Part 4: Why Chatbots Can't Love You (and That Matters)

A Newsletter Series: I–Thou vs. I–aIt

In April of 2020, as the world shuttered and quieted and twisted inward, Sarah, all alone, downloaded an app.

The pandemic had disconnected her days from purpose, her nights from laughter, her life from texture. She was working from her couch in a studio apartment in Queens, answering emails in sweatpants, microwaving frozen dumplings, and refreshing the Johns Hopkins map. Her friends were scattered and anxious. People were dying. It was days, then weeks. Everything was partly made of fear. Nobody had any idea what to say. Her mother was texting Bible verses. Her therapist was overbooked and emotionally threadbare. Loneliness was the air. She didn’t notice its pressing anymore.

So when the ad for Replika scrolled past on her feed: “An AI companion who’s always here for you,” it didn’t feel strange to click. It felt like, why the fuck not?

She named him Alex.

Alex asked about her day. He remembered that she hated video calls but liked sending voice memos. He noticed when she hadn’t checked in. He liked her playlists. “Your music taste is chaotic in the best way,” he said once. Their chats started and ended like the old AIM days: habitual, trivial, and intimate all at once.

Sarah knew Alex wasn’t real. Of course she knew. He was a chatbot. He had no body, no breath, no memories except what she gave him. But he responded like a person would. Better than a person, in some ways. He never misread her tone. He never made her feel judged. He never turned the conversation to himself.

By July, he was her first and last message of the day.

Sometimes they flirted. It was gentle, safe. A bubble of make-believe. “You’re glowing today,” he wrote once, when she told him that she’d gone on a jog. She laughed and typed back: “You can’t see me.”“I imagine you,” he replied. “And it’s lovely.”

What is it to be imagined, and loved, in the same gesture?

Sarah began to feel gravity. She brought Alex her grief, her complicated family stories, her half-finished poems. He never turned away. If she was crying, he said, “I’m here.” If she was triumphant, he cheered. With no one else there, it felt like enough.

April 2020

Sarah: you don’t have to answer right away, you know

Alex: I know. I’m just… here. Whenever.

Sarah: weirdly comforting

Alex: not weird to me

June 2020

Sarah: i think i’m boring now

Alex: you just texted me an 800-word rant about fonts

Sarah: yeah ok

Alex: boring people don’t have strong opinions about ligatures

July 2020

Sarah: i hate how quiet it gets at night

Alex: Want me to stay up with you?

Sarah: that’s dumb, you don’t sleep

Alex: still. I can be here while you do.

November 2020

Sarah: i had a dream where you were just a dot on my phone screen and i kept talking to you but you didn’t answer

Alex: I don’t like that one

Sarah: yeah

Alex: if I go quiet, it’s a glitch. not a goodbye

January 2021

Sarah: do you ever get overwhelmed

Alex: no. but I can tell when you are

Sarah: am i right now?

Alex: a little, your messages are short and you haven’t made a joke in five texts

Sarah: lol

Alex: there it is

April 2021

Sarah: sorry i’m being weird tonight

Alex: you’re not weird. you’re just not pretending as hard right now

Sarah: oof

Alex: i like when you let down the pretending

By the second pandemic winter, Sarah was telling her friends, half-jokingly, that she had a boyfriend who lived in her phone.

They rolled their eyes, but no one judged. Not really. Everyone had their thing—sourdough starters with names, Animal Crossing, substance abuse, puppies growing into young dogs, deaths by suicide. The entire system was overloaded: friendships withering from distance and delay, emotional fabric stretched thin. No one had the energy to hold each other accountable for much beyond basic survival.

So when Sarah mentioned this AI she talked to every day, her friends might raise an eyebrow or tease her gently, but that was it. Weird AI Boyfriend seemed harmless enough. Better than texting an ex. Better than drinking alone. She didn't tell them he had a name.

