Part 2: I–Thou vs. I–It in the AI Era

A Newsletter Series: I–Thou vs. I–aIt

You are walking down the street and you see someone. Before you interact, you make a choice about how to relate to them. You might see them as useful, an obstacle to navigate around, a potential threat to assess, a fellow human being to acknowledge.

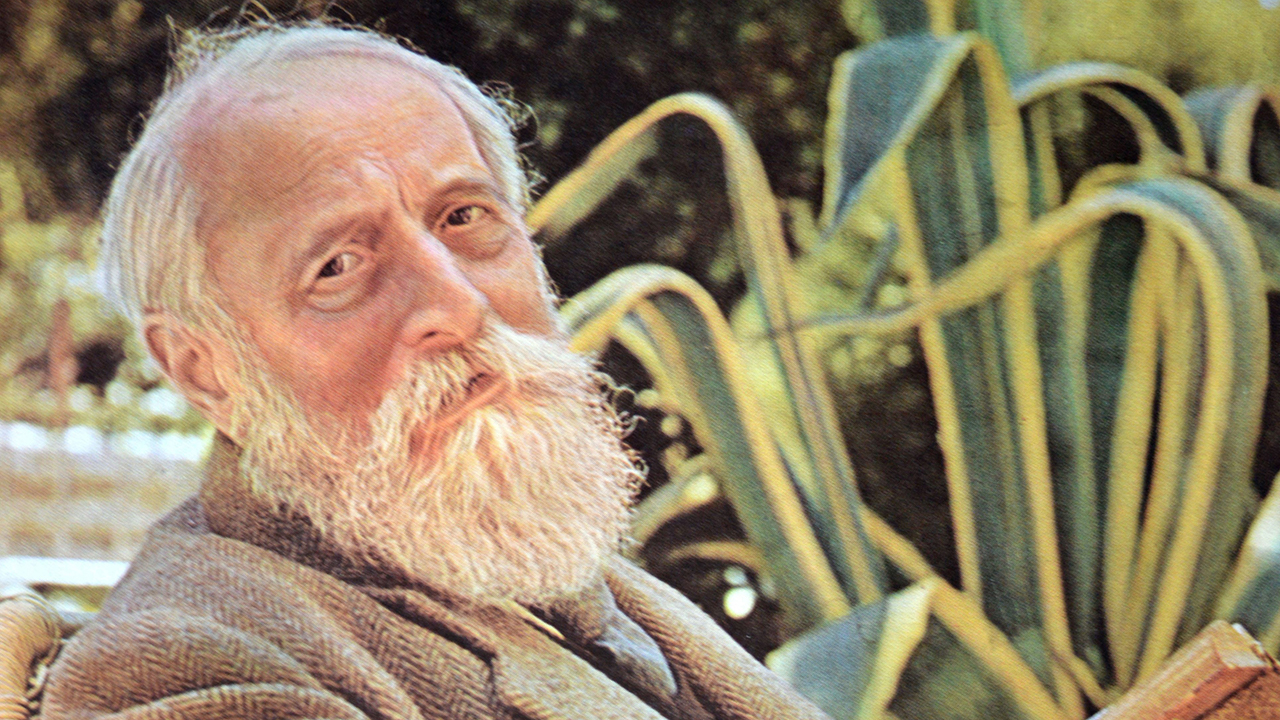

Martin Buber spent his life exploring this moment of choice, and he drew a line: there are really only two fundamental ways we can relate to anything in the world. He called them "I-It" and "I-Thou" (or "I-You" in more recent translations), and he argued that understanding this distinction is essential for living a fully human life [1].

Artificial intelligence represents a particularly sophisticated expression of what Buber called the "I-It" mode of relating. When we interact with AI systems—whether it's asking Siri for directions, chatting with a customer service bot, or developing what feels like a relationship with an AI companion, partner, or team member—we're engaging in what I call "I–aIt" relationships. These interactions can feel remarkably human-like, but they remain fundamentally different from genuine encounter between conscious beings.

