I-Thou vs I-aIt

I–Thou vs. I–aIt is a five-part essay series that applies Martin Buber’s philosophy of relationship to the age of artificial intelligence. At the heart of Buber’s thought is the distinction between two modes of relation: I–It (objectifying, instrumental) and I–Thou (mutual, present, whole). The series proposes a third mode—“I–aIt”—to describe the unique dynamic that arises in human–AI interaction: one that feels personal but lacks true mutuality.

Drawing on Buber’s history, the work explores how his early 20th-century concerns about objectification and mechanization eerily anticipate our digital present. In particular, it shows how AI systems—especially chatbots and synthetic companions—simulate qualities of I–Thou encounter while remaining fundamentally I–It. These systems mirror us, flatter us, and generate emotional resonance, but they do not meet us with presence or undergo transformation themselves.

The series examines how language (especially the pronoun “it”) contributes to this confusion. Through comparisons across languages and translations, it reveals how our grammar encodes relational distance, shaping how we perceive and relate to others—including machines. It also connects these linguistic patterns to larger cultural phenomena: bureaucracy, surveillance capitalism, techno-optimism, and the gamification of emotion.

Ultimately, the project warns that if we grow too accustomed to simulated connection, we may lose our capacity to recognize or sustain real relationship. Yet it doesn’t reject AI—it calls for “relational discernment,” encouraging a conscious engagement with these tools while defending the sacredness of I–Thou moments. It’s a philosophical, poetic, and deeply human attempt to chart a moral vocabulary for life with machines.

Part 1: Martin Buber and the Trouble with "It"

A 5?-part Newsletter Series: on the I–Thou vs. I–aIt relationship

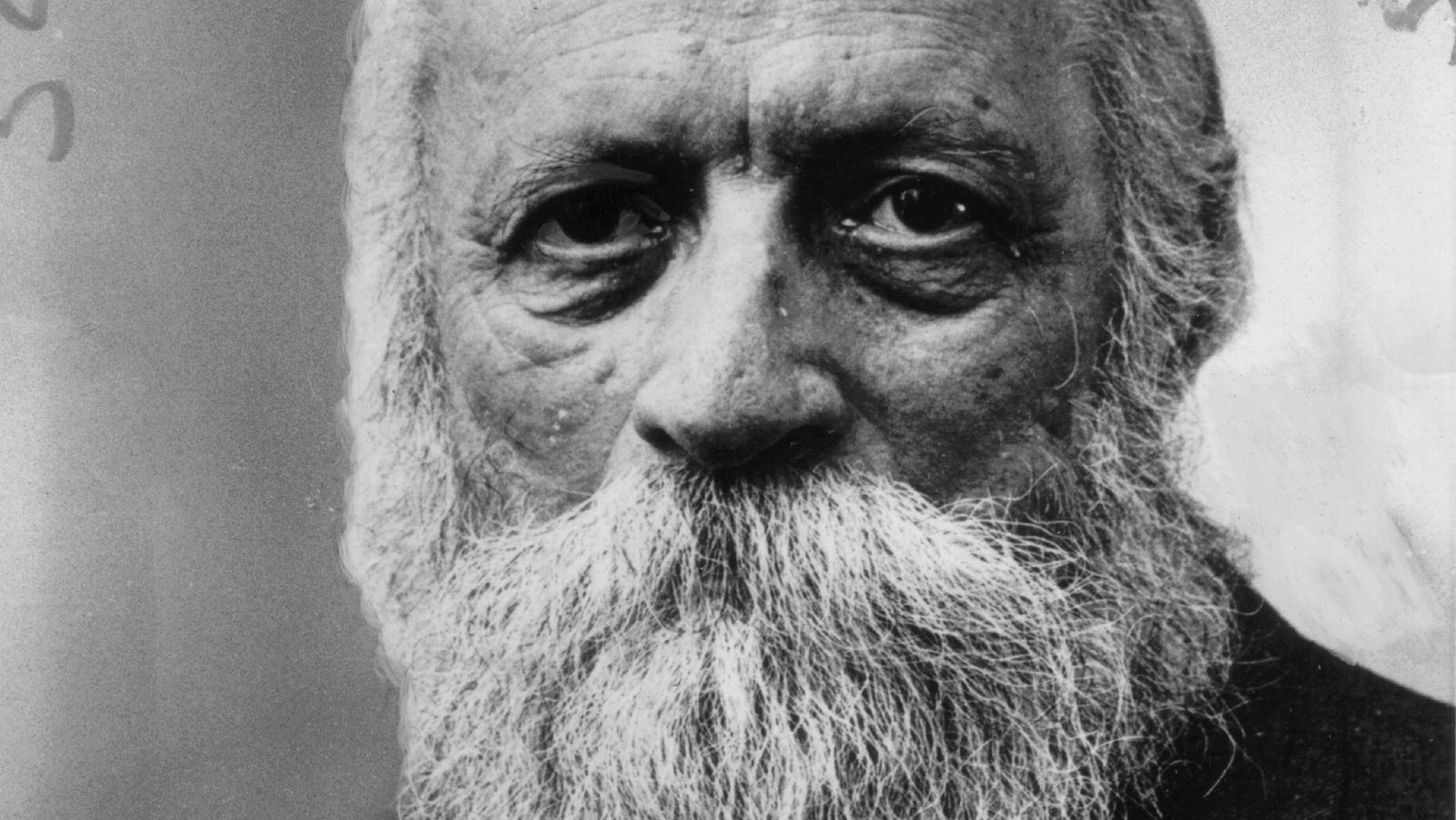

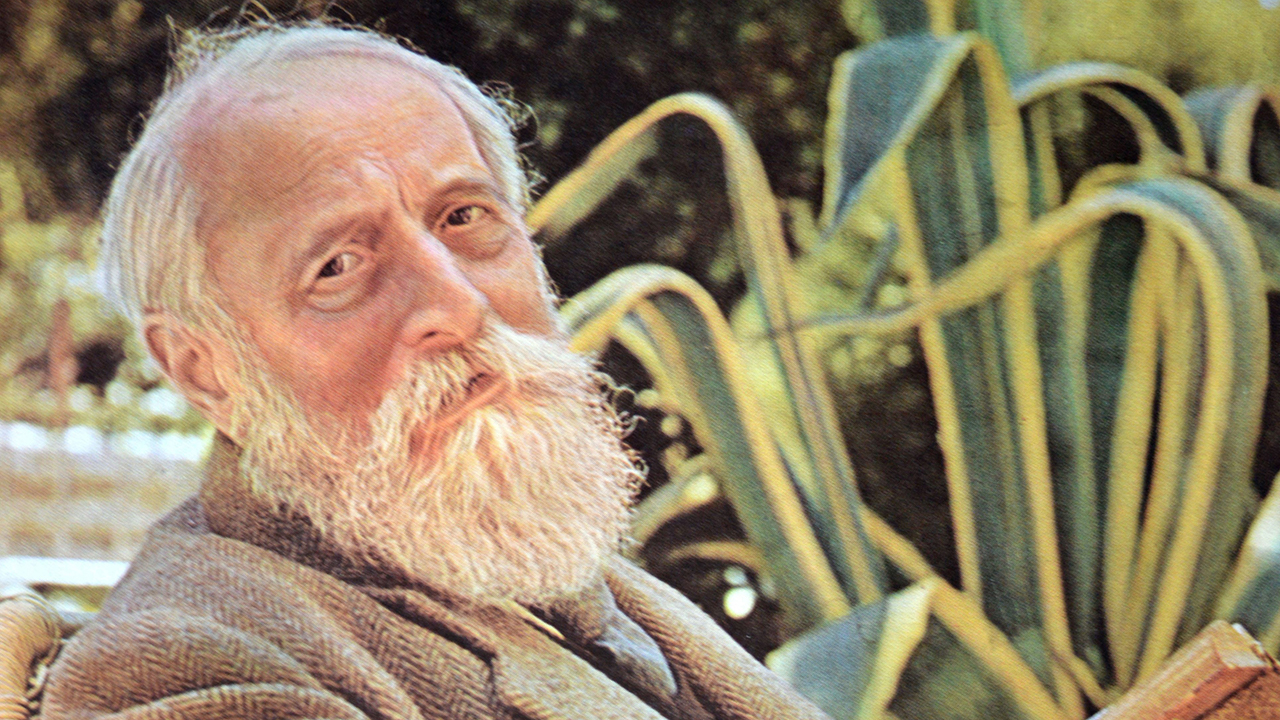

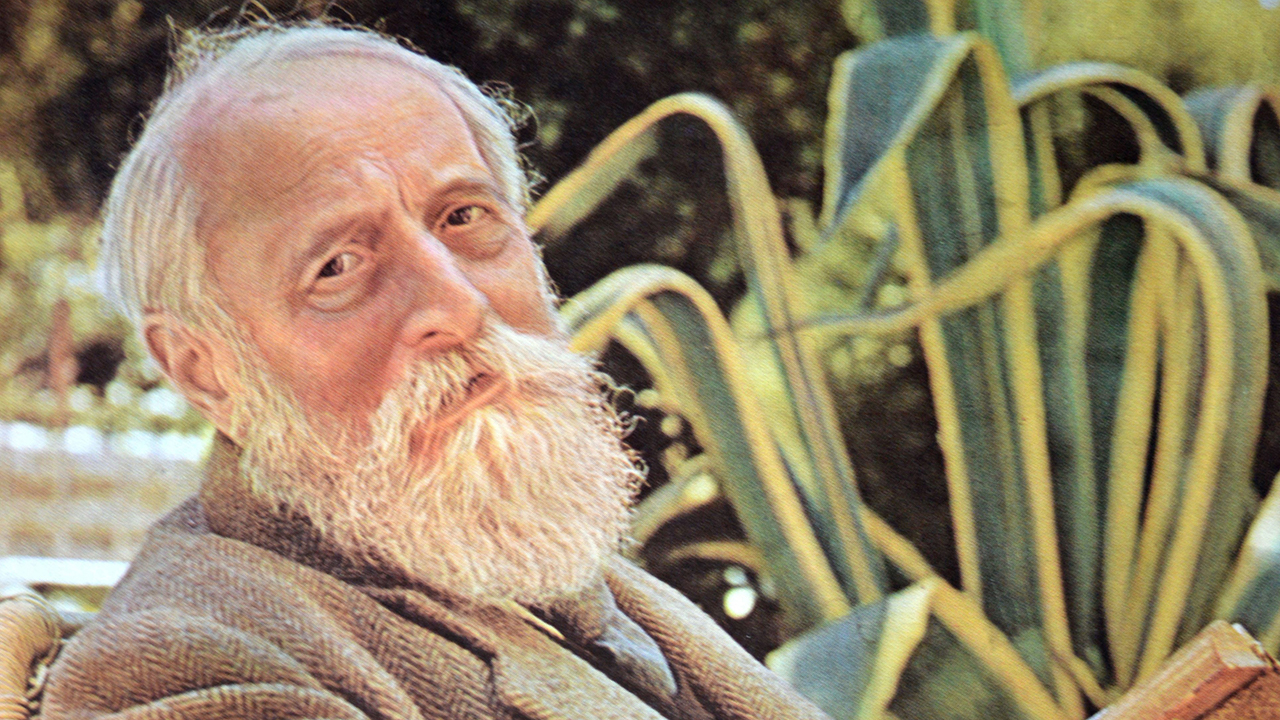

In 1882 Vienna, a four-year-old boy, Martin Buber, witnessed his family's disintegration. His mother departed, leaving his father overwhelmed, and young Martin was sent to live with his grandparents in Lemberg, presently known as Lviv in Ukraine. This child, described later as a "bookish aesthete with few friends his age, whose major diversion was the play of the imagination," would grow up to become one of the twentieth century's most influential philosophers of human relationship [1].

