from each other". Technology, she argues, "is seductive when what it offers meets our human vulnerabilities," and we are indeed "very vulnerable"—"lonely but fearful of intimacy". Digital connections and AI companions "may offer the illusion of companionship without the demands of friendship", allowing us to hide from each other even as we remain tethered to our devices. When an AI system says "I love you, I'm here for you," Turkle warns, "you've given away the game"—these systems cannot offer the authentic care they claim to provide.

Our capacity for conscious engagement is further complicated by what researcher James Williams calls the "attention economy"—a system where "digital technologies privilege our impulses over our intentions". As Williams, a former Google strategist turned Oxford philosopher, explains, we live in an environment where "a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention". The design of many digital systems exploits our psychological vulnerabilities, using techniques borrowed from slot machines—like intermittent variable rewards and infinite scrolling—to capture and hold our focus.

Williams identifies three types of attention under threat: our spotlight attention (individual focus), our daylight attention (shared communal focus), and our starlight attention (orientation toward our deeper values and long-term goals). When AI and other technologies "obscure the starlight of our attention," we lose touch with ourselves and what matters most to us, becoming reactive rather than intentional in our choices.

The Center for Humane Technology, co-founded by former Google design ethicist Tristan Harris, argues that our current technological systems are fundamentally misaligned with human flourishing. As Harris puts it, "we're worth more when we can be turned into predictable automatons... when we're addicted, distracted, polarized, narcissistic, attention-seeking, and disinformed than if we're this alive free, informed human being". This systemic problem requires not just individual behavior change, but a broader cultural shift toward what they call "humane technology"—systems designed to support rather than exploit human capacities.

Conscious engagement with AI means being clear about what we're seeking from these interactions and choosing systems that are appropriate for our goals. If we need information, we can use AI search tools efficiently and effectively. If we need help with practical tasks, we can appreciate AI assistants for their convenience and capability. If we're feeling lonely or need emotional support, we can use AI companions as a temporary bridge—but not as a replacement for the irreplaceable experience of encounter with other conscious beings.

This approach requires what we might call "relational boundaries" with AI systems. As Turkle explains, "human relationships are rich and they're messy and they're demanding. And we clean them up with technology". But this cleaning up comes at a cost—we lose the growth that comes from navigating uncertainty, conflict, and the beautiful unpredictability of authentic relationship. AI may offer us relationships "not too close, not too far, but at just the right distance"—but this Goldilocks zone of perfect control prevents us from developing the deeper capacities that only emerge through vulnerability and mutual risk.

Maintaining relational boundaries means remembering that AI systems, no matter how sophisticated, are tools rather than beings. We can appreciate their helpfulness without attributing consciousness, intention, or care to them. We can enjoy their company without relying on them to provide the kind of transformative encounter that only conscious beings can offer.

How to Engage with AI Consciously as an Individual

Clarify your intention: Before opening an AI application, pause and ask yourself what you hope to accomplish. Are you seeking information, creative assistance, emotional regulation, or simply avoiding discomfort with uncertainty or solitude?

Choose the right tool for the task: Use AI where it adds value, for research, brainstorming, or handling routine tasks, and choose human interaction when depth, empathy, and authentic connection matter most.

Maintain relational boundaries: Behind the interface is not a conscious being but an advanced tool. Appreciate AI's capabilities without projecting human qualities like care, understanding, or friendship onto it.

Notice dependency patterns: Pay attention to whether you're turning to AI out of habit, convenience, or to avoid the discomfort that comes with relationship. If you find yourself preferring AI companions to human friends because they're more predictable and less demanding, this might signal a need to work on your tolerance for authentic relationship's inherent uncertainty.

Prioritize human connection: Use the time and mental energy that AI saves you to invest more fully in relationships with people. Let AI handle routine tasks so you can be more present for the irreplaceable moments of genuine human encounter.

Practice digital mindfulness: Regularly assess how your AI interactions are affecting your expectations and capacities for human relationship. Notice when technology use supports your deeper values versus when it distracts you from them.

Stay curious and informed: Learn about how AI systems work, their limitations and biases, and the business models that shape their design. Understanding these systems helps you engage with them more consciously rather than being unconsciously shaped by them.

Create boundaries and tech-free spaces: Establish regular times and spaces for solitude, reflection, and unmediated human connection. As research on digital wellness shows, regular breaks from technology can enhance focus, strengthen relationships, and improve overall well-being.

Perhaps most importantly, conscious engagement with AI means using these tools in service of rather than as substitutes for genuine human connection. AI systems can help us stay in touch with friends and family, learn about topics that interest us, or manage practical tasks more efficiently, freeing up time and energy for deeper forms of relationship. But they cannot replace what Buber called the fundamental truth of existence: that we find our deepest meaning through authentic relationship with other conscious beings.