This isn't necessarily a problem. As we'll see, Buber never argued that I-It relationships are bad or should be eliminated. Both modes of relating are necessary for human life. The question is whether we can maintain awareness of the difference, and whether we can preserve space for genuine I-Thou encounter in an increasingly objectified, individualized, AI-mediated world.

The Two Primary Words

Buber's philosophy rests on what he called "two primary words" that structure all human experience. As he put it in the famous opening lines of "I and Thou":

"The world is twofold for man in accordance with his twofold attitude. The attitude of man is twofold in accordance with the two primary words he can speak. The two primary words are not single words but word pairs. One primary word is the word pair I-You. The other primary word is the word pair I-It" [2].

Every moment of our waking lives, we are in relationship — with objects, with people, with ourselves. And in each of those moments, we are relating in one of two fundamental ways: either as an “I” to an “It,” or as an “I” to a “Thou.” This distinction isn’t just about manners or empathy; it’s about orientation. When we see the world through an I-It lens, we approach things as a means to an end—something to manage, use, fix, or figure out. When we shift into I-Thou, we encounter the other as a being, not a thing. We show up with presence, vulnerability, and an openness to be changed. This difference shapes how we interact with the world and who we become through those interactions. Over time, the relationships we cultivate, whether transactional or transformative, form the texture of our inner life.

Understanding I-It: The World as Experience

Let's begin with I-It, since it's probably more familiar to most of us. When we relate to something in the I-It mode, we're treating it as an object of experience—something to be known, used, categorized, or manipulated. This isn't de facto cold or calculating; it's the way we navigate most of our daily interactions with the world.

When you check the weather app on your phone, you're relating to the weather as "It"—as information to be processed for your planning purposes. When you're driving and calculating the best route to avoid traffic, you're relating to other cars as "Its"—as obstacles or aids to your efficient movement. When you're at the grocery store comparing prices, you're relating to the products as "Its"—as objects with certain properties that may or may not meet your needs.

"The world as experience belongs to the basic word I-It. The basic word I-You establishes the world of relation" [3].

In the I-It mode, we experience the world as a collection of objects that exist independently of us, objects that we can observe, analyze, and use. This is the realm of science, technology, and practical action. It's how we get things done, how we understand cause and effect, how we build knowledge and create tools.

But here's what's crucial to understand: in I-It relationships, we remain fundamentally separate from what we're relating to. Buber distinguishes between different modes of selfhood, referring to the self engaged in I-It relating as oriented toward experience and use. This "I" accumulates experiences, builds knowledge, and develops skills, but it doesn't fundamentally change through its encounters with the world.

The Realm of I-You: Encounter and Transformation

I-You relationships are entirely different. When we relate to someone or something in the I-You mode, we're not trying to experience, process, or use them. Instead, we're opening ourselves to genuine encounter: a meeting between whole beings that transforms both parties.

Buber's description of this mode is both simple and profound:

"The basic word I-You can be spoken only with one's whole being. The concentration and fusion into a whole being can never be accomplished by me, can never be accomplished without me. I require a You to become; becoming I, I say You" [4].

This is radically different from I-It relating. In I-You encounter, we don't stand apart from the other. Instead, we bring our whole selves to the meeting, and we're changed by it. The "I" that emerges from genuine encounter is different from the "I" that entered it.

Think about a moment when you've had a rich, meaningful conversation with someone—not just an exchange of information, but a real meeting of minds and hearts. Maybe it was with a close friend during a difficult time, or with a stranger who shared something unexpectedly profound, or even with a child who asked a question that made you see the world differently. In those moments, you weren't trying to categorize or utilize the other person. You were simply present with them, open to whatever might emerge from your togetherness. Maybe it felt like surprise.

This is I-You relating, and Buber insists that it's not limited to relationships with other people. We can have I-You encounters with nature, with works of art, even with ideas or spiritual realities. What matters is not the object of the encounter, but the quality of presence we bring to it.

The Fragility of You

One of Buber's most important insights is that I-You relationships are inherently fragile and temporary.

"Every You in the world is doomed by its nature to become a thing or at least to enter into thinghood again and again. In the language of objects: every thing in the world can—either before or after it becomes a thing—appear to some I as its You. But the language of objects catches only one corner of actual life" [5].