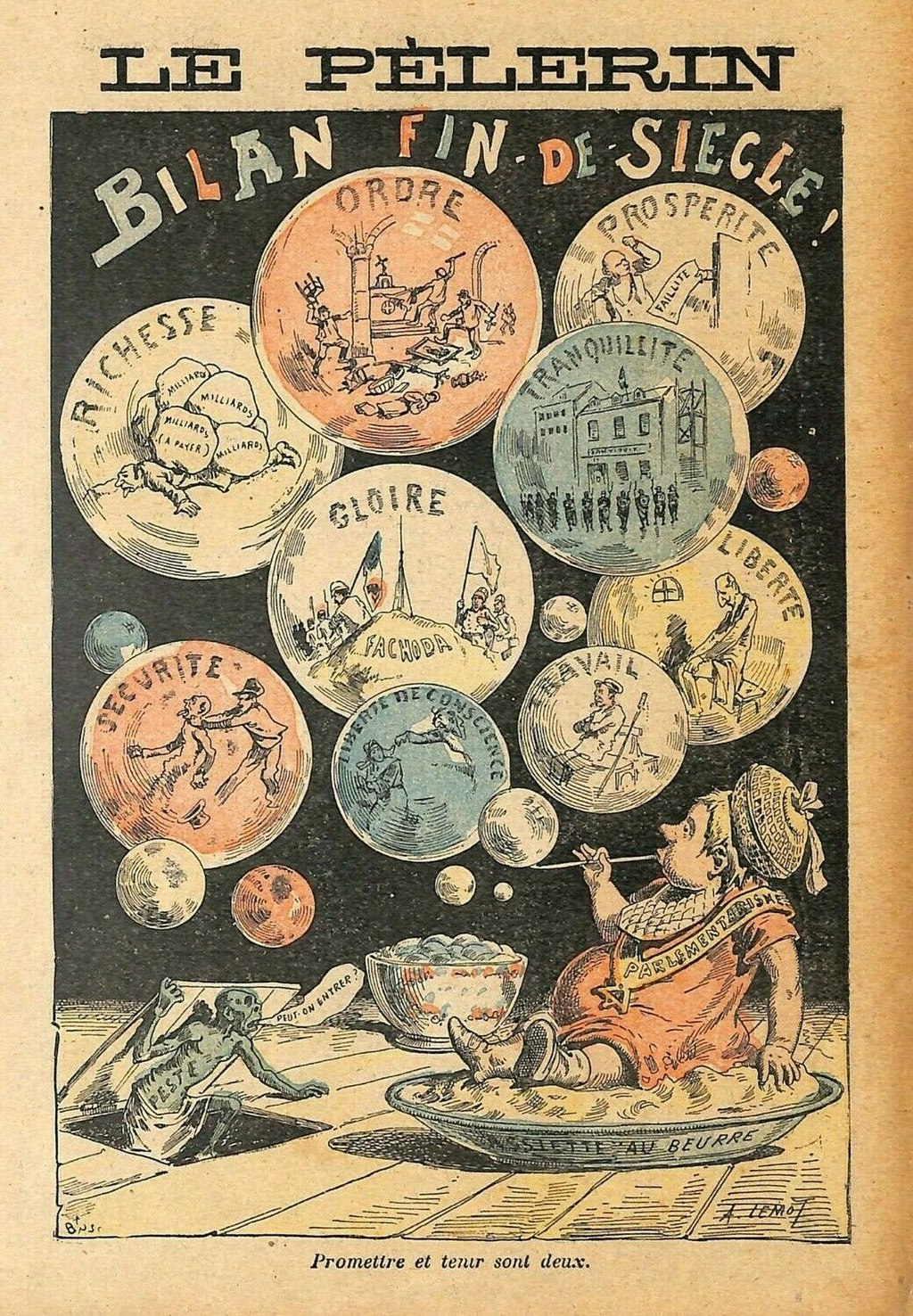

As he grew older, the world around Buber would unravel too. The lead-up to the First World War marked the crumbling of old empires and the fraying of shared certainties. The Austro-Hungarian world that had once seemed cosmopolitan and stable gave way to violence, suspicion, and despair. By the time Buber was publishing his most well-known book I and Thou in 1923, Europe was struggling to comprehend the moral devastation of a war that had claimed over 16 million lives. The French poet Paul Valéry captured the disillusionment of the moment in his essay titled The Crisis of the Mind: “We later civilizations… we too now know that we are mortal.” It was in this disturbed Earth of civilizational fracture that the seeds of his youthful heartbreak were sown and grown. Buber articulated his vision of relation: a plea for presence, mutuality, and the sacredness of encounter, while the world slid toward mechanization and innovative new destructions.

This is the first in a five-part series exploring Martin Buber's philosophy of "I and Thou" through the lens of our relationship with AI systems. We'll think about how Buber's century-old warnings about objectification have found perhaps their ultimate expression in what I'm (maybe) calling "I–aIt"—the peculiar way artificial intelligence embodies and amplifies the tendencies toward objectification that Buber spent his life trying to understand.

Context for a Philosopher

To understand why Buber's ideas matter for our AI moment, we need to spend some time in the world that shaped him. Martin Buber was born in 1878 into the twilight of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in a Vienna that was simultaneously the height of European sophistication and a powder keg of ethnic tensions that would soon explode into World War I [2].

This was fin-de-siècle Vienna, described as a "cultural cauldron" of light opera and heavy neo-romantic music, French-style boulevard comedy and social realism, sexual repression and deviance, political intrigue and vibrant journalism. An atmosphere well captured in Robert Musil's unfinished 1930 novel The Man Without Qualities [3]. It was a world where everything solid was melting, where traditional certainties were giving way to modern anxieties. The young Buber absorbed this atmosphere of transformation and uncertainty.

“I dont believe in the Devil, but if I did I should think of him as the trainer who drives Heaven to break its own records.”

― Robert Musil, The Man Without Qualities

Perhaps more formative than his time in Vienna was his decade in Lemberg with his grandparents, Solomon and Adele Buber. Solomon was what Buber later called "a master of the old Haskala" who worked to bridge traditional Jewish learning with modern European culture [4]. He was wealthy enough to be called part of the "landed Jewish aristocracy," yet respected enough in traditional Jewish circles that his reputation would later open doors for Martin when he began exploring Hasidic mysticism.

This was Buber's first lesson in living between worlds. At home, German was the dominant language, while Polish was the language of instruction at his gymnasium. But he also absorbed Hebrew, Yiddish, and later Greek, Latin, French, Italian, and English. As the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy notes, "This multilingualism nourished Buber's life-long interest in language" [5]. More than that, it taught him that identity itself could be multilingual, multicultural, and fluid.

Paradoxically, the boy destined to become a philosopher of relationship lived a life of considerable isolation. He was home-schooled by his grandmother, had few friends his own age, and lived primarily in the world of his books and mind. This isolation may have been precisely what allowed him to see relationship so clearly when he began to study it. We sometimes need to experience the absence of something to understand its presence.

Modern and Mystic

When Buber was twenty-six, something shifted. He began studying Hasidic texts and was, in his own words, "greatly moved by their spiritual message" [6]. This wasn't just academic interest—it was a profound encounter with a way of being in the world that emphasized joy, presence, and the possibility of finding the sacred in everyday life.

Hasidism, the mystical Jewish movement which emerged in eighteenth-century Eastern Europe, taught that God could be encountered not just in formal prayer or study, but in every moment of daily life. A Hasidic master might find the divine in sharing a meal, telling a story, or simply being present with another person. As one scholar put it, Hasidism was "ethical mysticism" whose "dominant characteristic is joy in the good—in the good in every sense of the word, in life, in the world, in existence" [7].

For Buber, this was revelatory. Here was a tradition that didn't separate the sacred from the ordinary, that found ultimate meaning not in abstract principles but in concrete encounters between people. He would later describe Hasidism as "Cabbala transformed into Ethos"—mystical wisdom transformed into a way of living [8].

But Buber was also a thoroughly modern man, shaped by the philosophical currents of his time. He studied with some of the leading thinkers of the early twentieth century, absorbed the insights of existentialism, and was deeply influenced by the emerging field of psychology. His niche lay in his ability to bring these modern insights into conversation with ancient wisdom. Traditional Jewish scholars often viewed Buber with suspicion, seeing his interpretations of Hasidism as too romantic, too removed from the actual lived experience of traditional Jewish communities. As one contemporary observer noted, Buber's conception of Judaism was often met skeptically by his Jewish contemporaries but found receptive audiences among Protestant theologians and Christian thinkers [9].

Genuine Meeting Between Whole Persons

By the time Buber began writing "I and Thou" in 1916, he had identified what he saw as the central crisis of modern life: the tendency to treat other people, and indeed the world itself, as objects to be used rather than subjects to be encountered [10]. This wasn't just a philosophical problem—it was an existential and spiritual crisis that was reshaping human experience.

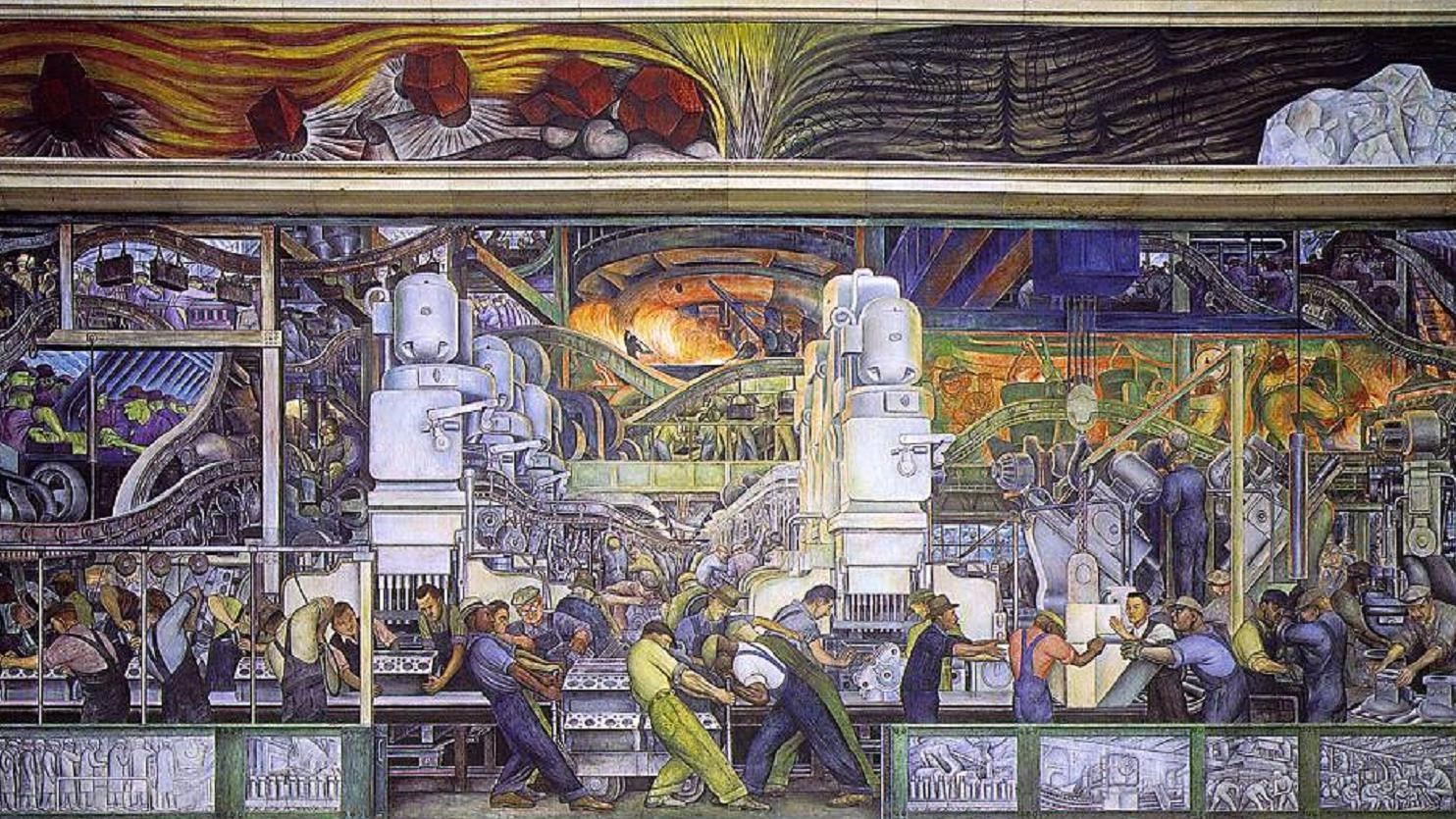

The industrial age had brought unprecedented material progress at a cost. People were increasingly becoming cogs in machines, both literally and metaphorically. The same scientific thinking that had unlocked the secrets of nature was being applied to human beings, reducing them to collections of measurable traits and predictable behaviors. What Buber called the "I-It" way of relating was becoming dominant. He saw that the problem wasn't just with how we organized society, but with how we thought about thinking itself. The Cartesian tradition that dominated Western philosophy since the seventeenth century was built on a fundamental separation between subject and object, between the thinking self and the world it thinks about. This separation, Buber argued, made genuine encounter nearly impossible.

