Part 1: Martin Buber and the Trouble with "It"

A 5?-part Newsletter Series: on the I–Thou vs. I–aIt relationship

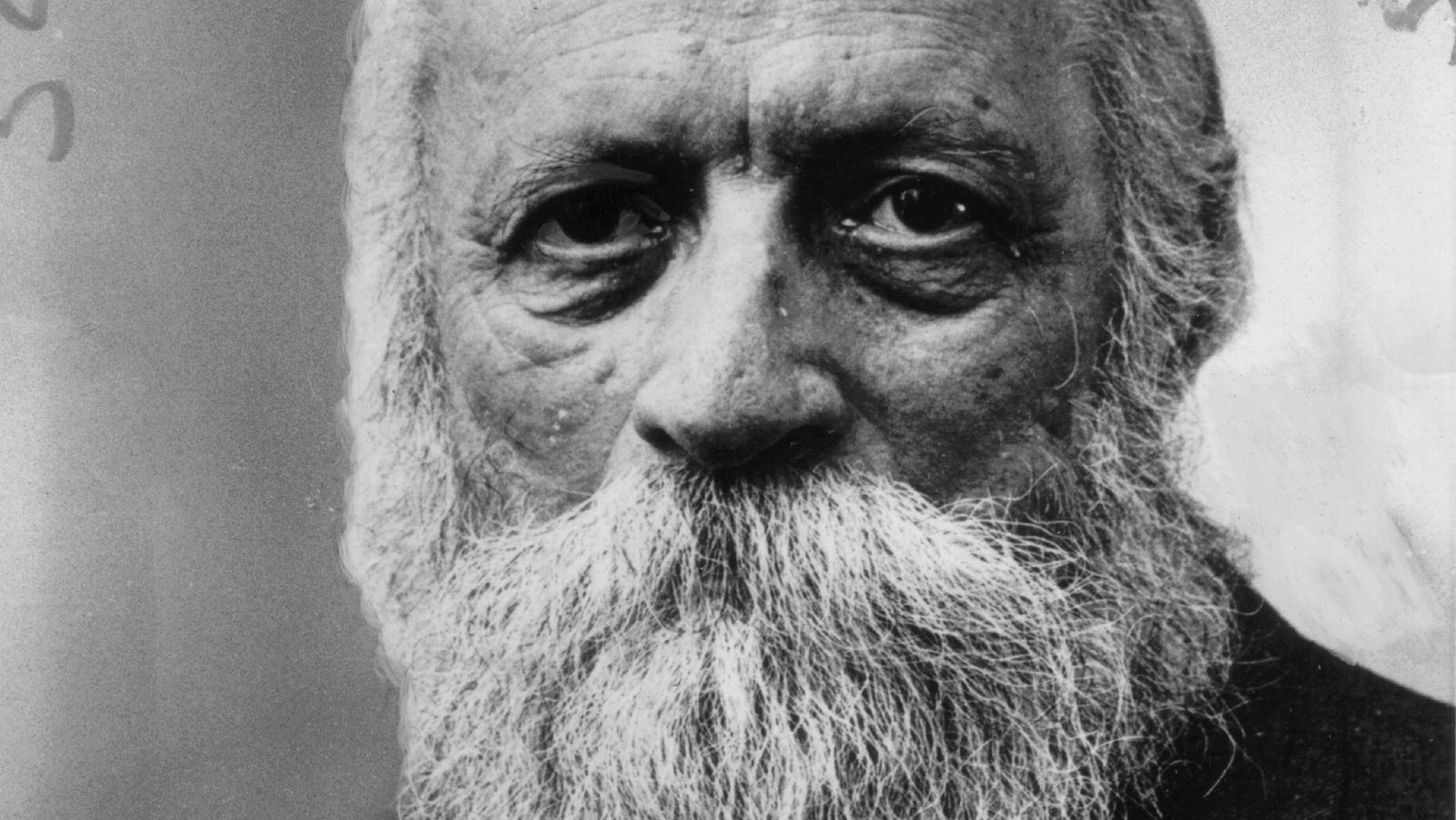

In 1882 Vienna, a four-year-old boy, Martin Buber, witnessed his family's disintegration. His mother departed, leaving his father overwhelmed, and young Martin was sent to live with his grandparents in Lemberg, presently known as Lviv in Ukraine. This child, described later as a "bookish aesthete with few friends his age, whose major diversion was the play of the imagination," would grow up to become one of the twentieth century's most influential philosophers of human relationship [1].