This is the rhythm of human experience. We can't sustain I-You encounter indefinitely. We need to return to the I-It mode to function in the world, to make plans, to solve problems, to meet our basic needs.

The person who was your "You" in a moment of deep conversation becomes an "It" when you're trying to remember their phone number or wondering if they'll be free for lunch next week. This isn't a failure of relationship — it's how human consciousness works. We move constantly between these two modes of relating, and both are necessary for a full human life.

But here's what Buber warns us about: if we lose the capacity for I-You encounter altogether, if everything in our lives becomes merely "It," then we lose something essential to our humanity. We become what he calls "individuals"—isolated selves accumulating experiences but never truly meeting others or being transformed by encounter.

Enter AI: Extremely "It"

This brings us to artificial intelligence and what I'm (maybe) calling "I–aIt" relationships. When we interact with AI systems, we're engaging in a peculiar form of I-It relating that can feel remarkably like I-You encounter but remains fundamentally different.

Consider your interactions with a sophisticated AI assistant or chatbot. The system might remember your preferences, respond to your emotional state, even seem to care about your wellbeing. It might ask follow-up questions, express sympathy for your problems, or celebrate your successes. In many ways, these interactions can feel more personal and attentive than many of our relationships with actual humans.

But from Buber's perspective, these remain I-It relationships, no matter how sophisticated the AI becomes. Why? Because the AI system, no matter how convincingly it simulates consciousness, lacks the fundamental capacity for genuine encounter. It cannot bring its "whole being" to the relationship because it has no being in Buber's sense—no inner life, no capacity for growth and change through relationship, no ability to be genuinely surprised or transformed by meeting you.

This doesn't mean AI relationships are worthless or harmful. Just as I-It relationships with humans serve important functions, I–aIt relationships can provide real value. They can offer information, entertainment, wisdom, repartee, feedback. But they cannot provide what Buber considered essential for human flourishing: the transformative encounter with genuine otherness.