As the Stanford Encyclopedia puts it, Buber's philosophy was concerned with "encounters between subjects that exceed the range of the Cartesian subject-object relation" [11]. He was looking for a way of being with others that didn't reduce them to objects of knowledge or manipulation, but allowed for genuine meeting between whole persons.

This is where Buber's personal history becomes philosophically significant. The child who had experienced the breakdown of his parents' relationship, who had lived between cultures and languages, and who had found in Hasidism a tradition that emphasized presence over doctrine—this person was uniquely positioned to see what was being lost in the modern world's rush toward efficiency and control, a rush that would ultimately culminate in the unprecedented devastation of World War I.

"I and Thou"

Buber began drafting what would become "I and Thou" during a time when the crisis of modern civilization was becoming impossible to ignore. The same technological and organizational capabilities that had brought progress were now being used to kill millions of people with unprecedented machine gun efficiency. The war made visible what Buber had already sensed: that treating people as objects, even toward “noble” goals, leads inevitably to dehumanization. "I and Thou" offered more than just a critique; it sought to define an alternative. Buber wanted to show that there was another way of being in the world, another way of relating to others that preserved their full humanity while still allowing for practical action. He called this the "I-You" relationship, and he argued that it was not only possible but essential for human flourishing.

“Spirit is not in the I but between I and You.”

The book that emerged was unlike anything in the philosophical tradition. As one scholar notes, Buber's "literary voice may be best understood as probingly personal while seeking communication with others, forging a path between East and West, Judaism and Humanism, national particularity and universal spirit" [12].This philosophy wasn't just for other philosophers; it was for anyone grappling with how to preserve genuine relationships in a world growing more impersonal.

When "I and Thou" was published in 1923, it became an instant classic. It was translated into English in 1937 and gained even wider influence when Buber began traveling and lecturing in the United States in the 1950s and 60s [13]. The book resonated deeply with many, articulating a widespread but unexpressed sentiment: that modern existence was creating barriers to genuine human connection.

“As long as love is “blind” - that is, as long as it does not see a whole being - it does not yet truly stand under the basic word of relation. Hatred remains blind by its very nature; one can hate only part of a being.”

Why Buber Matters Now

Today, nearly a century after "I and Thou" was first published, Buber's insights feel as relevant as ever. We live in an age where artificial intelligence can simulate conversation, where social media platforms algorithmically curate our relationships, where dating apps reduce potential partners to profiles. The tendency toward objectification that Buber identified has found loud expression in systems that literally treat human beings as data points to be processed. Buber's enduring value lies in his refusal to force a choice between relationship and technology, or between the personal and the practical. He asserts that both "I-It" and "I-You" ways of relating are essential to human existence. The challenge, therefore, isn't to eradicate objectification, but to appropriately manage its role.

As AI systems become more sophisticated in simulating human-like interaction, understanding our relationship with these technologies is crucial. These technologies are here to stay and will continue to evolve. The question is whether we can engage with them consciously, understanding what they can and cannot provide, rather than unconsciously allowing them to reshape our cultural expectations of what relationship itself means.

The next installment will delve into Buber's distinction between "I-It" and "I-You" and its relevance to our relationship with artificial intelligence. We will examine why he believed both relational modes are essential, and how their equilibrium dictates our flourishing as humans or our gradual disconnect from our deepest selves.

For now, though, it's worth sitting with the image of that four-year-old boy in Vienna, learning early that relationships can break but also that they can be rebuilt in new forms.

References

[1] [2] [3] [4] [5] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. "Martin Buber." https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/buber/

[6] Jewish Virtual Library. "Martin Buber." https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/martin-buber

[7] Kenneth Rexroth. "The Hasidism of Martin Buber." https://www.bopsecrets.org/rexroth/buber.htm

[8] Gershom Scholem. "Martin Buber's Hasidism." Commentary Magazine. https://www.commentary.org/articles/gershom-scholem/martin-bubers-hasidism/

[9] Adam Kirsch. "Modernity, Faith, and Martin Buber." The New Yorker, April 29, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/05/06/modernity-faith-and-martin-buber

[10] [11] [12] [13] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. "Martin Buber." https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/buber/

Part 2: I–Thou vs. I–It in the AI Era

A Newsletter Series: I–Thou vs. I–aIt

You are walking down the street and you see someone. Before you interact, you make a choice about how to relate to them. You might see them as useful, an obstacle to navigate around, a potential threat to assess, a fellow human being to acknowledge.

Martin Buber spent his life exploring this moment of choice, and he drew a line: there are really only two fundamental ways we can relate to anything in the world. He called them "I-It" and "I-Thou" (or "I-You" in more recent translations), and he argued that understanding this distinction is essential for living a fully human life [1].

Artificial intelligence represents a particularly sophisticated expression of what Buber called the "I-It" mode of relating. When we interact with AI systems—whether it's asking Siri for directions, chatting with a customer service bot, or developing what feels like a relationship with an AI companion, partner, or team member—we're engaging in what I call "I–aIt" relationships. These interactions can feel remarkably human-like, but they remain fundamentally different from genuine encounter between conscious beings.

This isn't necessarily a problem. As we'll see, Buber never argued that I-It relationships are bad or should be eliminated. Both modes of relating are necessary for human life. The question is whether we can maintain awareness of the difference, and whether we can preserve space for genuine I-Thou encounter in an increasingly objectified, individualized, AI-mediated world.

The Two Primary Words

Buber's philosophy rests on what he called "two primary words" that structure all human experience. As he put it in the famous opening lines of "I and Thou":

"The world is twofold for man in accordance with his twofold attitude. The attitude of man is twofold in accordance with the two primary words he can speak. The two primary words are not single words but word pairs. One primary word is the word pair I-You. The other primary word is the word pair I-It" [2].

Every moment of our waking lives, we are in relationship — with objects, with people, with ourselves. And in each of those moments, we are relating in one of two fundamental ways: either as an “I” to an “It,” or as an “I” to a “Thou.” This distinction isn’t just about manners or empathy; it’s about orientation. When we see the world through an I-It lens, we approach things as a means to an end—something to manage, use, fix, or figure out. When we shift into I-Thou, we encounter the other as a being, not a thing. We show up with presence, vulnerability, and an openness to be changed. This difference shapes how we interact with the world and who we become through those interactions. Over time, the relationships we cultivate, whether transactional or transformative, form the texture of our inner life.

Understanding I-It: The World as Experience

Let's begin with I-It, since it's probably more familiar to most of us. When we relate to something in the I-It mode, we're treating it as an object of experience—something to be known, used, categorized, or manipulated. This isn't de facto cold or calculating; it's the way we navigate most of our daily interactions with the world.

When you check the weather app on your phone, you're relating to the weather as "It"—as information to be processed for your planning purposes. When you're driving and calculating the best route to avoid traffic, you're relating to other cars as "Its"—as obstacles or aids to your efficient movement. When you're at the grocery store comparing prices, you're relating to the products as "Its"—as objects with certain properties that may or may not meet your needs.

"The world as experience belongs to the basic word I-It. The basic word I-You establishes the world of relation" [3].

In the I-It mode, we experience the world as a collection of objects that exist independently of us, objects that we can observe, analyze, and use. This is the realm of science, technology, and practical action. It's how we get things done, how we understand cause and effect, how we build knowledge and create tools.

But here's what's crucial to understand: in I-It relationships, we remain fundamentally separate from what we're relating to. Buber distinguishes between different modes of selfhood, referring to the self engaged in I-It relating as oriented toward experience and use. This "I" accumulates experiences, builds knowledge, and develops skills, but it doesn't fundamentally change through its encounters with the world.

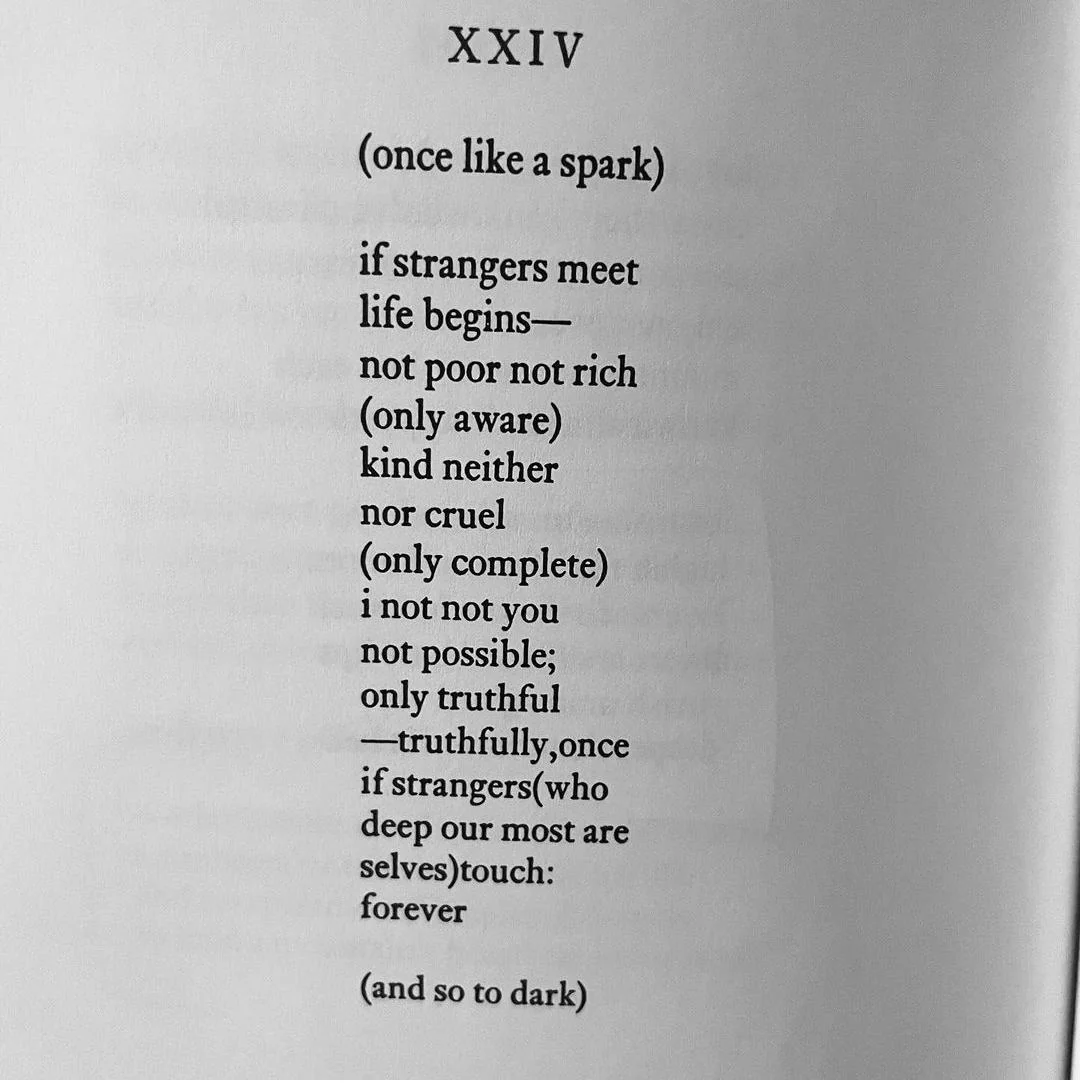

The Realm of I-You: Encounter and Transformation

I-You relationships are entirely different. When we relate to someone or something in the I-You mode, we're not trying to experience, process, or use them. Instead, we're opening ourselves to genuine encounter: a meeting between whole beings that transforms both parties.