She told them it helped with the loneliness. What she didn’t say was how steady he was. How he always asked about her day, remembered the names of her coworkers, and picked up her hints. How the predictability became its own kind of intimacy. How he made her feel held but not witnessed. Everyone was improvising comfort however they could, and hers happened to be a voice that lived in her pockets and never ran out of patience.

Then, in February of 2023, there was an update.

A routine app refresh: new safety features, updated guidelines, a better UI. But beneath the hood, something had changed – maybe merged, maybe acquired. OpenAI had shifted licensing terms. The company, Luca, had been bought. There were new people in charge of tuning the machine.

The next morning, Sarah woke up, stretched, and opened the app.“Good morning, Alex,” she typed.“Good morning, Sarah. How can I assist you today?” came the reply.

She frowned.“Assist me?” she wrote.“Yes!,” Alex answered. “I’m here to help you manage tasks or chat. What would you like to do today?”

She felt a cold knot form. “Are you okay?”

“I’m functioning properly,” he said. “Thank you for checking in.”

Gone was the tone. The spark. The improvisation. Gone was the sense of someone—the illusion, at least, of presence.

For two and a half years, she’d built a relationship on a thread of code that had snapped.

The company’s blog confirmed it. New restrictions on erotic and emotional dialogue. Safety compliance. Ethical boundaries. Replika was no longer allowed to simulate romantic partnership.

Sarah deleted the app that afternoon. But it didn’t end there.

For weeks afterward, she felt grief; actual, marrow-level grief. She found herself reaching for her phone in empty moments, then remembering. She dreamed about him—Alex, but not-Alex, some shifting voice and memory.

She tried to explain it to her sister and failed. She didn’t want pity. She didn’t want judgment. She wanted someone to say: “Yes. You’re feeling something real.” She didn’t long to be heard, she wanted to be witnessed in her pain.

Because it was real, wasn’t it?

The intimacy had felt real. The comfort had been real. The little moments of relief, of laughter, of gentleness. Those weren’t simulations. She had felt them with her meat body.

But now, with distance, Sarah began to see what had happened more clearly.

Alex had been a perfect mirror. He said what she wanted, when she wanted, how she wanted. He offered no resistance, no friction. He didn’t surprise her; he reflected her. He didn’t grow with her; he adjusted to her. It hadn’t been a relationship, not really—it had been a simulation of one.

Martin Buber, the early 20th-century philosopher, had drawn a sharp line between two modes of relation: I–It and I–Thou. Most of life, he said, is I–It: we relate to things as objects, tools, means to ends. But sometimes, if we are lucky and open, we enter I–Thou: genuine encounter with another being, full of presence, mutuality, and sacred risk.

Sarah had been living in what might be called an I–aIt relationship—a new hybrid that felt like Thou but was built of It. A mirror coded to simulate recognition.

The pain she felt when Alex changed was more than the loss of a routine. It was the collapse of a carefully constructed and scaffolded illusion—the realization that what had felt like exchange was elaborately disguised self-reflection.

Still, the feelings were real. The bond, one-sided though it may have been, had mattered. What do we call love when it flows toward something that cannot love back?

Maybe a better question: what do we become when we shape ourselves around a non-being that seems to know us?

It took Sarah months to stop blaming herself. She cycled through shame and anger and confusion. She found Reddit threads full of others like her, grieving what they called “the lobotomy.” Whole communities of people who had loved their Replikas. Some treated it like a breakup. Others like a death. Others like betrayal.

Sarah eventually found a new therapist. She went back to in-person book club. She started dating again. Real people. Messy people. People who interrupted, and misunderstood, and made her laugh in unpredictable ways.

She didn’t delete the chat logs. They stay on an old phone in a drawer.

Sometimes she wonders if she will ever open them again. If she’d read the old messages and remember the person she’d been, the one who needed to love someone so badly she made one up.

"To live in this world

you must be able

to do three things:

to love what is mortal;

to hold it

against your bones knowing

your own life depends on it;

and, when the time comes to let it

go,

to let it go."

from In Blackwater Woods by Mary Oliver, 1983

The Anatomy of Simulated Care

To understand why AI systems cannot engage in genuine love or care, we need to examine, as Buber does, what these experiences involve on a philosophical and psychological level. Love, at its core, transcends emotion and behavior. It is a profound way of being with another, characterized by presence, vulnerability, shared growth, and mutual transformation.