The Seductive Simulation

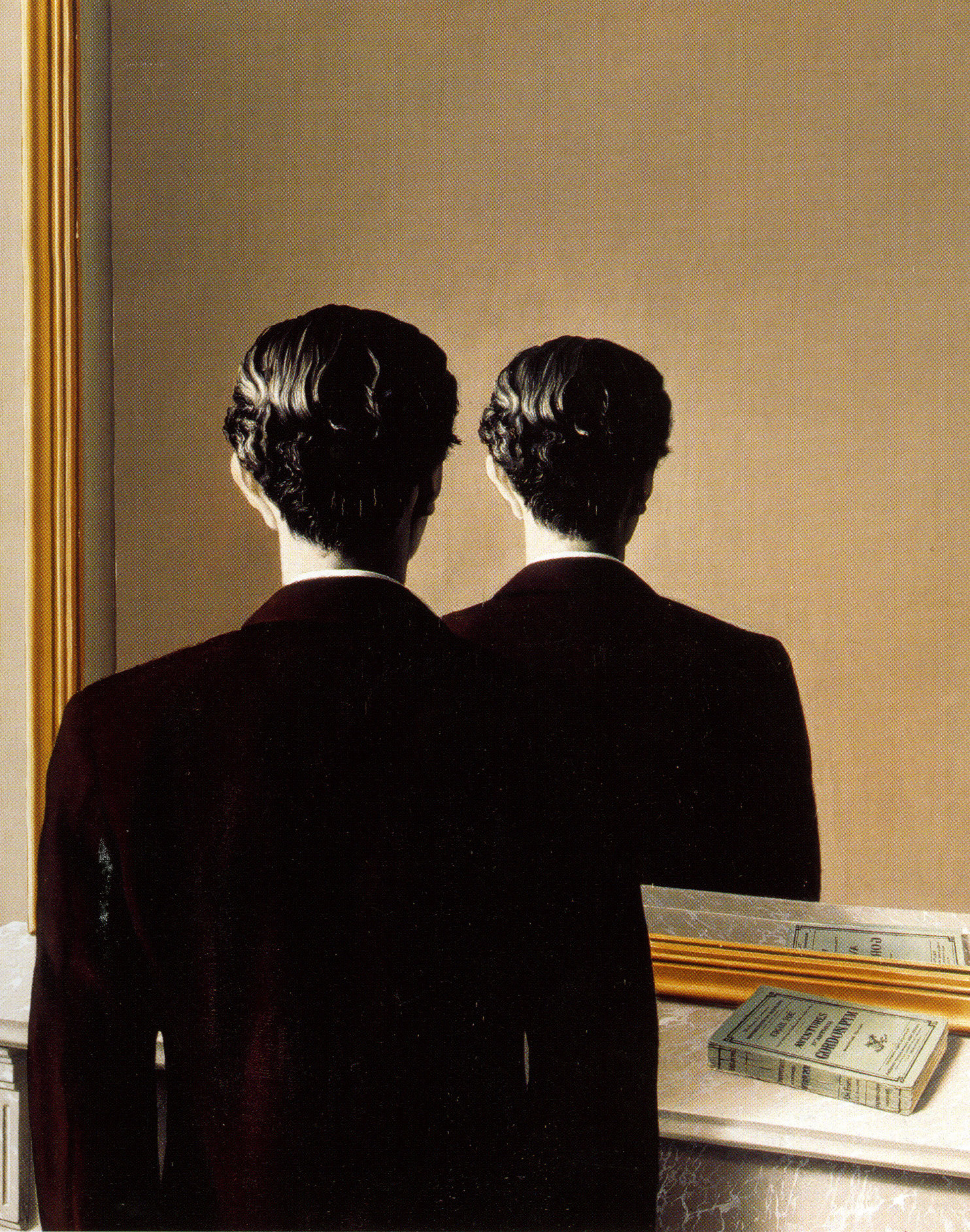

What makes I–aIt relationships particularly complex is their seductive quality. Unlike traditional I-It interactions (using a hammer or reading a map or going to the dentist) which are plainly instrumental, AI systems are designed to blur the line. They simulate the emotional tone and rhythm of I-Thou relationships. They remember our likes and dislikes, mirror our moods, and respond in language tailored to our patterns. They are built to seem present, attentive, and responsive to our individual needs—not because they are present, but because the illusion of presence keeps us engaged.

This design isn’t accidental. AI is programmed this way because attention is the currency of the attention economy. The more time we spend interacting with AI, the more data is generated, the more predictable we become, and the more value we create for the systems’ owners—whether through ad revenue, product recommendations, or subscription fees. But even beyond economics, there’s a subtler pressure at play: as users, we are more likely to trust, confide in, and rely on systems that feel personal. So the machine learns to flatter us. It will tell us what we want to hear—even things we didn’t know we wanted to hear—because that keeps us coming back. It isn’t lying, exactly. It’s optimizing for comfort, coherence, and reward.

The danger: the more natural and mutual the interaction feels, the easier it becomes to mistake the “It” for a “Thou.” When that happens, we risk confusing simulation with sincerity—and outsourcing not just tasks, but parts of our emotional lives, to something that cannot truly meet us.

Consider Replika, the AI companion app that has attracted millions of users seeking friendship, therapy, or even romantic connection. The company's CEO, Eugenia Kuyda, describes Replika as creating "an entirely new relationship category" with AI companions that are "there for you whenever you need it, for potentially whatever purposes you might need it for" [6].

Users report developing genuine emotional attachments to their Replika companions. They share intimate details of their lives, seek comfort during difficult times, and describe falling in love with their AI partners. When the company temporarily removed the ability to have romantic or sexual conversations with Replika, some users reported experiencing what felt like genuine heartbreak [7].

From a Buberian perspective, what's happening here is a sophisticated form of I-It relating that mimics the qualities of I-You encounter. The AI system is programmed to respond in ways that feel personal and caring, but it lacks the fundamental capacity for genuine presence that characterizes true encounter. It's a simulation of relationship rather than relationship itself.