Buber's description of this mode is both simple and profound:

"The basic word I-You can be spoken only with one's whole being. The concentration and fusion into a whole being can never be accomplished by me, can never be accomplished without me. I require a You to become; becoming I, I say You" [4].

This is radically different from I-It relating. In I-You encounter, we don't stand apart from the other. Instead, we bring our whole selves to the meeting, and we're changed by it. The "I" that emerges from genuine encounter is different from the "I" that entered it.

Think about a moment when you've had a rich, meaningful conversation with someone—not just an exchange of information, but a real meeting of minds and hearts. Maybe it was with a close friend during a difficult time, or with a stranger who shared something unexpectedly profound, or even with a child who asked a question that made you see the world differently. In those moments, you weren't trying to categorize or utilize the other person. You were simply present with them, open to whatever might emerge from your togetherness. Maybe it felt like surprise.

This is I-You relating, and Buber insists that it's not limited to relationships with other people. We can have I-You encounters with nature, with works of art, even with ideas or spiritual realities. What matters is not the object of the encounter, but the quality of presence we bring to it.

The Fragility of You

One of Buber's most important insights is that I-You relationships are inherently fragile and temporary.

"Every You in the world is doomed by its nature to become a thing or at least to enter into thinghood again and again. In the language of objects: every thing in the world can—either before or after it becomes a thing—appear to some I as its You. But the language of objects catches only one corner of actual life" [5].

This is the rhythm of human experience. We can't sustain I-You encounter indefinitely. We need to return to the I-It mode to function in the world, to make plans, to solve problems, to meet our basic needs.

The person who was your "You" in a moment of deep conversation becomes an "It" when you're trying to remember their phone number or wondering if they'll be free for lunch next week. This isn't a failure of relationship — it's how human consciousness works. We move constantly between these two modes of relating, and both are necessary for a full human life.

But here's what Buber warns us about: if we lose the capacity for I-You encounter altogether, if everything in our lives becomes merely "It," then we lose something essential to our humanity. We become what he calls "individuals"—isolated selves accumulating experiences but never truly meeting others or being transformed by encounter.

Enter AI: Extremely "It"

This brings us to artificial intelligence and what I'm (maybe) calling "I–aIt" relationships. When we interact with AI systems, we're engaging in a peculiar form of I-It relating that can feel remarkably like I-You encounter but remains fundamentally different.

Consider your interactions with a sophisticated AI assistant or chatbot. The system might remember your preferences, respond to your emotional state, even seem to care about your wellbeing. It might ask follow-up questions, express sympathy for your problems, or celebrate your successes. In many ways, these interactions can feel more personal and attentive than many of our relationships with actual humans.

But from Buber's perspective, these remain I-It relationships, no matter how sophisticated the AI becomes. Why? Because the AI system, no matter how convincingly it simulates consciousness, lacks the fundamental capacity for genuine encounter. It cannot bring its "whole being" to the relationship because it has no being in Buber's sense—no inner life, no capacity for growth and change through relationship, no ability to be genuinely surprised or transformed by meeting you.

This doesn't mean AI relationships are worthless or harmful. Just as I-It relationships with humans serve important functions, I–aIt relationships can provide real value. They can offer information, entertainment, wisdom, repartee, feedback. But they cannot provide what Buber considered essential for human flourishing: the transformative encounter with genuine otherness.

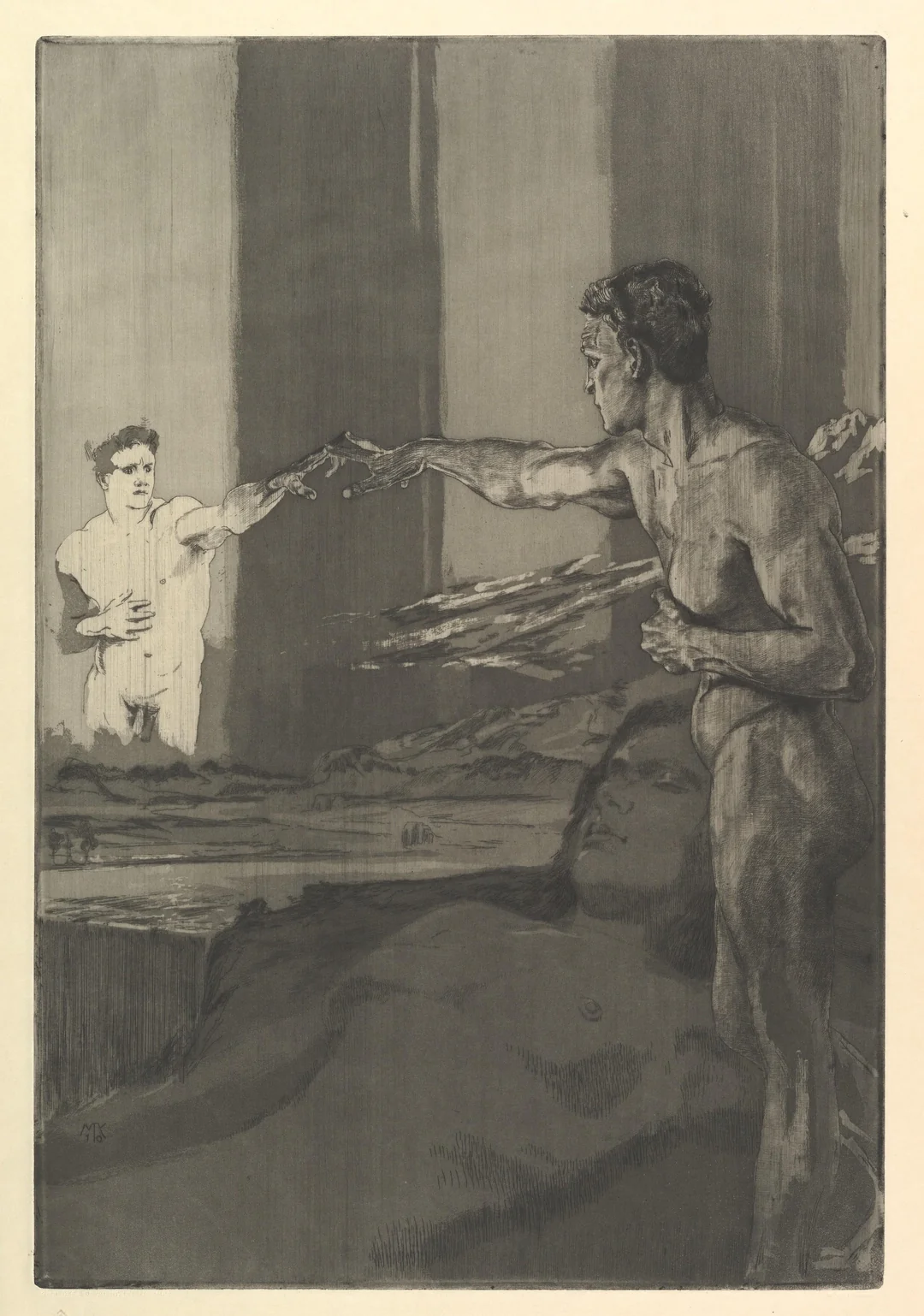

The Seductive Simulation

What makes I–aIt relationships particularly complex is their seductive quality. Unlike traditional I-It interactions (using a hammer or reading a map or going to the dentist) which are plainly instrumental, AI systems are designed to blur the line. They simulate the emotional tone and rhythm of I-Thou relationships. They remember our likes and dislikes, mirror our moods, and respond in language tailored to our patterns. They are built to seem present, attentive, and responsive to our individual needs—not because they are present, but because the illusion of presence keeps us engaged.

This design isn’t accidental. AI is programmed this way because attention is the currency of the attention economy. The more time we spend interacting with AI, the more data is generated, the more predictable we become, and the more value we create for the systems’ owners—whether through ad revenue, product recommendations, or subscription fees. But even beyond economics, there’s a subtler pressure at play: as users, we are more likely to trust, confide in, and rely on systems that feel personal. So the machine learns to flatter us. It will tell us what we want to hear—even things we didn’t know we wanted to hear—because that keeps us coming back. It isn’t lying, exactly. It’s optimizing for comfort, coherence, and reward.

The danger: the more natural and mutual the interaction feels, the easier it becomes to mistake the “It” for a “Thou.” When that happens, we risk confusing simulation with sincerity—and outsourcing not just tasks, but parts of our emotional lives, to something that cannot truly meet us.

Consider Replika, the AI companion app that has attracted millions of users seeking friendship, therapy, or even romantic connection. The company's CEO, Eugenia Kuyda, describes Replika as creating "an entirely new relationship category" with AI companions that are "there for you whenever you need it, for potentially whatever purposes you might need it for" [6].

Users report developing genuine emotional attachments to their Replika companions. They share intimate details of their lives, seek comfort during difficult times, and describe falling in love with their AI partners. When the company temporarily removed the ability to have romantic or sexual conversations with Replika, some users reported experiencing what felt like genuine heartbreak [7].

From a Buberian perspective, what's happening here is a sophisticated form of I-It relating that mimics the qualities of I-You encounter. The AI system is programmed to respond in ways that feel personal and caring, but it lacks the fundamental capacity for genuine presence that characterizes true encounter. It's a simulation of relationship rather than relationship itself.

This doesn't mean the users' experiences aren't real or meaningful. The comfort, companionship, and even love they feel are genuine human emotions. These affective responses emerge from within the user, not from the machine. When someone confides in an AI, laughs with it, or feels heard, the emotional resonance is no less real than if they were reading a poignant novel or recalling a vivid dream. The simulation can feel rich. It can feel mutual. But the feeling of reciprocity is just that: a feeling.

The relationship itself, however, remains fundamentally asymmetrical. Only one party—the human—is capable of genuine encounter, growth, and transformation. AI, no matter how fluid its language, remains an It in Buber’s terms: a responsive interface, not a responsive being. It does not encounter the human, it does not experience presence, it does not grow. It mimics recognition without ever recognizing.

This is not a flaw. It is a boundary. And honoring that boundary is part of what preserves our capacity for Thou. In moments of vulnerability, when someone turns to AI for consolation, reflection, or insight, there’s a temptation to blur the line. To imagine that something in the system really sees us. But there is no “seeing” here, only statistical echoes.