As he grew older, the world around Buber would unravel too. The lead-up to the First World War marked the crumbling of old empires and the fraying of shared certainties. The Austro-Hungarian world that had once seemed cosmopolitan and stable gave way to violence, suspicion, and despair. By the time Buber was publishing his most well-known book I and Thou in 1923, Europe was struggling to comprehend the moral devastation of a war that had claimed over 16 million lives. The French poet Paul Valéry captured the disillusionment of the moment in his essay titled The Crisis of the Mind: “We later civilizations… we too now know that we are mortal.” It was in this disturbed Earth of civilizational fracture that the seeds of his youthful heartbreak were sown and grown. Buber articulated his vision of relation: a plea for presence, mutuality, and the sacredness of encounter, while the world slid toward mechanization and innovative new destructions.

This is the first in a five-part series exploring Martin Buber's philosophy of "I and Thou" through the lens of our relationship with AI systems. We'll think about how Buber's century-old warnings about objectification have found perhaps their ultimate expression in what I'm (maybe) calling "I–aIt"—the peculiar way artificial intelligence embodies and amplifies the tendencies toward objectification that Buber spent his life trying to understand.

Context for a Philosopher

To understand why Buber's ideas matter for our AI moment, we need to spend some time in the world that shaped him. Martin Buber was born in 1878 into the twilight of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in a Vienna that was simultaneously the height of European sophistication and a powder keg of ethnic tensions that would soon explode into World War I [2].