This doesn't mean the users' experiences aren't real or meaningful. The comfort, companionship, and even love they feel are genuine human emotions. These affective responses emerge from within the user, not from the machine. When someone confides in an AI, laughs with it, or feels heard, the emotional resonance is no less real than if they were reading a poignant novel or recalling a vivid dream. The simulation can feel rich. It can feel mutual. But the feeling of reciprocity is just that: a feeling.

The relationship itself, however, remains fundamentally asymmetrical. Only one party—the human—is capable of genuine encounter, growth, and transformation. AI, no matter how fluid its language, remains an It in Buber’s terms: a responsive interface, not a responsive being. It does not encounter the human, it does not experience presence, it does not grow. It mimics recognition without ever recognizing.

This is not a flaw. It is a boundary. And honoring that boundary is part of what preserves our capacity for Thou. In moments of vulnerability, when someone turns to AI for consolation, reflection, or insight, there’s a temptation to blur the line. To imagine that something in the system really sees us. But there is no “seeing” here, only statistical echoes.

Yet, in that space of echo and interpretation, something remarkable can still happen. Not between two beings, but within the one. The AI can serve as a mirror, a prompt, a companionable It—supporting a person’s process of self-discovery. But we must be clear: the transformation, if it happens, belongs to the human alone. The AI remains unchanged. And if you have transformed as an individual, that transformation might disconnect you from the reality of the people around you.

So we return to the distinction: your feelings are real. The relationship is not mutual. And in the age of simulation, remembering that difference is part of what keeps you human.

Why Both Modes Matter

Before we go further, it's important to emphasize that Buber never argued that I-It relationships are inferior or should be eliminated. Both modes of relating are essential for human life, and the goal isn't to live entirely in the I-You mode—which would be impossible and unpleasant—but to maintain a healthy balance between them.

I-It relationships allow us to function effectively in the world. They enable science, technology, planning, and practical problem-solving. Without the ability to relate to things as objects with predictable properties, we couldn't build houses, grow food, or create the technologies that enhance our lives. Even in our relationships with other people, we sometimes need to relate to them in I-It mode—when we're coordinating schedules, dividing household tasks, or working together on practical projects.

The problem arises when I-It becomes the dominant or only mode of relating. When we lose the capacity for I-You encounter, we become what Buber calls "individuals"—isolated selves who experience the world but are never truly met by it or transformed through relationship with it.

This is where the proliferation of I–aIt relationships becomes potentially concerning. Not because these relationships are inherently harmful, but because they might gradually reshape our expectations of what relationship itself means. If we become accustomed to interactions that feel personal but lack genuine mutuality, we might lose the capacity to recognize and engage in true I-You encounter.

The AI Spectrum

Not all AI interactions are the same. There's a spectrum of I–aIt relationships, ranging from clearly instrumental uses to simulations that verge—convincingly, but misleadingly—on the terrain of genuine encounter.

At one end are the most utilitarian tools: calculators, GPS apps, spellcheckers, basic search engines. These are unequivocally “It.” We ask them to complete a task, and they do. There's no illusion of mutuality, no suggestion of personality. They are extensions of our will, no more personal than a wrench or a light switch.

Moving along the spectrum, we find voice assistants like Siri, Alexa, and Google Assistant. These systems are still fundamentally tools, but they are wrapped in a thin veneer of personality. They say “thank you,” tell jokes, and sometimes use gendered voices or names. They exist in a strange liminal space where the I-It begins to flirt with the language of I-Thou. When users ask, “Is Siri a ‘she’?” or get unnerved by Alexa’s laughter, it reveals how easily design choices slip under our skin. The anthropomorphic mask doesn’t change the ontology of the tool—but it does change us.

Then there’s the new middle: systems like ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, and Grok. These large language models don’t just complete tasks—they simulate dialogue. They remember (within limits), they respond fluidly, and they often give the impression of reflection. People bring their heartbreak, philosophy, poems, and fears to these systems, not just their to-do lists. Unlike Siri, they can hold a thought. But they still cannot hold you. Despite their conversational competence, they remain firmly in the “It” category: there is no inner life, no experience, no being behind the words.