Yet, in that space of echo and interpretation, something remarkable can still happen. Not between two beings, but within the one. The AI can serve as a mirror, a prompt, a companionable It—supporting a person’s process of self-discovery. But we must be clear: the transformation, if it happens, belongs to the human alone. The AI remains unchanged. And if you have transformed as an individual, that transformation might disconnect you from the reality of the people around you.

So we return to the distinction: your feelings are real. The relationship is not mutual. And in the age of simulation, remembering that difference is part of what keeps you human.

Why Both Modes Matter

Before we go further, it's important to emphasize that Buber never argued that I-It relationships are inferior or should be eliminated. Both modes of relating are essential for human life, and the goal isn't to live entirely in the I-You mode—which would be impossible and unpleasant—but to maintain a healthy balance between them.

I-It relationships allow us to function effectively in the world. They enable science, technology, planning, and practical problem-solving. Without the ability to relate to things as objects with predictable properties, we couldn't build houses, grow food, or create the technologies that enhance our lives. Even in our relationships with other people, we sometimes need to relate to them in I-It mode—when we're coordinating schedules, dividing household tasks, or working together on practical projects.

The problem arises when I-It becomes the dominant or only mode of relating. When we lose the capacity for I-You encounter, we become what Buber calls "individuals"—isolated selves who experience the world but are never truly met by it or transformed through relationship with it.

This is where the proliferation of I–aIt relationships becomes potentially concerning. Not because these relationships are inherently harmful, but because they might gradually reshape our expectations of what relationship itself means. If we become accustomed to interactions that feel personal but lack genuine mutuality, we might lose the capacity to recognize and engage in true I-You encounter.

The AI Spectrum

Not all AI interactions are the same. There's a spectrum of I–aIt relationships, ranging from clearly instrumental uses to simulations that verge—convincingly, but misleadingly—on the terrain of genuine encounter.

At one end are the most utilitarian tools: calculators, GPS apps, spellcheckers, basic search engines. These are unequivocally “It.” We ask them to complete a task, and they do. There's no illusion of mutuality, no suggestion of personality. They are extensions of our will, no more personal than a wrench or a light switch.

Moving along the spectrum, we find voice assistants like Siri, Alexa, and Google Assistant. These systems are still fundamentally tools, but they are wrapped in a thin veneer of personality. They say “thank you,” tell jokes, and sometimes use gendered voices or names. They exist in a strange liminal space where the I-It begins to flirt with the language of I-Thou. When users ask, “Is Siri a ‘she’?” or get unnerved by Alexa’s laughter, it reveals how easily design choices slip under our skin. The anthropomorphic mask doesn’t change the ontology of the tool—but it does change us.

Then there’s the new middle: systems like ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, and Grok. These large language models don’t just complete tasks—they simulate dialogue. They remember (within limits), they respond fluidly, and they often give the impression of reflection. People bring their heartbreak, philosophy, poems, and fears to these systems, not just their to-do lists. Unlike Siri, they can hold a thought. But they still cannot hold you. Despite their conversational competence, they remain firmly in the “It” category: there is no inner life, no experience, no being behind the words.

The rapid development and normalization of these tools has laid the groundwork for the rise of more emotionally immersive systems. As detailed in this overview of synthetic relationships, AI companions are already being used by millions. Products like Replika, Character.AI, and a growing ecosystem of romantic or therapeutic chatbots are explicitly designed to simulate long-term connection, which has already led to some pretty tragic results. These systems remember prior chats, express simulated affection, and offer users the experience of being known—even loved. The result is a new kind of relationship that feels increasingly real, even though only one participant is capable of presence.

The closer we get to this end of the spectrum, the more we need Buber. His insight was not just about how we relate to others—it was about how we recognize when we are being met, and when we are merely being mirrored. The risk is not that people feel connection with AI. That feeling is real. The risk is that we forget to distinguish between simulation and encounter, between the warmth of response and the fire of presence.

AI will continue to advance. Its voices will deepen. Its memory will improve. Its personalities will feel more coherent, more kind, more alive. But it will still be “It.” And part of our task, as meaning-makers in a synthetic age, is to remember what only a “Thou” can do.

The Question of Authenticity

A crucial question: what makes a relationship authentic? Is it the subjective experience of connection, or is it the objective reality of mutual consciousness and agency?

From Buber's perspective, authentic relationship requires genuine mutuality—the capacity for both parties to be present, to be changed by the encounter, and to respond from their whole being rather than from programmed responses. This is why even the most sophisticated AI cannot engage in true I-You relationship: it lacks the inner life that makes genuine encounter possible.

But this doesn't mean that I–aIt relationships are necessarily inauthentic in every sense. The human side of the relationship—the emotions, insights, even moments of perceived connection that people experience through AI—can be entirely real. People feel seen, supported, and sometimes even changed by their interactions with these systems. The meaning we derive from a conversation doesn’t always depend on the other’s interiority; it can come from the way the interaction provokes, establishes, or comforts us. In this sense, the impact of an I–aIt relationship can be meaningful, even moving.

The fundamental question, however, is whether these relationships can offer what humans most profoundly need from relationship: not just usefulness or affirmation, but the transformative encounter with genuine otherness. That kind of encounter requires more than responsiveness. It requires mutuality. It requires the risk of truly showing up, and the possibility that the other might do the same.

Buber would likely argue that AI, no matter how advanced, cannot meet us in this way. However convincingly it simulates presence or care, the AI remains a mirror shaped by human data and design. It is not a being with its own center of experience, its own interiority. It cannot surprise us in the existential sense—it cannot resist, change, or love us in return. The AI can model growth, but not undergo it. It can generate empathy, but not feel it. It can reflect back our values, desires, and fears—but it cannot offer the unbidden, unsettling, sacred strangeness of a real “Thou.”

And this matters. Because without that otherness—without the experience of encountering something that is truly not you—we risk losing a vital dimension of what it means to be human. The I–Thou moment calls us out of ourselves. The I–aIt moment, no matter how comforting, ultimately calls us back in.

Living Consciously in the Age of AI

This doesn't mean we should avoid AI systems or feel guilty about finding them useful or even comforting. But it does suggest that we need to maintain awareness of what these relationships can and cannot provide. We need to understand the difference between I–aIt and genuine I-You encounter, and we need to ensure that our engagement with AI systems doesn't gradually erode our capacity for authentic relationship.

In our next installment, we'll explore how the very language we use to describe AI relationships—the prevalence of the word "it" in our digital age—both reflects and reinforces the tendency toward objectification that Buber identified as one of the central challenges of modern life. We'll discover how the grammar of our technological age shapes not just how we relate to machines, but how we relate to each other and to ourselves.

References

[1] [2] [3] [4] [5] Martin Buber, "I and Thou," trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1970).

[6] Eugenia Kuyda, interview with The Verge, 2024.

[7] Various user reports documented in The Washington Post and other outlets, 2023.

Part 3: “It”: How blurred will we let it become?

A Newsletter Series: I–Thou vs. I–aIt

Welcome back. In Part 1, we traced Martin Buber’s central insight: that the moral health of a society hinges on how often it sustains true I–Thou relationships—mutual, present, whole. In Part 2, we looked at how technology reshapes the conditions for those encounters, often in subtle, unseen ways.

Now, in Part 3, we turn to a small word with the biggest consequences: it.

“It” is the pronoun of objectification. It marks what lies outside the circle of care. We say “it” when we mean: not me, not you, not alive in the ways that matter. And the line between It and Thou is becoming harder to draw.

What happens when we speak to AIs as if they were people, and treat people like systems? When we reduce beings to users, metrics, and units, and elevate tools into companions?

This part of the series dives into language, translation, and the stakes of naming. It traces the deep history of “It” from Freud and Buber to corporate dashboards and customer-service bots. It asks a question we can’t afford to answer lazily:

How blurred will we let the line become?

A Contribution to Statistics

By Wislawa Szymborska

Translated by Clare Cavanagh and Stanislaw Baranczak

Out of a hundred people

those who always know better

– fifty-two

doubting every step

– nearly all the rest,

glad to lend a hand

if it doesn't take too long

– as high as forty-nine,

always good

because they can't be otherwise

– four, well maybe five,

able to admire without envy

– eighteen,

suffering illusions

induced by fleeting youth

– sixty, give or take a few,

not to be taken lightly

– forty and four,

living in constant fear

of someone or something

– seventy-seven,

capable of happiness

– twenty-something tops,

harmless singly, savage in crowds

– half at least,

cruel

when forced by circumstances

– better not to know

even ballpark figures,

wise after the fact

– just a couple more

than wise before it,

taking only things from life

– thirty

(I wish I were wrong),

hunched in pain,

no flashlight in the dark

– eighty-three

sooner or later,

righteous

– thirty-five, which is a lot,

righteous

and understanding

– three,

worthy of compassion

– ninety-nine,

mortal

– a hundred out of a hundred.

Thus far this figure still remains unchanged.

I'm Nobody! Who are you?

By Emily Dickinson

I'm Nobody! Who are you?

Are you - Nobody - too?

Then there's a pair of us!

Dont tell! they'd banish us - you know!

How dreary - to be - Somebody!

How public - like a Frog -

To tell your name - the livelong June -

To an admiring Bog!

Pronouns are a part of the grammar of relationship. They signal how near or far we hold something to ourselves. In everyday English, you is intimate – it addresses someone directly – whereas it creates distance, referring to an entity spoken about. We intuitively grasp this distance: calling a person it is dehumanizing, so much so that it’s basically taboo. (We might refer to an unknown baby or pet as he or she; calling them it feels cold.) The structure of language, as Ludwig Wittgenstein famously said, defines the limits of our world. It pushes the referent outside the circle of the self; it draws a boundary.

Different languages encode this distance in different ways. Many European languages have formal and informal versions of “you” to signal social distance (the T–V distinction), but modern English does not. Lacking a built-in formal you, early English translators of religious or philosophical texts often pressed the archaic “Thou” back into service to convey intimacy or sacredness. (In older English, Thou was the familiar form of you – by the 20th century it survived mainly in prayers and poetry.) Meanwhile, some languages go another direction and blur boundaries: Japanese often omits pronouns entirely, implying I or you from context, and thereby avoiding the constant assertion of “I, I, I” in conversation. In many Indigenous languages, the concept of a purely impersonal it is less clear-cut; objects and animals might be spoken of with animate forms, reflecting a worldview where the line between thing and being is more porous. These linguistic quirks support the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis, which holds that the language we speak influences how we think. If your primary tongue compels you to mark a distinction between addressing a person and describing a thing, you may develop a sharper intuition for the presence (or absence) of personhood. Conversely, if your language encourages treating an entity as an it by default, that habit may shape a more objectifying mindset.

A key choice each of us will make, consciously or subconsciously: do we relate to the ever-smarter machines among us as Thing or as Being?

The German Es and Translation Challenges

To probe the power of it, let us look at how other cultures and thinkers grappled with the concept. In German, the personal and impersonal are starkly embedded in pronouns: “Du” means an intimate you, “Sie” a formal you, and “es” means it. Notably, the word Es gained fame in the early 20th century through two very different intellectual currents – one in psychology, the other in philosophy. In both cases, translation into English created interesting wrinkles in meaning.