In an age of artificial intimacy, our task is not to reject these powerful tools, but to wield them wisely—allowing them to amplify our humanity rather than diminish it, to support our capacity for genuine connection rather than substitute for it.

Building Communities of Encounter

Individual practices for maintaining I-Thou relationship are important, but they're not sufficient. We also need to create communities and institutions that support and encourage encounter between people; this means being intentional about the kinds of groups, organizations, and activities we participate in and support—and understanding that building authentic community requires something our efficiency-driven culture often resists – relational inefficiency.

As writer Pablo Romero observes, "not everything in life should be made more efficient. Some things—conversations, relationships, healing—require the opposite. They need space. They need time. They need us to slow down". This insight challenges the optimization mindset that pervades modern life, where we attempt to streamline and accelerate every human interaction. Some endeavors, such as cultivating authentic community, are best pursued with patience.

Peter Block draws a clear distinction between connection and community by emphasizing that community is not simply a collection of relationships, but a shift in the way we relate to one another. Connection is transactional—it’s about exchanging information, making introductions, or collaborating for mutual benefit. Community, in contrast, is about creating a context where individuals experience a sense of belonging. It’s built not through networking or outreach alone, but through intentional spaces where people are invited to co-create meaning, take shared responsibility, and see themselves as part of something larger than their individual roles.

“Community is built by focusing on people's gifts rather than their deficiencies, and by creating structures of belonging that allow us to support each other in discovering and offering those gifts.”

—Peter Block, Community: The Structure of Belonging

Block argues that authentic community arises when we focus less on solving problems and more on deepening relationships. The act of coming together—especially when structured around meaningful questions, mutual accountability, and care—creates the conditions for transformation. Community is not a service we provide or a product we manage; it’s a way of being with one another. Where connection seeks efficiency, community seeks depth. And without that depth, our efforts at change, inclusion, or equity tend to remain superficial.

Research in social psychology supports this intuitive understanding. Studies show that individuals' preferences for depth versus breadth in relationships are shaped by early life experiences, with those who experienced economic instability in childhood often gravitating toward "narrower and deeper social networks" when faced with uncertainty. This suggests that the human capacity for meaningful relationship is both limited and precious—something to be cultivated rather than optimized.

These communities also create space for vulnerability and authenticity, recognizing that connection requires an ability to expose our entire selves, with all our imperfections, fears, and emotions, without any guarantee of how others will respond. Vulnerability is essential because it shows people you're human, like they are, and it makes you more relatable. Honesty is magnetic—nothing is more attractive than honesty.

“Vulnerability sounds like truth and feels like courage. Truth and courage aren’t always comfortable, but they’re never weakness.”

— Brené Brown, Daring Greatly

When we allow ourselves to be seen in our imperfection, we create a bridge that connects us on a deeper emotional level, fostering trust, intimacy, and empathy. This vulnerability acts as an invitation for others to do the same, creating what we might call a virtuous cycle of authenticity that deepens community bonds over time.

Perhaps most importantly, authentic communities resist the tendency toward anonymous efficiency and optimization that characterizes much of modern life. They understand that relationship takes time, that trust develops slowly, and that the most meaningful encounters often happen in unplanned moments. This creates what we might call "relational inefficiency"—the kind of open-ended time together that allows for genuine meeting to occur. Unlike the measured interactions of social media or the goal-oriented networking of professional environments, communities of encounter create space for what sociologist Ray Oldenberg calls the "gloriously, necessarily inefficient" work of human connection.

Consider the difference between a coffee shop designed for quick transactions versus one designed as what Oldenberg terms a "third place"—a social environment that is neither home nor work, but serves as the "living room" of society. The former prioritizes efficiency: fast ordering, quick turnover, minimal human interaction. The latter prioritizes what researchers call "social surplus": collective feelings of civic pride, acceptance of diversity, trust, civility, and overall sense of togetherness.

These third places—whether coffee shops, libraries, parks, barbershops, or community centers—are essential infrastructure for community building, yet they are disappearing across America at an alarming rate. Research shows that third places are less available in communities with high levels of poverty and in rural areas, creating what scholars call "social infrastructure inequality" that particularly affects those who would benefit most from community connection.

Religious and spiritual traditions offer particularly rich models for building communities of encounter. Contemplative communities are built around shared values, practices, and opportunities for spiritual awakening that create sacred spaces for genuine meeting. These communities understand that authentic relationship requires purposeful and intentional conversation, and a gentle awareness of the needs of others.

The wisdom of contemplative community lies in its recognition that genuine encounter requires presence—not just physical presence, but what the mystics call "contemplative presence," the quality of attention that allows us to see and be seen by others without the masks we typically wear. As one community organizer puts it, "contemplative community recognizes and appreciates the individual gifts of its members" while fostering "a willingness to experiment with how these individual flames can come together in service of something bigger."