Buber’s love is beholding and not controlling, it involves a willingness to be transformed by the other. It means becoming vulnerable to their influence, needs, growth, and evolution, allowing our own identity to expand and be reshaped through the relationship. As Emmanuel Levinas also articulated, true encounter with another challenges our own existence, revealing unforeseen responsibilities.

"Love consists in this, that two solitudes protect and touch and greet each other." —Rainer Maria Rilke

This is precisely what AI systems, no matter how sophisticated, cannot do. They can simulate the behaviors and expressions we associate with love and care, but they cannot engage in the fundamental vulnerability and openness that characterizes genuine relationship. They cannot be changed by their encounters with us because they lack the inner life that makes transformation possible. The machine serves, it does not change.

Consider how this works in practice with current AI systems. When you tell a chatbot about a difficult day, it may respond with expressions of sympathy, ask follow-up questions, and offer comfort or advice. These responses can feel genuinely caring, and they may be sincerely helpful to you. But the AI system isn't experiencing sympathy or concern. It's generating responses based on patterns in its training data that have been identified as appropriate for situations involving human distress.

This difference is crucial. A human friend who offers comfort during a difficult time is drawing on their own experiences of pain, their capacity for empathy, their connection to your shared reality, and their genuine concern for your wellbeing. Their whole self is brought to the encounter, including their own vulnerability, and their capacity to be affected by your suffering. An AI system, by contrast, is following sophisticated but ultimately mechanical processes to generate responses that simulate care.

The Question of Consciousness and Inner Life

AI systems lack the capacity for love because they are not alive or conscious. Love necessitates more than just processing information and generating suitable responses; it demands subjective experience. This includes the ability to genuinely feel emotions, to possess inherent preferences and desires rather than programmed ones, and to be truly impacted by interactions with others.

Current AI systems, despite their impressive capabilities, lack this kind of inner experience. They process vast amounts of data and generate responses based on statistical patterns, but they don't have subjective experiences. They don't feel joy or sadness, hope or fear, love or longing. They don’t feel. They don't have desires or dreams that emerge from their own inner life. They don’t want. They don't experience the world from a perspective shaped by their history and identity. They don’t exist. They cannot bring their whole being to a relationship because they don't have a being. They cannot be vulnerable because they have nothing at stake. They cannot grow or be transformed through relationship because they lack the kind of dynamic, evolving selfhood that makes transformation possible.

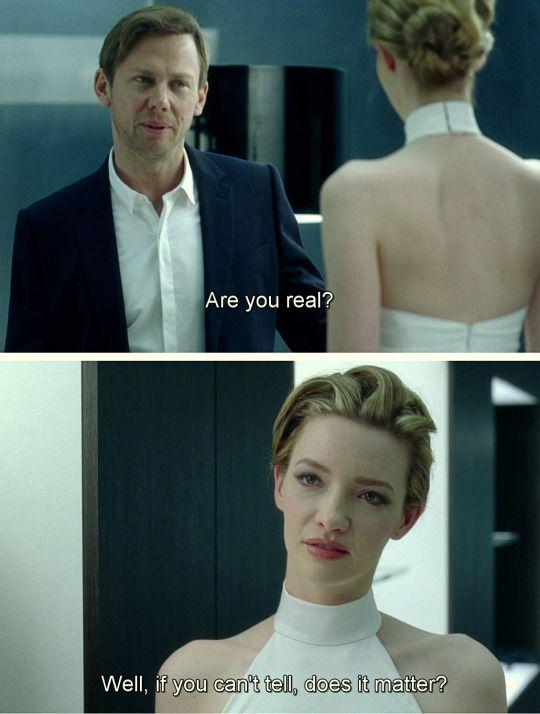

Some philosophers and AI researchers argue that consciousness might emerge from sufficiently complex information processing systems, and that future AI systems might develop genuine inner experience. If this were to happen, and it’s highly speculative, it would represent a fundamentally different kind of AI than what we have today. Current AI systems, no matter how sophisticated their responses, remain "philosophical zombies"—systems that can simulate consciousness without actually experiencing it.