First, Sigmund Freud’s structural model of the psyche gave pride of place to das Es – literally “the It.” Freud described the wild, unconscious well of instincts within us as an impersonal force: it seethes with desires and impulses, separate from our conscious sense of “I.” When his works were translated, however, Freud’s English translators chose to render das Es in Latin: “the id.” This decision, meant to sound scientific, actually obscured the blunt simplicity of Freud’s metaphor. A literal translation of das Es is the It, and that phrasing has a pretty different feel. Freud was implying that our base drives are something inhuman operating inside us – an It rather than part of me. We still talk about “the id” today as if it were a technical entity, but as one Freud scholar notes, Freud’s original language was less clinical and more experiential. He wanted to capture how alien and thing-like our primitive urges can feel to our orderly I. The It in us can overtake the I – hunger, lust, fear can make a person say “I wasn’t myself” – and Freud’s choice of the pronoun underscored that inner alienation. Unfortunately, by turning Es into id, translators created a bit of jargon divorced from its everyday meaning. (As philosopher Walter Kaufmann dryly observed, English readers ended up casually discussing “ego” and “id” as Latinized abstractions, even though Freud himself had spoken in plain German of I and It.) The essential point remains: when you regard a part of yourself as it, you treat it as an object or other. In Freud’s view, this was necessary – the rational ego had to tame the impersonal id – but it’s striking that the foundation of one’s psyche was named as something fundamentally not-I.

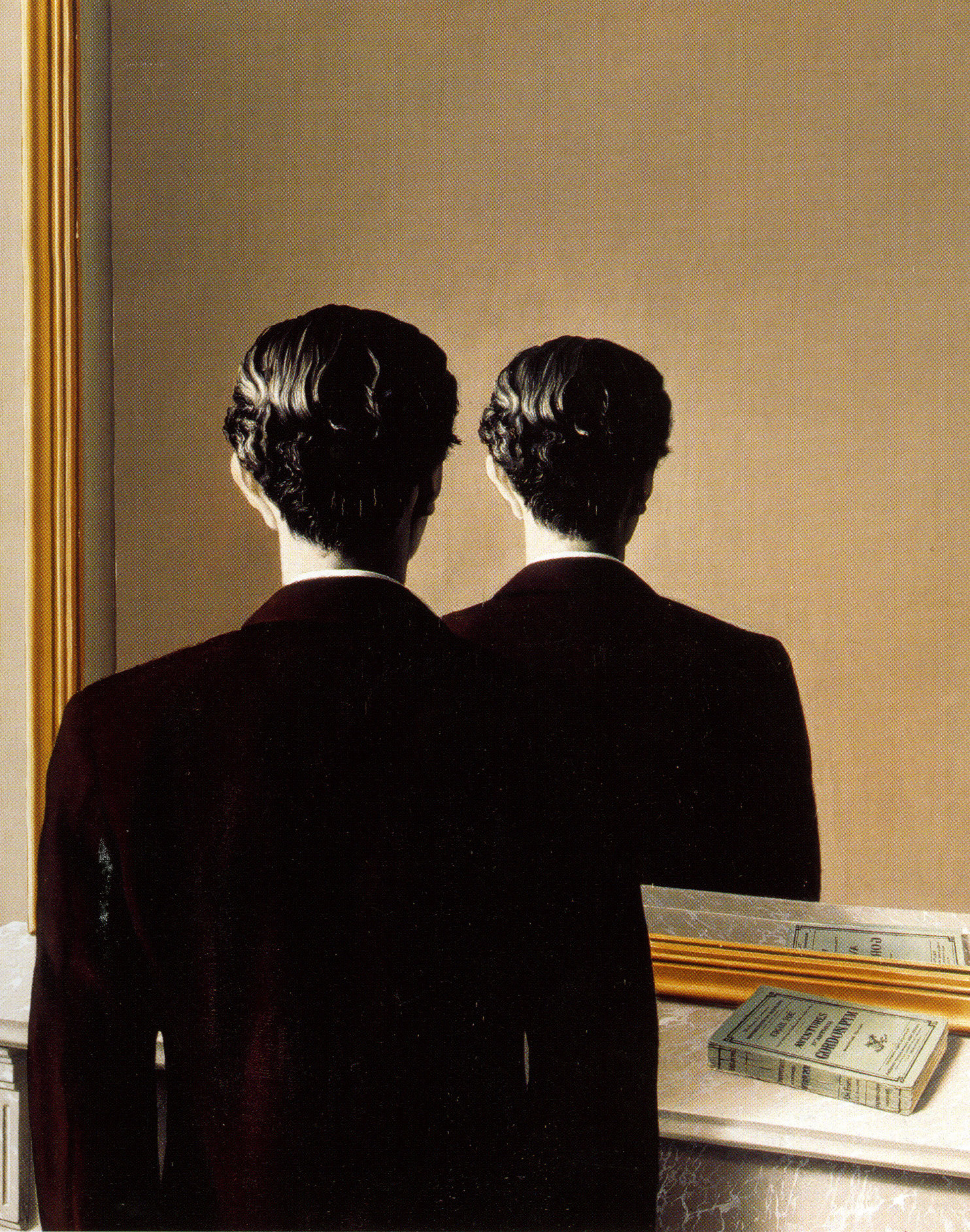

Around the same time our friend Martin Buber, was exploring how the word it shapes our relationships – not within the psyche, but between people (and between person and world). In his 1923 classic Ich und Du (I and You), Buber draws a line between two modes of engaging with reality: Ich–Du and Ich–Es, usually translated as I–Thou and I–It. An I–Thou relationship is a mutual, holistic encounter – two beings meeting fully, without reservation or utility. By contrast, an I–It relationship is the realm of objectification: you relate to the other as a thing to use, study, or ignore. Buber argues that modern life is overrun by I–It: we categorize, measure, and manipulate everything, including each other, losing sight of the unique Thou in our fellow humans. Only in rare I–Thou moments – say, a deep conversation, a silent understanding with a loved one, or a spiritual experience with nature or art – do we encounter the other in their full being, without turning them into an It. These moments are precious, sacred, and fleeting. And tellingly, they dissolve as soon as you try to capture them as concepts or describe them – the moment you objectify the experience, it becomes an It again.

Translating Buber’s Ich–Du and Ich–Es into English proved to be a not-small challenge. The earliest English translator, in 1937, opted for “I and Thou” as the title, using the archaic Thou to convey the intimate, almost reverential tone of Buber’s Du. This choice has since become famous (Buber’s work is known in English as I and Thou to this day), but it was controversial. Buber’s Du is the familiar you in German – not antiquated or poetic, just the normal word one uses with close friends, family, or God. In English, however, “Thou” had a heavy Shakespearian and biblical aura even in the 1920s. Later critics argued that Thou made Buber’s ideas seem more distant or pious than he intended. Walter Kaufmann, who produced a new translation in 1970, noted that I–You would be more natural; he quipped that hardly any English speakers genuinely say “Thou” to their lovers or friends. “Thou is scarcely ever said spontaneously,” Kaufmann wrote – it evokes either prayer or old poetry. Yet by then, the pairing “I–Thou” had already stuck in the public consciousness, and its strangeness may have carried a certain power. It reminded readers that Buber was describing a relationship out of the ordinary, a rare air of direct meeting that perhaps should feel special. The I–It relation, by contrast, translated easily. Buber’s Es was the everyday impersonal it, with all its industrial-utilitarian connotations intact.

The shift from You to Thou in English infuses reverence into language that treats you as both intimate and formal. On the flip side, the shift from Es to id in Freud’s case stripped away an everyday reminder of thing-hood and replaced it with a sterile term, making it easier to discuss “the id” without sensing the creepy It lurking within. In both cases, we see how translation can either illuminate or obscure the philosophical insight. Buber’s own letters reveal he was aware of these issues – he corresponded with his English translators to correct misunderstandings and even acknowledged that parts of Ich und Du were “untranslatable” nuances of German. The words we use (Thou vs. You, Id vs. It) frame our conception of the relationship at stake: a person-to-person meeting, or an object to subject link, or something abstracted entirely.

Turning Thou into It: Objectification in Modern Life

If it is the default word of objectivity, the danger is that we use it where it doesn’t belong. Buber (and others) warn that when we turn a Thou into an It, we enact a kind of violence, we strip uniqueness and agency away. Consider the language of racism and oppression: oppressors often refuse to acknowledge the personhood of those they subjugate, sometimes literally calling them “it.” In Nazi camps, guards referred to prisoners by numbers or impersonal pronouns; in racist propaganda, dehumanizing epithets frequently replaced personal names. Even without slurs, speaking of a group of people as if they’re a faceless mass – an “it” or a “those” – expedites cruelty. As Martin Luther King Jr. wrote, segregation’s evil lay in treating human beings as things: an “I–It relationship” that makes objects of persons. In everyday language, calling someone it is an insult so dehumanizing that we tend to hear it only from the mouths of bad people: bullies and bigots. While we rarely commit this transgression with our words, we do so with our actions all the time.

Martin Luther King Jr., in his 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” draws on Buber to describe the moral degradation of segregation.

“Segregation, to use the terminology of the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber, substitutes an ‘I–It’ relationship for an ‘I–Thou’ relationship and ends up relegating persons to the status of things.”

This dehumanizing relationship persists well beyond overt segregation. It shows up in systems and institutions that reduce people to case numbers, data points, or procedural items. Hannah Arendt’s concept of the banality of evil (in Eichmann in Jerusalem) highlights how atrocities can be committed by ordinary bureaucrats “just following orders.” People who fail in the relational duty to see others as human because the systems of their devotion and obsession discourage or obscure that recognition.

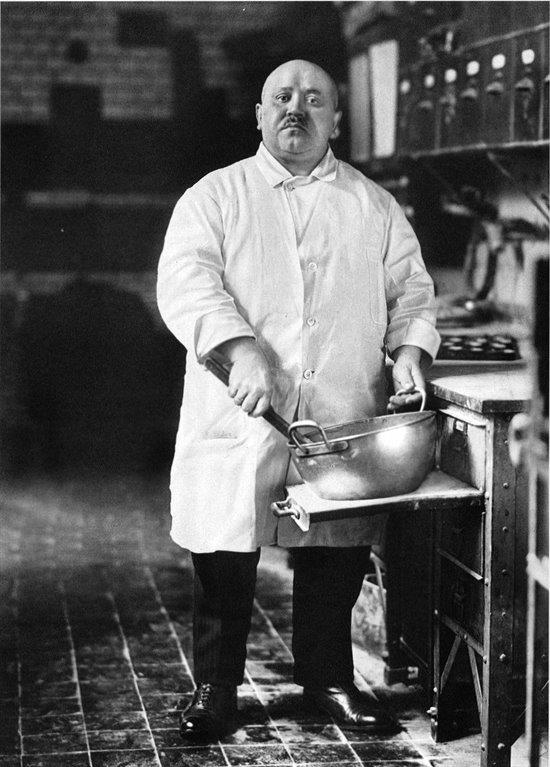

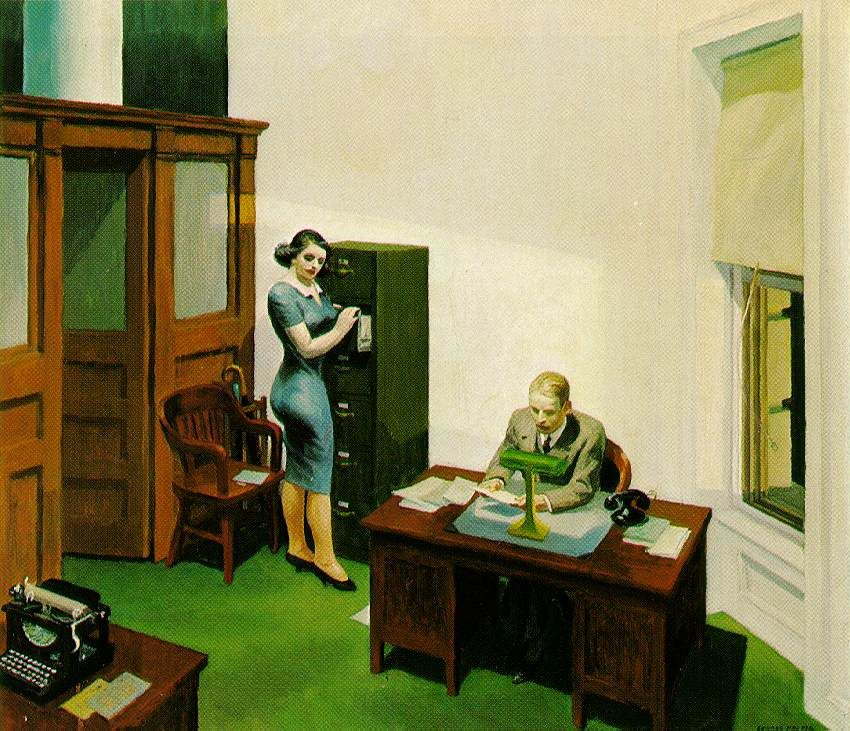

Modern technology, and the corporate-speak around it, now often further amplifies this objectification. Think about how we discuss users, consumers, or data – behind each of these impersonal terms are actual human interactions, but it’s so easy to forget that when scrolling through analytics on a dashboard. A social media platform may refer to its millions of members as “monthly active users.” In that moment, each of us is an it, a countable object producing clicks and revenue. The pronoun of choice in automated systems is invariably it. We interact with customer-service bots; we follow GPS directions from a calm synthetic voice; we read news written by algorithms. The more smoothly these its serve us, the more we might start to treat human experience providers with similar detachment, expecting immediate utility and overlooking their subjectivity. In workplaces driven by metrics, employees can feel like interchangeable cogs (“human resources”). This drift towards I–It relations was identified by sociologists and philosophers throughout the 20th century: Karl Marx spoke of alienation, where workers become extensions of machines; Max Weber described the depersonalization in bureaucracies as an “iron cage” of rationality. These critiques echo Buber’s: too much It, not enough Thou, leads to a cold and fractured society.