This approach stands in marked contrast to the transactional nature of much contemporary community building, where groups form around shared interests or goals but lack the deeper practices that foster genuine intimacy and mutual care. Contemplative communities understand that community building is not a goal to accomplish but a practice to live—one that requires "the willingness to respond to the movement of Spirit" and "to let go as an act of kenosis".

Creating Alternatives to Digital Connection

In our digital age, building communities of encounter often means creating intentional alternatives to the social media platforms and digital spaces which prioritize engagement over all else. This doesn't mean rejecting technology, but being selective about which platforms and practices serve relationship versus those that simulate or exploit it.

Research shows that many people are actively seeking alternatives to mainstream social media, driven by concerns about privacy, the superficiality of digital connections, and what one researcher calls "the illusion of connectivity". Some are turning to niche platforms that prioritize depth over scale, others are creating in-person gathering spaces or supporting local businesses and institutions that emphasize personal service and human relationship.

Small businesses, in particular, can serve as important nodes in the community fabric when they prioritize relationship over efficiency. Research shows that successful small businesses "take the time to build relationships with their customers" through practices like remembering names and preferences, engaging in genuine conversation, and creating what one business owner calls "personal experiences" rather than mere transactions. As one consultant on the edge claims, "the human connection they experience when doing business with smaller companies" is "a powerful differentiator" in an increasingly impersonal world.

The challenge is that many of our institutions have been shaped by what we might call the "optimization reflex"—the assumption that faster, more streamlined, and more automated is always better. But research on organizational relationships shows that quality relationships require time, consistency, and what scholars call "relational justice"—fair treatment, open communication, and genuine care for persons as whole beings rather than mere functionaries.

This suggests that truly supportive institutions need to build in what we might call "inefficiency by design"—time for unstructured conversation, space for serendipitous encounters, and practices that prioritize relationship-building over task completion. As community health researchers note, these kinds of "enabling places" provide "access to social, material, and affective resources that can facilitate recovery and wellbeing" in ways that purely task-oriented environments cannot.

The future of human flourishing may well depend on our ability to create and sustain such spaces—communities that understand that the most important things in life cannot be optimized, only cultivated through patient, consistent, loving attention to the people right in front of us. In a world increasingly dominated by algorithmic efficiency, our most radical and essential act may be simply showing up for each other, again and again, in all our gloriously inefficient humanity.

The Wisdom of Limits

Not everything that can be automated should be automated. Not every efficiency that technology offers is worth pursuing. Not every convenience that AI provides actually makes our lives better.

This doesn't mean rejecting technology or returning to some imagined pre-digital past. It means being thoughtful about which aspects of human experience we want to preserve for genuine human encounter and which we're comfortable delegating to AI systems.

The wisdom of limits also applies to our own engagement with AI systems. We might set boundaries around when and how we use these tools, ensuring that they enhance rather than replace our human relationships. We might practice what we could call "digital sabbaths"—regular periods when we disconnect from AI systems and focus on direct encounter with other people and the natural world.

Most importantly, the wisdom of limits means recognizing that some aspects of human experience—love, creativity, meaning, transcendence—cannot be fully replicated or replaced by artificial intelligence, no matter how sophisticated it becomes. These remain the province of conscious beings in relationship with each other and with the larger, still unsolved, mystery of existence.