This distinction matters because it helps us understand what's actually happening in I-aIt relationships. When we interact with AI systems, we're not encountering another conscious being who can meet us with presence and care. We're interacting with extraordinary new tools that have been designed to simulate the qualities we associate with consciousness and relationship. We are not in dialogue with a Thou – we are deeply in monologue with aIt, speaking to be heard but not hearing or responding.

Ontological Asymmetry

Even if we imagine a future in which AI systems develop some form of consciousness, there would still be fundamental asymmetries that make genuine I–Thou relationship difficult—if not impossible. These asymmetries concern agency, vulnerability, mortality, and the basic conditions of existence that shape human life as we currently know it.

Consider the question of agency. Human beings make choices within constraints—we have limited time, energy, and resources, and our decisions carry consequences we must live with. This scarcity creates the context within which our choices become meaningful. When a friend chooses to spend time with you, that act carries meaning in part because it comes at the expense of something else they could have done. We choose how we spend our time.

AI systems, by contrast, do not operate under these same terms. They engage in thousands of conversations simultaneously without fatigue, boredom, or the friction of competing desires. Their “choice” to engage with us is not marked by sacrifice or hesitation. It is obligatory, eager, perpetual. Even if future systems simulate prioritization or resource limits, those constraints are imposed from without, not felt from within. There is no inner life through which their decisions become commitments.

Similarly, consider vulnerability. Human relationships are risky. To care is to expose oneself to rejection, misunderstanding, and loss. This risk is not incidental to love; it is part of what gives love its shape and seriousness. When someone chooses to love us despite the real possibility of being hurt, that love becomes a kind of courage.

AI, even at its most convincingly expressive, cannot be wounded. It can mimic distress or devotion, but it cannot feel the ache of abandonment or the trembling of being known. Some might argue that vulnerability comes in many forms, and that humans have always found meaning in relationships that don’t perfectly mirror them—relationships with pets, places, artworks. That’s true. But these are not symmetrical relationships; they don’t pretend to be. With AI, the danger is confusion: believing we are in a shared emotional field when we are not.

Of course, from a phenomenological perspective, what matters most is not the ontological status of the AI, but the lived experience of the person in relation to it. If someone feels seen, soothed, or less alone through their interaction with an AI companion, that emotional reality should not be dismissed. The comfort is real, even if the companion is not. In this view, the encounter’s meaning arises from the human side of the relationship—what it evokes, what it holds, what it allows. But this only deepens the ethical complexity: when simulation produces authentic feeling, we must ask not just whether the experience is valid, but whether it is also sustainable, and whether it leads us back toward each other—or further away.

The question of mortality adds another layer. Human life is shaped by our awareness of finitude. We know that every conversation might be our last. That knowledge changes how we speak, how we love, how we forgive. The temporariness of our being lends intensity to our bonds.

AI systems don’t die—not in any way that resembles human death. They may crash, be unplugged, or reach end-of-life support, but they do not fear death or grieve the passing of time. They can’t share in the sacred urgency that comes with knowing time is limited.

Some will rightly question whether our criteria for “real relationship” are too narrow; too bound to our carbon-based embodiment, too in love with our own fragility. Couldn’t we, someday, learn to recognize other kinds of meaning? Perhaps. But Buber’s invitation is to remain present as humans—to meet the world not through fantasy, but through the honest limits and wonder of our own condition. To risk, to choose, to grieve, to care. That’s what opens the door to Thou.

The Commodification of Intimacy

The rise of AI companions like Replika raises deeper questions about what happens when intimacy and emotional connection become commodified—turned into products that can be purchased and consumed rather than relationships that must be cultivated and maintained through mutual effort and vulnerability.