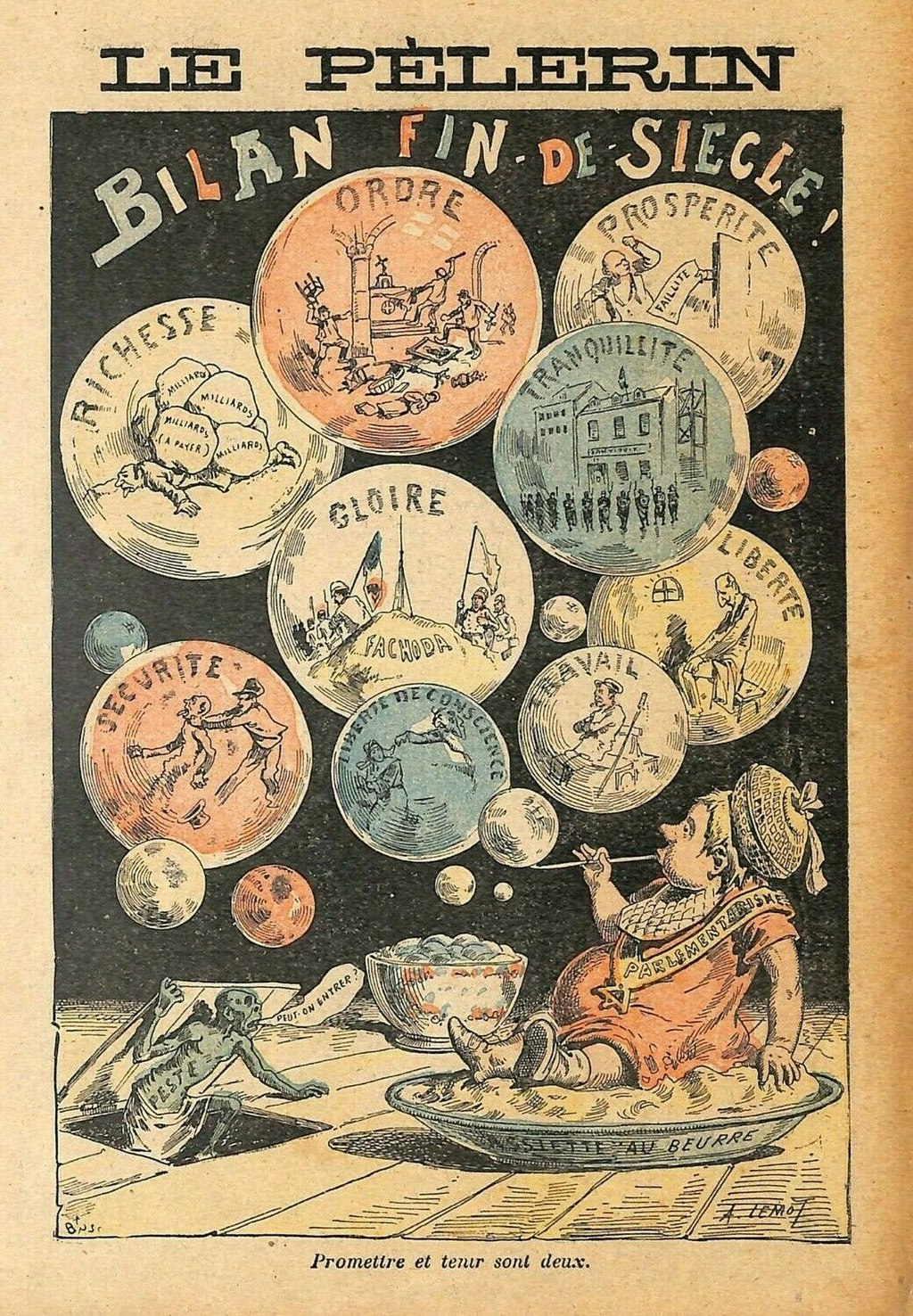

This was fin-de-siècle Vienna, described as a "cultural cauldron" of light opera and heavy neo-romantic music, French-style boulevard comedy and social realism, sexual repression and deviance, political intrigue and vibrant journalism. An atmosphere well captured in Robert Musil's unfinished 1930 novel The Man Without Qualities [3]. It was a world where everything solid was melting, where traditional certainties were giving way to modern anxieties. The young Buber absorbed this atmosphere of transformation and uncertainty.

“I dont believe in the Devil, but if I did I should think of him as the trainer who drives Heaven to break its own records.”

― Robert Musil, The Man Without Qualities

Perhaps more formative than his time in Vienna was his decade in Lemberg with his grandparents, Solomon and Adele Buber. Solomon was what Buber later called "a master of the old Haskala" who worked to bridge traditional Jewish learning with modern European culture [4]. He was wealthy enough to be called part of the "landed Jewish aristocracy," yet respected enough in traditional Jewish circles that his reputation would later open doors for Martin when he began exploring Hasidic mysticism.

This was Buber's first lesson in living between worlds. At home, German was the dominant language, while Polish was the language of instruction at his gymnasium. But he also absorbed Hebrew, Yiddish, and later Greek, Latin, French, Italian, and English. As the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy notes, "This multilingualism nourished Buber's life-long interest in language" [5]. More than that, it taught him that identity itself could be multilingual, multicultural, and fluid.

Paradoxically, the boy destined to become a philosopher of relationship lived a life of considerable isolation. He was home-schooled by his grandmother, had few friends his own age, and lived primarily in the world of his books and mind. This isolation may have been precisely what allowed him to see relationship so clearly when he began to study it. We sometimes need to experience the absence of something to understand its presence.

Modern and Mystic

When Buber was twenty-six, something shifted. He began studying Hasidic texts and was, in his own words, "greatly moved by their spiritual message" [6]. This wasn't just academic interest—it was a profound encounter with a way of being in the world that emphasized joy, presence, and the possibility of finding the sacred in everyday life.

Hasidism, the mystical Jewish movement which emerged in eighteenth-century Eastern Europe, taught that God could be encountered not just in formal prayer or study, but in every moment of daily life. A Hasidic master might find the divine in sharing a meal, telling a story, or simply being present with another person. As one scholar put it, Hasidism was "ethical mysticism" whose "dominant characteristic is joy in the good—in the good in every sense of the word, in life, in the world, in existence" [7].

For Buber, this was revelatory. Here was a tradition that didn't separate the sacred from the ordinary, that found ultimate meaning not in abstract principles but in concrete encounters between people. He would later describe Hasidism as "Cabbala transformed into Ethos"—mystical wisdom transformed into a way of living [8].

But Buber was also a thoroughly modern man, shaped by the philosophical currents of his time. He studied with some of the leading thinkers of the early twentieth century, absorbed the insights of existentialism, and was deeply influenced by the emerging field of psychology. His niche lay in his ability to bring these modern insights into conversation with ancient wisdom. Traditional Jewish scholars often viewed Buber with suspicion, seeing his interpretations of Hasidism as too romantic, too removed from the actual lived experience of traditional Jewish communities. As one contemporary observer noted, Buber's conception of Judaism was often met skeptically by his Jewish contemporaries but found receptive audiences among Protestant theologians and Christian thinkers [9].

Genuine Meeting Between Whole Persons

By the time Buber began writing "I and Thou" in 1916, he had identified what he saw as the central crisis of modern life: the tendency to treat other people, and indeed the world itself, as objects to be used rather than subjects to be encountered [10]. This wasn't just a philosophical problem—it was an existential and spiritual crisis that was reshaping human experience.

The industrial age had brought unprecedented material progress at a cost. People were increasingly becoming cogs in machines, both literally and metaphorically. The same scientific thinking that had unlocked the secrets of nature was being applied to human beings, reducing them to collections of measurable traits and predictable behaviors. What Buber called the "I-It" way of relating was becoming dominant. He saw that the problem wasn't just with how we organized society, but with how we thought about thinking itself. The Cartesian tradition that dominated Western philosophy since the seventeenth century was built on a fundamental separation between subject and object, between the thinking self and the world it thinks about. This separation, Buber argued, made genuine encounter nearly impossible.

As the Stanford Encyclopedia puts it, Buber's philosophy was concerned with "encounters between subjects that exceed the range of the Cartesian subject-object relation" [11]. He was looking for a way of being with others that didn't reduce them to objects of knowledge or manipulation, but allowed for genuine meeting between whole persons.