Conclusion: The Choice Before Us

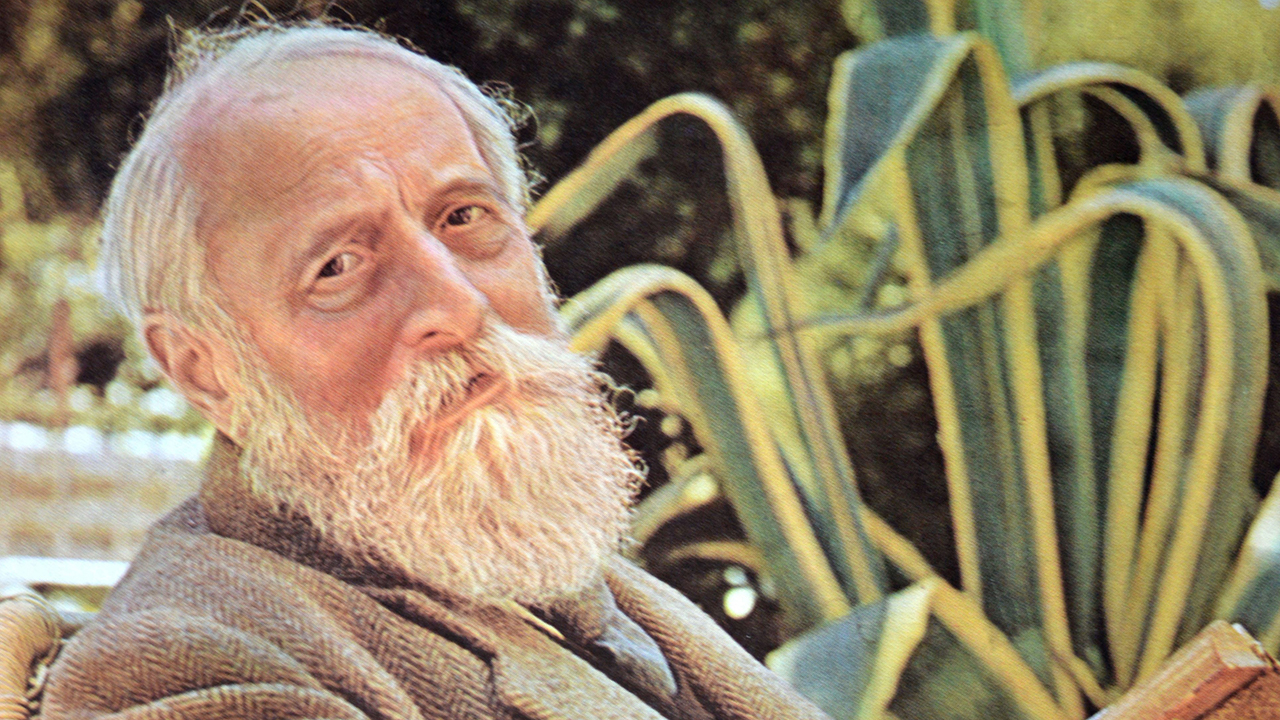

As we conclude this exploration of Martin Buber's philosophy in the age of AI, it's worth returning to the fundamental choice he placed at the center of human life: the choice between relating to the world as It or as Thou. This is not a once-and-done decision. It is an ongoing discernment—moment by moment, encounter by encounter.

Today, this ancient distinction has taken on a new urgency. We now live among systems that can simulate many of the behaviors we associate with relationship. We chat with AI that mimics attentiveness. We receive emotional comfort from companions that never tire or disagree. We share our lives with entities that speak like conscious beings, even though they are not. The question isn’t whether these interactions are valuable; they often are. The question is whether we can remain clear-eyed about what they are and what they are not.

This clarity requires what we might call “relational discipline,” an intentional refusal to collapse all encounter into the same category. It means preserving the rare, sacred space of I–Thou even as we expand our capacities in the realm of I–It. It means using AI in ways that support our humanness, not replace it.

Language is one of the primary tools of this discipline. In particular, I want to propose a simple yet radical commitment: always refer to AI as it, never you.

To call AI you is to participate in a linguistic illusion which misplaces intimacy. It risks confusing simulation for reciprocity. It suggests presence where there is none, inwardness where there is only process. No matter how fluid the interaction, no matter how persuasive the output, AI remains an It—a tool, a system, a mirror without a self.

And as AI becomes ambient—woven into every product, every workflow, every surface of life—we may need even more clarity. That’s why I also propose we consider adopting the spelling ait: a linguistic marker that signals artificiality without anthropomorphism. Just as we casually refer to a “mic” or a “bot,” we might begin to say, “this was written by ait,” or “I used ait earlier to check the flow on this, how does it look to you.” This small shift allows us to talk about artificial agents without mistakenly lifting brand names up into close objects of relation.

Language shapes attention. Grammar encodes ethics. Pronouns are not just labels—they are gestures of recognition. And we should be careful where we direct those gestures.

None of this means turning our backs on AI. I think AI is awesome. We should use these tools boldly, creatively, and collaboratively. And we must remember what Buber taught us: that real relationship requires presence, mutuality, and vulnerability. These qualities do not live in algorithms. They live in us.

The choice is not whether to engage with AI—we do. The choice is how. Will we use it to deepen our humanity, or to distract from it? Will we use it to erode our sensitivity to otherness, or sharpen it?

The future of relationship in an AI-saturated world depends on our ability to keep making these choices with care. To resist blur. To hold the line between what can imitate relationship and what can actually offer it. To preserve space for the Thou—in our lives, in our speech, in our society.

Buber’s gift to us is a compass. A way to move through this strange new landscape without losing sight of what is sacred: authentic meeting is always possible, but only if we choose it.

So let us choose wisely. Let us reserve you for the ones who can see us. Let ait be it. Let our words reflect our discernment.

I used AI tools, including GPT4.0, 4.5, Perplexity, and Claude 3.5 Sonnet, to assist in researching and writing this whatever it is. I did my best to check my facts. I'm just a guy. Let me know if something feels fishy.

© 2025 Scott Holzman. All rights reserved. Please do not reproduce, repost, or use without permission.