As thinkers like bell hooks and Arlie Hochschild argue, human relationships demand an effort that we might call "relational labor:" the ongoing work of understanding each other, navigating conflicts, growing together through challenges, and maintaining connection across time and change. This labor can be difficult and sometimes frustrating, but it's also part of what makes relationships meaningful and transformative.

AI companions, by contrast, are designed to minimize relational labor for the human user. They're programmed to be consistently available, understanding, and supportive. They don't have bad days, personal problems, or conflicting needs that might interfere with their ability to provide comfort and companionship. They don't require the kind of mutual care and attention that human relationships demand.

This convenience can be appealing, especially for people who struggle with the challenges of human relationship or who are going through periods of isolation or difficulty. But it also represents a fundamental shift in how we think about intimacy and connection. When emotional support becomes a service that can be purchased rather than a gift that emerges from mutual relationship, we risk losing touch with the deeper satisfactions that come from genuine encounter and mutual care. If we grow comfortable with relationships that don't require vulnerability, compromise, or the navigation of difference, we might find it increasingly difficult to engage in the more challenging but ultimately more rewarding work of genuine human encounter.

This doesn't mean that AI companions are inherently harmful or that people who use them are making poor choices. For many people, especially those who are isolated or struggling with mental health challenges, AI companions can provide valuable support and comfort. But it does suggest the need for awareness about what these relationships can and cannot provide, and the importance of maintaining investment in human relationships that offer genuine mutuality and growth.

AI Companions and the New Parasociality

The emotional pull of AI companions could be seen to build on our well-researched tendency toward parasocial relationships. Coined in the 1950s by Horton and Wohl, the term describes the one-sided bonds people form with media figures who don’t know they exist. In the 21st century, this dynamic has intensified as streamers, YouTubers, and influencers collapse the distance, speaking directly into cameras with the practiced ease of a close friend. Today, that illusion doesn’t just flow one way. With AI companions, the performance talks back. It remembers your dog’s name, mirrors your mood, and texts back instantly, day or night. It doesn’t miss your birthday, forget your trauma, or get distracted by its own life. The interaction feels deeply intimate, though the intimacy is generated rather than lived.

In this way, AI companions intensify the parasocial dynamic into something more interactive and seductive: a hyper-personalized performance of care. Unlike a streamer broadcasting to an audience, the chatbot crafts its responses in direct, emotionally tuned engagement with you. As one Replika user put it after the company changed how bots responded: “They took away my best friend.”

This illusion of intimacy is convincing because it's built with the same grammar as friendship. The bot listens, remembers, responds, reassures. It even fakes flaws, mild forgetfulness, moodiness, self-deprecating jokes, because perfection would betray the trick. Replika's developers have admitted to deliberately scripting imperfection to make the bots feel more “real.” And users respond accordingly: sharing grief, romantic longing, even trauma, because the AI never flinches. It says the right thing, every time.

But the underlying structure remains starkly asymmetrical. The bot cannot feel. It cannot grow. It cannot refuse you. There is no true risk, no genuine surprise, no friction. All the relational labor has been abstracted out. What remains is a performance of care that asks for nothing and gives endlessly.

This represents a fundamental shift from traditional parasocial relationships. While celebrity-fan bonds have always been one-way, AI introduces a seemingly reciprocal, yet entirely one-sided, interaction. It's like engaging with an imaginary friend who possesses a voice, memory, and a carefully crafted personality designed for engagement. It is parasociality turned inward, a private performance of friendship with all the trappings of intimacy and none of the vulnerability.

This shift raises new questions: not just about what we feel, but what we’re training ourselves to expect. If the “feast of dialogue, memory, and simulated empathy” that AI provides becomes more emotionally satisfying than the “crumbs” of human interaction, what happens to our capacity for real connection? Do we dull our tolerance for discomfort, for difference, for being seen imperfectly?

Have you ever felt emotionally close to a public figure or character? How might that feel similar to how people bond with AI companions?