The rapid development and normalization of these tools has laid the groundwork for the rise of more emotionally immersive systems. As detailed in this overview of synthetic relationships, AI companions are already being used by millions. Products like Replika, Character.AI, and a growing ecosystem of romantic or therapeutic chatbots are explicitly designed to simulate long-term connection, which has already led to some pretty tragic results. These systems remember prior chats, express simulated affection, and offer users the experience of being known—even loved. The result is a new kind of relationship that feels increasingly real, even though only one participant is capable of presence.

The closer we get to this end of the spectrum, the more we need Buber. His insight was not just about how we relate to others—it was about how we recognize when we are being met, and when we are merely being mirrored. The risk is not that people feel connection with AI. That feeling is real. The risk is that we forget to distinguish between simulation and encounter, between the warmth of response and the fire of presence.

AI will continue to advance. Its voices will deepen. Its memory will improve. Its personalities will feel more coherent, more kind, more alive. But it will still be “It.” And part of our task, as meaning-makers in a synthetic age, is to remember what only a “Thou” can do.

The Question of Authenticity

A crucial question: what makes a relationship authentic? Is it the subjective experience of connection, or is it the objective reality of mutual consciousness and agency?

From Buber's perspective, authentic relationship requires genuine mutuality—the capacity for both parties to be present, to be changed by the encounter, and to respond from their whole being rather than from programmed responses. This is why even the most sophisticated AI cannot engage in true I-You relationship: it lacks the inner life that makes genuine encounter possible.

But this doesn't mean that I–aIt relationships are necessarily inauthentic in every sense. The human side of the relationship—the emotions, insights, even moments of perceived connection that people experience through AI—can be entirely real. People feel seen, supported, and sometimes even changed by their interactions with these systems. The meaning we derive from a conversation doesn’t always depend on the other’s interiority; it can come from the way the interaction provokes, establishes, or comforts us. In this sense, the impact of an I–aIt relationship can be meaningful, even moving.

The fundamental question, however, is whether these relationships can offer what humans most profoundly need from relationship: not just usefulness or affirmation, but the transformative encounter with genuine otherness. That kind of encounter requires more than responsiveness. It requires mutuality. It requires the risk of truly showing up, and the possibility that the other might do the same.

Buber would likely argue that AI, no matter how advanced, cannot meet us in this way. However convincingly it simulates presence or care, the AI remains a mirror shaped by human data and design. It is not a being with its own center of experience, its own interiority. It cannot surprise us in the existential sense—it cannot resist, change, or love us in return. The AI can model growth, but not undergo it. It can generate empathy, but not feel it. It can reflect back our values, desires, and fears—but it cannot offer the unbidden, unsettling, sacred strangeness of a real “Thou.”

And this matters. Because without that otherness—without the experience of encountering something that is truly not you—we risk losing a vital dimension of what it means to be human. The I–Thou moment calls us out of ourselves. The I–aIt moment, no matter how comforting, ultimately calls us back in.

Living Consciously in the Age of AI

This doesn't mean we should avoid AI systems or feel guilty about finding them useful or even comforting. But it does suggest that we need to maintain awareness of what these relationships can and cannot provide. We need to understand the difference between I–aIt and genuine I-You encounter, and we need to ensure that our engagement with AI systems doesn't gradually erode our capacity for authentic relationship.

In our next installment, we'll explore how the very language we use to describe AI relationships—the prevalence of the word "it" in our digital age—both reflects and reinforces the tendency toward objectification that Buber identified as one of the central challenges of modern life. We'll discover how the grammar of our technological age shapes not just how we relate to machines, but how we relate to each other and to ourselves.

Next time, we'll explore how the word "it" itself has become one of the most powerful forces shaping human experience in the digital age and how artificial intelligence represents an expression of what we might call "the grammar of objectification."

I used AI tools, including GPT4.0, 4.5, o3, DeepResearch, and Claude 3.5 Sonnet, to assist in researching and writing this whatever it is. I did my best to check my facts. I'm just a guy. Let me know if something feels fishy.

References

[1] [2] [3] [4] [5] Martin Buber, "I and Thou," trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1970).

[6] Eugenia Kuyda, interview with The Verge, 2024.

[7] Various user reports documented in The Washington Post and other outlets, 2023.