This is where Buber's personal history becomes philosophically significant. The child who had experienced the breakdown of his parents' relationship, who had lived between cultures and languages, and who had found in Hasidism a tradition that emphasized presence over doctrine—this person was uniquely positioned to see what was being lost in the modern world's rush toward efficiency and control, a rush that would ultimately culminate in the unprecedented devastation of World War I.

"I and Thou"

Buber began drafting what would become "I and Thou" during a time when the crisis of modern civilization was becoming impossible to ignore. The same technological and organizational capabilities that had brought progress were now being used to kill millions of people with unprecedented machine gun efficiency. The war made visible what Buber had already sensed: that treating people as objects, even toward “noble” goals, leads inevitably to dehumanization. "I and Thou" offered more than just a critique; it sought to define an alternative. Buber wanted to show that there was another way of being in the world, another way of relating to others that preserved their full humanity while still allowing for practical action. He called this the "I-You" relationship, and he argued that it was not only possible but essential for human flourishing.

“Spirit is not in the I but between I and You.”

The book that emerged was unlike anything in the philosophical tradition. As one scholar notes, Buber's "literary voice may be best understood as probingly personal while seeking communication with others, forging a path between East and West, Judaism and Humanism, national particularity and universal spirit" [12].This philosophy wasn't just for other philosophers; it was for anyone grappling with how to preserve genuine relationships in a world growing more impersonal.

When "I and Thou" was published in 1923, it became an instant classic. It was translated into English in 1937 and gained even wider influence when Buber began traveling and lecturing in the United States in the 1950s and 60s [13]. The book resonated deeply with many, articulating a widespread but unexpressed sentiment: that modern existence was creating barriers to genuine human connection.

“As long as love is “blind” - that is, as long as it does not see a whole being - it does not yet truly stand under the basic word of relation. Hatred remains blind by its very nature; one can hate only part of a being.”

Why Buber Matters Now

Today, nearly a century after "I and Thou" was first published, Buber's insights feel as relevant as ever. We live in an age where artificial intelligence can simulate conversation, where social media platforms algorithmically curate our relationships, where dating apps reduce potential partners to profiles. The tendency toward objectification that Buber identified has found loud expression in systems that literally treat human beings as data points to be processed. Buber's enduring value lies in his refusal to force a choice between relationship and technology, or between the personal and the practical. He asserts that both "I-It" and "I-You" ways of relating are essential to human existence. The challenge, therefore, isn't to eradicate objectification, but to appropriately manage its role.

As AI systems become more sophisticated in simulating human-like interaction, understanding our relationship with these technologies is crucial. These technologies are here to stay and will continue to evolve. The question is whether we can engage with them consciously, understanding what they can and cannot provide, rather than unconsciously allowing them to reshape our cultural expectations of what relationship itself means.

The next installment will delve into Buber's distinction between "I-It" and "I-You" and its relevance to our relationship with artificial intelligence. We will examine why he believed both relational modes are essential, and how their equilibrium dictates our flourishing as humans or our gradual disconnect from our deepest selves.

For now, though, it's worth sitting with the image of that four-year-old boy in Vienna, learning early that relationships can break but also that they can be rebuilt in new forms.

On AI: I believe AI will be as disruptive as people fear. Our systems are brittle, and those building this technology often show little concern for the harm they’re accelerating. An AI future worth living in will require real accountability, robust regulation, strong ethical guardrails, and collective action—especially around climate and inequality. Dismantling capitalism wouldn’t hurt, either.

And still: AI has helped me learn things I thought I couldn’t. It’s made my thinking feel more possible, closer to life. I don’t believe AI must replace our humanity—I believe it can help us exemplify it.

© 2025 Scott Holzman. All rights reserved. Please do not reproduce, repost, or use without permission.

I used AI tools, including GPT4.0, 4.1, 4.5, DeepResearch, and Claude 3.5 Sonnet, to assist in researching and writing this whatever it is. I did my best to check my facts. I'm just a guy. Let me know if something feels fishy.

References

[1] [2] [3] [4] [5] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. "Martin Buber." https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/buber/

[6] Jewish Virtual Library. "Martin Buber." https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/martin-buber

[7] Kenneth Rexroth. "The Hasidism of Martin Buber." https://www.bopsecrets.org/rexroth/buber.htm

[8] Gershom Scholem. "Martin Buber's Hasidism." Commentary Magazine. https://www.commentary.org/articles/gershom-scholem/martin-bubers-hasidism/

[9] Adam Kirsch. "Modernity, Faith, and Martin Buber." The New Yorker, April 29, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/05/06/modernity-faith-and-martin-buber

[10] [11] [12] [13] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. "Martin Buber." https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/buber/