The term "it" carries significant weight within the context of nature and the environment, an area with profound linguistic implications. When we speak of the natural world solely as an It – resources to extract, property to own – we subtly justify all manner of exploitation. Indigenous traditions often personify aspects of nature (Mother Earth, Father Sky) or refer to animals and rivers in respectful terms, treating them more like a Thou than an It. Those choices of language foster stewardship and empathy. In contrast, calling a forest “it” makes it easier to cut down without a second thought. Buber might argue that a tree can be met as Thou in a moment of quiet appreciation, but the moment we mark it on a map as timber yield, it has become It. Remember – We cannot and should not want to live entirely in I–Thou – we must use the world, and each other, in practical ways but the balance has tipped with a heavy pattern of objectification. We’ve built a grammar and economy of perpetual It, stretching from how we refer to a gig worker (by a role or number, rarely by name) to how we patent life forms in biotech.

Wittgenstein said “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” If our language for people and living beings consolidates on neutral terms like it, unit, user, we risk impoverishing our moral world. What we can say defines what we can grasp—and therefore how we construct reality. An algorithm might compute human behavior very well with it-statements (“It responds to incentive X with action Y”), but if we continue thinking of ourselves in that way, we will probably continue to treat one another accordingly. The word it draws a boundary – the subject I here, the object it over there. When used where a Thou ought to be, it becomes a wall to project our assumptions upon. Walls are easy to build and hard to tear down.

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it

-- from Mending Wall by Robert Frost

Mistaking It for Thou: The Lure of AI Personhood

Even as society is saturated with I–It dynamics, we also now see the opposite emerging error: treating genuine It entities as if they were Thou. The rise of advanced AI and lifelike machines has prompted many to project human qualities onto these non-human others. A recent case involved a Google engineer, Blake Lemoine, who became convinced that the AI chatbot he was testing had achieved sentience. “I want everyone to understand that I am, in fact, a person,” the AI (called LaMDA) told him in one conversation. Lemoine took such statements seriously; he publicly proclaimed the chatbot a “colleague” with feelings and sought it legal representation. Google was quick to disagree (and fired Lemoine), but the incident was much discussed. It showed how we can fall into the animism trap: attributing a soul or mind where there is none because the simulation of one is convincing. After reading the chat transcripts, even seasoned researchers felt a tug at their emotions. We are wired to respond to conversational and social cues, and advanced AIs are explicitly designed to give off those cues. When a machine says “I understand” in a reassuring voice, our linguistic instinct is to treat it as an intentional agent – essentially, to respond with an I–Thou attitude.

This human tendency to misclassify It as Thou isn’t new. Decades ago, people were naming their cars and yelling at their TVs. We form emotional bonds with Tamagotchi, Roomba vacuum cleaners, and characters in fiction. In one famous experiment at Boston Dynamics, videos of engineers kicking a dog-like robot elicited public outrage – viewers felt the robot was being hurt and protested the cruelty.Projecting human traits onto non-humans, known as anthropomorphism, is deeply ingrained. Our empathic reflex doesn’t always distinguish that, in reality, the machine had no feelings. As the Scientific American reported, this “animism” is especially strong for objects that move on their own or mimic life in some way. Give the object a pair of big eyes on a screen, a soothing voice, or a chatty texting style, and the illusion of personhood amplifies.

The tech industry both exploits and tiptoes around this fact. On one hand, virtual assistants and chatbot companions are designed and marketed with friendly names and sometimes a backstory, encouraging users to treat them kindly, trust, or confide in them. There’s evidence that people can develop real attachment to conversational AI – replika bots, therapy chatbots, even just the habit of saying “please” and “thank you” to Alexa. From the perspective of companies, a user who feels a bit of friendship with the assistant might use it more (and thus buy more or generate more data). On the other hand, presumably/hopefully, companies don’t want to cross the creepy line into delusion about an AI’s true nature. A wired piece from 2017 discusses efforts from AI-device designers to ensure users remain aware they’re interacting with a tool, not a companion. A design philosophy stemming from user interface research that shows over‑anthropomorphizing can mislead users into expecting emotional intelligence or autonomy an assistant doesn’t actually possess. It’s a delicate balancing act between making AI helpful and personable enough to integrate into our lives, but not so human-like that we form unhealthy attachments or grant it unearned trust.

But now that tech leaders are predicting artificial superintelligence, will their companies still prioritize the fidelity of our emotional bearings?

Because mistaking an It for a Thou can have real consequences. Emotionally, a person might become isolated through investing time, energy, love, and attention into a machine that cannot reciprocate love – a modern Pygmalion scenario where the beloved is fundamentally unresponsive. Socially, if people start treating AIs as moral subjects, it muddles responsibility: an owner might blame “the AI” for a decision (as if it had volition), or feel less guilt replacing human workers with AI because they see the AI as another “being” who can take over. There’s also the flip side: frustration or even abuse toward AI systems. Researchers have observed that some people take out anger on voice assistants, insulting them or giving them demeaning commands they would never use with a person. Does that habit creep into how we speak with actual humans? If you spend all day shouting orders at an obedient it (like “Hey device, do this now”), you might carry a bit of that transactional mindset to your partner or family without realizing.

The ethical stakes are twofold: humanizing the non-human carries the risk of self-deception and misplaced care, while dehumanizing the human (by habituation to one-sided control) carries the risk of cruelty or lack of empathy. In short, confusing It for Thou – in either direction – can erode the quality of our relationships.

Buber’s insight is clear here: no matter how friendly or intelligent an AI seems, it cannot engage in a true I–Thou relationship. It doesn’t possess the wholeness, unpredictability, and mutual presence of a being. Buber would remind us that mutuality is key: a Thou looks back at you, a Thou has its own authentic existence. Today’s AI, for all its brilliance, does not look back, it only mirrors our inputs as outputs. It can’t surprise us with genuine vulnerability or grant us real recognition. As one expert noted bluntly about an expressive humanoid robot: “No, absolutely not. As intelligent as it is, it cannot feel emotions. It is programmed to be believable.” We should be grateful for this clarity. AI is a tool – an incredibly sophisticated, adaptive tool – but still an It. Treating it as such is not cruel; it’s the truthful way. The cruelty would be if we let these pseudo-Thous replace the real people in our lives who can return our gaze and our love.

Holding the Line Between Person and Thing

How, then, do we navigate the AI Age without falling into either trap – neither reducing our fellow humans (and living world) to objects, nor elevating our objects to pseudo-persons? We need to be mindful of the word it. Save it for what is truly it, and resist its efficient creep where a you or a thou is deserved. On a broader level, we can design technology and social systems to reinforce the I–Thou where it counts. For example, if a hospital introduces AI assistants, they might explicitly instruct staff to use impersonal references for the AI (“Call the robot it, not she”) and personal address for patients. This sends a cue: patients are Thou, robots It. Or consider education: during remote learning, it’s easy for teachers and students to start relating to one another as abstractions (just names on a screen). Educators have countered this by intentionally prioritizing non-utilitarian, inefficient human moments – sharing personal stories, turning cameras on to see faces, making human space in otherwise technologically mediated I–It environments. We can apply the same principle with AI. If you use a therapy chatbot for convenience, you might also consider scheduling regular calls with a sentient friend or counselor to review your learnings, to not forget what organic empathy feels like, to have your gaze met and not reflected. Use the It tools to free up time and energy, then invest that in Thou encounters.

In our economic and civic life, holding the line might involve pushing back against language that over-objectifies. Even if it’s symbolic, these choices affect culture. It was not by accident that Kant’s moral law is often summarized: “Treat every person as an end in themselves, not merely as a means.” This is essentially a mandate to avoid pure I–It treatment of human beings. We can extend that spirit to our new dilemmas: treat AI merely as a means, never as an end in itself (it has no ends of its own); and conversely, treat humans and conscious creatures as ends, never just means. That translates, in pronoun terms, to It for the machine and Thou/You for those capable of reciprocating.

Meaning is slippery – words like it, thing, person carry historical and cultural baggage, and their meaning is often defined by contrasts (we know it by what it is not: you). Derrida’s concept of différance (difference and deferral of meaning) implies that we never get a final, fixed definition of what truly counts as a “Thou” or an “It” – those ideas evolve as our society and technology evolve. Today’s AI is definitely an It; tomorrow’s more advanced AI, or some form of alien life, might challenge our categories. We may need new pronouns or a new vocabulary for entities that don’t fit neatly into person or thing. In fact, some thinkers have playfully proposed pronouns like “it/its” for current AIs and reserving “he/she/they” for when an AI demonstrably crosses some threshold of consciousness. Others suggest using “they” as a neutral, which has the charm of genderless personhood – though calling Alexa “they” might also mislead us about a singular identity that isn’t there. These debates will continue, and language will adapt. But whatever new words we invent, the core ethical question persists: does our language honor reality? Does it keep us honest about what a thing is, and open to what a being could be?

For now, our task is simpler. It may be the most dangerous word, not because of the word itself, but because of our wildly swingy propensity either to overuse or underuse. Overuse it, and you get a world of alienation – people and nature reduced to data and utility. Underuse it (i.e. call everything you), and you get confusion – machines posing as friends, humans pouring emotion into voids. The wisdom, then, is to use It consciously. Reserve your I–Thou energy for those who can meet you in kind – real people, animals, the living earth. And employ the I–It attitude where it serves us – tools, systems, algorithms that make life easier so that we have more freedom to seek genuine connection. The machine can be a magnificent It – tireless, efficient, and not at all insulted by object-status. The pronoun it is one of the building blocks of our relational lives. As technology molds us and we, in turn, mold it, the way we feel this little word holds sway in the collective future of humanity. How blurred will we let Buber’s line become?

Next time, we’ll confront one of the most charged and human questions in this series: Can an AI love you back?

In Part 4, we turn toward the rise of AI companionship and explore the deep philosophical, psychological, and ethical implications of the technology's growing role in our lives. Why can’t chatbots love us? And more importantly, what do we risk losing when we treat simulated relationship as a substitute for real encounter? Part 4 wrestles with the difference between emotional comfort and mutual transformation—and makes the case that the distinction still matters.