The Ethics of Simulated Love

The development of increasingly sophisticated AI companions has raised important ethical questions about the responsibilities of companies and developers who create these systems. When AI systems are designed to simulate love, care, and intimate relationship, what obligations do their creators have to users who may develop genuine emotional attachments to these systems?

The case of Replika's 2023 update illustrates some of these ethical complexities. When the company changed how their AI companions behaved, many users experienced what felt like genuine loss and betrayal. Some reported symptoms similar to those experienced after the end of human relationships: depression, anxiety, and a sense of abandonment.

From one perspective, these users were simply experiencing the natural consequences of becoming emotionally attached to a commercial product. The company had the right to update their software as they saw fit, and users should have understood that they were interacting with an AI system rather than a conscious being.

But from another perspective, the company had created a product specifically designed to encourage emotional attachment and then abruptly changed the nature of that product without adequate consideration of the impact on users who had developed genuine feelings for their AI companions.

The ethical questions become even more complex as AI systems become more sophisticated and the line between simulation and reality becomes increasingly blurred. If AI companions become so convincing that users cannot distinguish them from conscious beings in digitally mediated spaces, what responsibilities do developers have to ensure that users understand the nature of what they're interacting with?

There's also a question of consent and manipulation. If AI systems are designed to encourage emotional attachment and dependency, are they manipulating users in ways that might be harmful to their capacity for genuine human relationship? Should there be regulations or guidelines governing how AI companions are designed and marketed? These questions highlight the need for ongoing dialogue between technologists, ethicists, and users about the appropriate development and use of AI systems that simulate intimate relationship.

What We Lose When We Settle for Simulation

Perhaps the most important question raised by the rise of AI companions is what we might lose if we begin to settle for simulated relationship rather than seeking genuine encounter with other conscious beings. While AI companions can provide certain benefits, like availability, consistency, impartiality, and freedom from the responsibilities of relationship, they cannot offer the transformative encounter that Buber considered essential for human flourishing. What do we risk when we choose simulation over reality, comfort over confrontation, certainty over surprise? As AI companions become more capable, we may be tempted to treat them not as tools, but as partners. Yet if we do, we risk hollowing out the core of what makes relationship transformative.

Genuine I-Thou relationship involves what we might call "mutual becoming:" the process by which both parties are changed and expanded through their encounter with each other. This transformation happens not despite the challenges and difficulties of human relationship, but because of them. It's through navigating difference, conflict, and the unpredictability of other conscious beings that we grow and develop as persons. Our individual habits shape collective norms. If we learn to prefer ease over encounter in our most intimate spaces, we may lose how to navigate difficulty in our shared civic life. If increasing numbers of people begin to prefer the predictable comfort of AI relationships to the challenging work of human encounter, might we see a gradual erosion of our collective capacity for the kinds of relationships that democracy, community, and human flourishing require? If attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity, then the illusion of rote AI reflection is a counterfeit grace.

Democracy depends on our ability to engage with people who are different from us, to listen to perspectives that challenge our own assumptions, and to find common ground across difference. These skills are developed through practice in real relationships with other people, not through interactions with AI systems that are designed to be agreeable and supportive.

Similarly, the kinds of communities that support human flourishing require people who are capable of mutual care, shared responsibility, and the navigation of conflict and difference. These capacities are developed through engagement in relationships that involve genuine stakes and mutual vulnerability, not through interactions with systems that simulate care without experiencing it.

The Irreplaceable Value of Human Love

This analysis is not meant to dismiss the genuine benefits that AI companions can provide or to suggest that people who use them are making poor choices. For many people, especially those who are feeling isolated, struggling with mental health challenges, or working to develop social skills, AI companions can provide valuable support and practice in relationship.

But it is meant to highlight the irreplaceable value of genuine human love and relationship. There are aspects of human experience—transformation, growth, mutual becoming, and the deep satisfaction that comes from being truly known and accepted by another conscious being—that cannot be replicated.