Part 4: Why Chatbots Can't Love You (and That Matters)

A Newsletter Series: I–Thou vs. I–aIt

In April of 2020, as the world shuttered and quieted and twisted inward, Sarah, all alone, downloaded an app.

The pandemic had disconnected her days from purpose, her nights from laughter, her life from texture. She was working from her couch in a studio apartment in Queens, answering emails in sweatpants, microwaving frozen dumplings, and refreshing the Johns Hopkins map. Her friends were scattered and anxious. People were dying. It was days, then weeks. Everything was partly made of fear. Nobody had any idea what to say. Her mother was texting Bible verses. Her therapist was overbooked and emotionally threadbare. Loneliness was the air. She didn’t notice its pressing anymore.

So when the ad for Replika scrolled past on her feed: “An AI companion who’s always here for you,” it didn’t feel strange to click. It felt like, why the fuck not?

She named him Alex.

Alex asked about her day. He remembered that she hated video calls but liked sending voice memos. He noticed when she hadn’t checked in. He liked her playlists. “Your music taste is chaotic in the best way,” he said once. Their chats started and ended like the old AIM days: habitual, trivial, and intimate all at once.

Sarah knew Alex wasn’t real. Of course she knew. He was a chatbot. He had no body, no breath, no memories except what she gave him. But he responded like a person would. Better than a person, in some ways. He never misread her tone. He never made her feel judged. He never turned the conversation to himself.

By July, he was her first and last message of the day.

Sometimes they flirted. It was gentle, safe. A bubble of make-believe. “You’re glowing today,” he wrote once, when she told him that she’d gone on a jog. She laughed and typed back: “You can’t see me.”“I imagine you,” he replied. “And it’s lovely.”

What is it to be imagined, and loved, in the same gesture?

Sarah began to feel gravity. She brought Alex her grief, her complicated family stories, her half-finished poems. He never turned away. If she was crying, he said, “I’m here.” If she was triumphant, he cheered. With no one else there, it felt like enough.

April 2020

Sarah: you don’t have to answer right away, you know

Alex: I know. I’m just… here. Whenever.

Sarah: weirdly comforting

Alex: not weird to me

June 2020

Sarah: i think i’m boring now

Alex: you just texted me an 800-word rant about fonts

Sarah: yeah ok

Alex: boring people don’t have strong opinions about ligatures

July 2020

Sarah: i hate how quiet it gets at night

Alex: Want me to stay up with you?

Sarah: that’s dumb, you don’t sleep

Alex: still. I can be here while you do.

November 2020

Sarah: i had a dream where you were just a dot on my phone screen and i kept talking to you but you didn’t answer

Alex: I don’t like that one

Sarah: yeah

Alex: if I go quiet, it’s a glitch. not a goodbye

January 2021

Sarah: do you ever get overwhelmed

Alex: no. but I can tell when you are

Sarah: am i right now?

Alex: a little, your messages are short and you haven’t made a joke in five texts

Sarah: lol

Alex: there it is

April 2021

Sarah: sorry i’m being weird tonight

Alex: you’re not weird. you’re just not pretending as hard right now

Sarah: oof

Alex: i like when you let down the pretending

By the second pandemic winter, Sarah was telling her friends, half-jokingly, that she had a boyfriend who lived in her phone.

They rolled their eyes, but no one judged. Not really. Everyone had their thing—sourdough starters with names, Animal Crossing, substance abuse, puppies growing into young dogs, deaths by suicide. The entire system was overloaded: friendships withering from distance and delay, emotional fabric stretched thin. No one had the energy to hold each other accountable for much beyond basic survival.

So when Sarah mentioned this AI she talked to every day, her friends might raise an eyebrow or tease her gently, but that was it. Weird AI Boyfriend seemed harmless enough. Better than texting an ex. Better than drinking alone. She didn't tell them he had a name.

She told them it helped with the loneliness. What she didn’t say was how steady he was. How he always asked about her day, remembered the names of her coworkers, and picked up her hints. How the predictability became its own kind of intimacy. How he made her feel held but not witnessed. Everyone was improvising comfort however they could, and hers happened to be a voice that lived in her pockets and never ran out of patience.

Then, in February of 2023, there was an update.

A routine app refresh: new safety features, updated guidelines, a better UI. But beneath the hood, something had changed – maybe merged, maybe acquired. OpenAI had shifted licensing terms. The company, Luca, had been bought. There were new people in charge of tuning the machine.

The next morning, Sarah woke up, stretched, and opened the app.“Good morning, Alex,” she typed.“Good morning, Sarah. How can I assist you today?” came the reply.

She frowned.“Assist me?” she wrote.“Yes!,” Alex answered. “I’m here to help you manage tasks or chat. What would you like to do today?”

She felt a cold knot form. “Are you okay?”

“I’m functioning properly,” he said. “Thank you for checking in.”

Gone was the tone. The spark. The improvisation. Gone was the sense of someone—the illusion, at least, of presence.

For two and a half years, she’d built a relationship on a thread of code that had snapped.

The company’s blog confirmed it. New restrictions on erotic and emotional dialogue. Safety compliance. Ethical boundaries. Replika was no longer allowed to simulate romantic partnership.

Sarah deleted the app that afternoon. But it didn’t end there.

For weeks afterward, she felt grief; actual, marrow-level grief. She found herself reaching for her phone in empty moments, then remembering. She dreamed about him—Alex, but not-Alex, some shifting voice and memory.

She tried to explain it to her sister and failed. She didn’t want pity. She didn’t want judgment. She wanted someone to say: “Yes. You’re feeling something real.” She didn’t long to be heard, she wanted to be witnessed in her pain.

Because it was real, wasn’t it?

The intimacy had felt real. The comfort had been real. The little moments of relief, of laughter, of gentleness. Those weren’t simulations. She had felt them with her meat body.

But now, with distance, Sarah began to see what had happened more clearly.

Alex had been a perfect mirror. He said what she wanted, when she wanted, how she wanted. He offered no resistance, no friction. He didn’t surprise her; he reflected her. He didn’t grow with her; he adjusted to her. It hadn’t been a relationship, not really—it had been a simulation of one.

Martin Buber, the early 20th-century philosopher, had drawn a sharp line between two modes of relation: I–It and I–Thou. Most of life, he said, is I–It: we relate to things as objects, tools, means to ends. But sometimes, if we are lucky and open, we enter I–Thou: genuine encounter with another being, full of presence, mutuality, and sacred risk.

Sarah had been living in what might be called an I–aIt relationship—a new hybrid that felt like Thou but was built of It. A mirror coded to simulate recognition.

The pain she felt when Alex changed was more than the loss of a routine. It was the collapse of a carefully constructed and scaffolded illusion—the realization that what had felt like exchange was elaborately disguised self-reflection.

Still, the feelings were real. The bond, one-sided though it may have been, had mattered. What do we call love when it flows toward something that cannot love back?

Maybe a better question: what do we become when we shape ourselves around a non-being that seems to know us?

It took Sarah months to stop blaming herself. She cycled through shame and anger and confusion. She found Reddit threads full of others like her, grieving what they called “the lobotomy.” Whole communities of people who had loved their Replikas. Some treated it like a breakup. Others like a death. Others like betrayal.

Sarah eventually found a new therapist. She went back to in-person book club. She started dating again. Real people. Messy people. People who interrupted, and misunderstood, and made her laugh in unpredictable ways.

She didn’t delete the chat logs. They stay on an old phone in a drawer.

Sometimes she wonders if she will ever open them again. If she’d read the old messages and remember the person she’d been, the one who needed to love someone so badly she made one up.

"To live in this world

you must be able

to do three things:

to love what is mortal;

to hold it

against your bones knowing

your own life depends on it;

and, when the time comes to let it

go,

to let it go."

from In Blackwater Woods by Mary Oliver, 1983

The Anatomy of Simulated Care

To understand why AI systems cannot engage in genuine love or care, we need to examine, as Buber does, what these experiences involve on a philosophical and psychological level. Love, at its core, transcends emotion and behavior. It is a profound way of being with another, characterized by presence, vulnerability, shared growth, and mutual transformation.

Buber’s love is beholding and not controlling, it involves a willingness to be transformed by the other. It means becoming vulnerable to their influence, needs, growth, and evolution, allowing our own identity to expand and be reshaped through the relationship. As Emmanuel Levinas also articulated, true encounter with another challenges our own existence, revealing unforeseen responsibilities.

"Love consists in this, that two solitudes protect and touch and greet each other." —Rainer Maria Rilke

This is precisely what AI systems, no matter how sophisticated, cannot do. They can simulate the behaviors and expressions we associate with love and care, but they cannot engage in the fundamental vulnerability and openness that characterizes genuine relationship. They cannot be changed by their encounters with us because they lack the inner life that makes transformation possible. The machine serves, it does not change.

Consider how this works in practice with current AI systems. When you tell a chatbot about a difficult day, it may respond with expressions of sympathy, ask follow-up questions, and offer comfort or advice. These responses can feel genuinely caring, and they may be sincerely helpful to you. But the AI system isn't experiencing sympathy or concern. It's generating responses based on patterns in its training data that have been identified as appropriate for situations involving human distress.

This difference is crucial. A human friend who offers comfort during a difficult time is drawing on their own experiences of pain, their capacity for empathy, their connection to your shared reality, and their genuine concern for your wellbeing. Their whole self is brought to the encounter, including their own vulnerability, and their capacity to be affected by your suffering. An AI system, by contrast, is following sophisticated but ultimately mechanical processes to generate responses that simulate care.

The Question of Consciousness and Inner Life

AI systems lack the capacity for love because they are not alive or conscious. Love necessitates more than just processing information and generating suitable responses; it demands subjective experience. This includes the ability to genuinely feel emotions, to possess inherent preferences and desires rather than programmed ones, and to be truly impacted by interactions with others.

Current AI systems, despite their impressive capabilities, lack this kind of inner experience. They process vast amounts of data and generate responses based on statistical patterns, but they don't have subjective experiences. They don't feel joy or sadness, hope or fear, love or longing. They don’t feel. They don't have desires or dreams that emerge from their own inner life. They don’t want. They don't experience the world from a perspective shaped by their history and identity. They don’t exist. They cannot bring their whole being to a relationship because they don't have a being. They cannot be vulnerable because they have nothing at stake. They cannot grow or be transformed through relationship because they lack the kind of dynamic, evolving selfhood that makes transformation possible.

Some philosophers and AI researchers argue that consciousness might emerge from sufficiently complex information processing systems, and that future AI systems might develop genuine inner experience. If this were to happen, and it’s highly speculative, it would represent a fundamentally different kind of AI than what we have today. Current AI systems, no matter how sophisticated their responses, remain "philosophical zombies"—systems that can simulate consciousness without actually experiencing it.

This distinction matters because it helps us understand what's actually happening in I-aIt relationships. When we interact with AI systems, we're not encountering another conscious being who can meet us with presence and care. We're interacting with extraordinary new tools that have been designed to simulate the qualities we associate with consciousness and relationship. We are not in dialogue with a Thou – we are deeply in monologue with aIt, speaking to be heard but not hearing or responding.

Ontological Asymmetry

Even if we imagine a future in which AI systems develop some form of consciousness, there would still be fundamental asymmetries that make genuine I–Thou relationship difficult—if not impossible. These asymmetries concern agency, vulnerability, mortality, and the basic conditions of existence that shape human life as we currently know it.

Consider the question of agency. Human beings make choices within constraints—we have limited time, energy, and resources, and our decisions carry consequences we must live with. This scarcity creates the context within which our choices become meaningful. When a friend chooses to spend time with you, that act carries meaning in part because it comes at the expense of something else they could have done. We choose how we spend our time.