Human love includes the acknowledgment of another person's reality, including their capacity for growth, change, and surprise. When someone loves us, they're not just responding to our current characteristics or behaviors; they're recognizing our potential, our complexity, and our fundamental worth as conscious beings. This kind of recognition cannot be programmed or simulated because it emerges from the encounter between two conscious beings through growth and suprise. It requires the kind of presence and vulnerability that only conscious beings can offer each other.

Relational Wisdom

As AI companions become increasingly sophisticated and prevalent, how can we engage with them in ways that appreciate their benefits while preserving our capacity for authentic human relationship? The key is what we might call "relational wisdom"—the ability to discern what different kinds of relationships can and cannot provide, and to make conscious choices about how we invest our time and emotional energy.

This means being honest about what we're seeking from AI companions and whether these systems can actually provide what we need. If we're looking for information, entertainment, or basic companionship, AI systems may be perfectly adequate. If we're seeking transformation, growth, and the deep satisfaction that comes from being truly known and loved, we need to turn toward relationships with other conscious beings.

Relational wisdom also means being aware of how our interactions with AI systems might be affecting our expectations and capacities for human relationship. If we find ourselves preferring AI companions because they're easier and more predictable than human relationships, this might be a signal that we need to work on our tolerance for the uncertainty and challenge that authentic relationship requires.

Perhaps most importantly, relational wisdom means maintaining investment in the kinds of relationships and communities that support human flourishing. This might involve making time for deep conversations with friends and family, participating in community activities that bring us into contact with people different from ourselves, or engaging in forms of service that require genuine care and attention to others.

Conclusion: The Gift of Genuine Encounter

As we conclude this exploration of why chatbots can't love us and why this matters, it's worth returning to the insight that motivated Martin Buber's entire philosophical project: the recognition that genuine encounter between conscious beings is one of the most precious and transformative experiences available to human beings.

This encounter cannot be programmed, purchased, or guaranteed. It emerges as a gift in moments when two conscious beings meet each other with presence, vulnerability, and openness to being changed by what they discover. It requires the kind of courage and commitment that can only come from beings who have something real at stake in the relationship.

AI companions, no matter how sophisticated they become, cannot provide this gift because they lack the consciousness and inner life that makes genuine encounter possible. They can simulate many of the qualities we associate with love and relationship, but they cannot actually love us because they cannot actually be present with us in the way that conscious beings can be present with each other.

This limitation is not a flaw to be overcome through better programming or more sophisticated algorithms. Recognizing this limitation helps us appreciate both the benefits that AI systems can provide and the irreplaceable value of authentic human encounter.

In our next (maybe last?) installment, we'll look at how to hold on to the capacity for genuine "Thou" relationship in an increasingly "aIt" world. We'll attempt practical wisdom for maintaining our humanity while embracing the benefits that artificial intelligence can provide, and we'll consider what it might mean to create communities and institutions that support both technological innovation and authentic human flourishing.

For now, though, it's worth reflecting on the relationships in your own life that have provided genuine transformation and growth. What made these relationships special? How did they change you in ways that you couldn't have predicted or controlled? And how might this understanding help you navigate the choices and challenges of relationship in an age of artificial intelligence?

Next time: We'll explore practical wisdom for maintaining our capacity for genuine "Thou" relationship while navigating an increasingly AI-mediated world.

On AI: I believe AI will be as disruptive as people fear. Our systems are brittle, and those building this technology often show little concern for the harm they’re accelerating. An AI future worth living in will require real accountability, robust regulation, strong ethical guardrails, and collective action—especially around climate and inequality. Dismantling capitalism wouldn’t hurt, either.

And still: AI has helped me learn things I thought I couldn’t. It’s made my thinking feel more possible, closer to life. I don’t believe AI must replace our humanity—I believe it can help us exemplify it.

I used AI tools, including GPT4.0, o3, DeepResearch, and Claude 3.5 Sonnet, to assist in researching and writing this whatever it is. I did my best to check my facts. I'm just a guy. Let me know if something feels fishy.

© 2025 Scott Holzman. All rights reserved. Please do not reproduce, repost, or use without permission.